Overview

The concept of ‘justice’ is something that most people have an intuitive understanding of, even if they might have difficulty giving a precise definition to it. They might say justice is a desire to be treated fairly. Or perhaps they might argue that justice is the absence of discrimination. The idea is that people should be treated equally. There is an inherent feeling that a ‘just’ and equal society contributes to, or perhaps is even a prerequisite of, a ‘good society’. People often invoke the concept of justice when they feel an injustice has been committed, usually against them. If someone has had something stolen or been injured or otherwise harmed, they demand justice. If people feel they are personally discriminated against due to their race, gender, or sexual orientation, there are demands for social justice. If it is believed the system is inherently rigged against sections or classes of society, especially in terms of economic benefit, there are demands for distributive justice. If people believe that the state itself has been the source of injustice, especially when state-sponsored violence has occurred, there are demands for transitional justice. If pipelines rupture and desecrate fragile ecosystems, there are demands for environmental justice. If people believe there is systemic injustice at the international level, there are demands for global justice. Within these demands for ‘justice’, implicit claims are placed on both the offender and victim. There is an implied demand that the offender be punished and that the victim be compensated if that is possible.

Figure 1-1: Source Permission: CC-BY-SA-3.0 Courtesy of ChvhLR10.

Think of the image of Lady Justice: a woman, it hints at compassion; she is blindfolded, meaning justice should be impartial; she is holdings a set of scales meaning justice must be weighed; and finally, she holds a sword to indicate authority and punishment. Therefore, as citizens, it is important to consider questions of justice if we want to live in a ‘good society’. It means we have to assess our history critically. It means we have to critically examine how current political, economic, and social structures impact citizens. We need to question whether these structures have a differential impact on different segments of society. For example, Canada has crafted a narrative both at home and abroad for being an inclusive society and ‘good international citizen’. Domestically, it is argued Canada is a diverse country that celebrates multiculturalism. A country that has constitutionally entrenched fundamental rights and freedoms. Internationally, Canada is argued to be a good international citizen, the country that ‘invented’ modern peacekeeping, has fought to establish the ‘Responsibility to Protect’, and is generally an advocate for human rights. However, it is also the country that forced 150,000 Indigenous children into residential schools, with up to 6,000 of them dying in the process; that put 21,000 ethnic Japanese into internment camps during World War Two, 14,000 of whom were born in Canada; that consigned 254 Jews to die in the holocaust by denying the MS St Louis entry into Halifax. This tension is embodied in these two photos. The one on the left shows a Canada Day celebration with a Chinese Lion. A picture of inclusion and celebration of multiculturalism. The one on the right shows the men’s dormitory for interred Japanese Canadians in the Second World War. A picture of exclusion and fear of multiculturalism.

The majority of this course will be devoted to defining and operationalizing the concept of justice. However, this module will be devoted to looking at questions of justice in Canada, albeit without a clear definition of what ‘justice’ is. This will be used to set the back drop for the discussion in our subsequent modules.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to:

- Critically assess the dominant narrative of Canada

- Critique that narrative with historical examples of injustice in Canada

- Discuss contemporary issues of justice in Canada

- Take the Globe and Mail’s quiz “How well do you know Canada’s history?” https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/education/how-well-do-you-know-canada-history/article36157494/

- Watch Pierre Trudeau’s “Just Society” speech: https://youtu.be/xkmdLzYXcIM

- Watch “Why is Canada the most admired country in the World?” https://youtu.be/OHQ2lrAjKQk

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Watch David Suzuki “Japanese Internment Camps” https://youtu.be/C8TQTuMqM9g

- Watch the report by the National “Stolen Children: Residential School survivors speak out” https://youtu.be/vdR9HcmiXLA

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Watch “Mansbridge One on One: Cindy Blackstock” https://youtu.be/ahGQ0WBd0ng

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Canadian exceptionalism

- Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Chinese ‘head tax’

- City on the hill

- Diversity

- Famous Five

- Good society

- Indigenous

- Internment of Japanese Canadians

- Intersectionality

- Liberal Internationalism

- Maple washed

- Multiculturalism

- Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women

- Residential school system

Learning Material

Figure 1-4: ” Canada’s Coat of Arms” Source Permission: Fair Use. © 1994, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada

In order to engage in a critical examination of justice, we need to have some fodder for discussion. Something we can test our ideas on. For this class, we will use the backdrop of Canada to test our discussion of justice. This then begs the question, what is Canada? There is a dominant narrative that Canada is a country of diversity, multiculturalism, and peace. A country of nature and beauty. This narrative is rooted in a selected reading of history that emphasizes the arrival of European settlers, who established a nation that extended ‘A Mari usque ad Mare’; or to translate Canada’s official motto into English, ‘from sea to sea’. A nation that was carved out of a northern and inhospitable land. This is a story of the English, the French, and the Indigenous peoples through whom the state of Canada was established. It is the story of a country forged by grand projects like a national railway rather than revolution like the neighbours to the south. But it is not defined by pacifism. It includes the heroism and sacrifice displayed in Vimy Ridge or Passchendaele.

Figure 1-5: “Battle of Vimy Ridge” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Richard Jack.

It is also the story of a relatively young state playing a ‘good international citizen’ role in the world, ‘punching above its weight’ on issues of human rights and multilateralism. This has led to Canada being perceived as the 2nd best country in the world to live according to the 2017 U.S. News & World Report. At home, this narrative highlights the legal entrenchment of diversity and inclusivity achieved through the Constitution and most notably the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This part of the story highlights the achievements of same-sex marriage and women’s reproductive rights. And for all of this, people like former President Barack Obama argue that ‘the world needs more Canada’. But believing this narrative unquestionably ignores the darker side of Canadian history. If we are seeking to move ever closer to becoming a ‘good society’, we need to apply our ability to think critically. We need to confront issues of justice, and perhaps more importantly injustice, in our history and contemporary society. We need to ask questions about recognizing and addressing past wrongs. We need to ask questions of who is benefiting and who is not from contemporary political, economic, and social structures. We need to question the ‘maple washed’ history that is the dominant narrative taught in schools and portrayed in the media. This module will open this discussion by introducing the dominant narrative, looking at some historical examples that questions this narrative, and finally asks some questions of contemporary political, economic, and social structures in Canada.

- Take the Globe and Mail’s quiz “How well do you know Canada’s history?” https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/education/how-well-do-you-know-canada-history/article36157494/

- Post your score on the live poll app below

[yop_poll id=”1″]

Figure 1-6: “Sir John A. MacDonald” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of George Lancefield.

Figure 1-7: “Sir George Etienne Cartier” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of William Norman.

It was a process of building a nation via a railway and negotiations with the colonial metropole in London. There are tales of heroism at Vimy Ridge in the First World War, where the four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought as one for the first time. However, it was the Second World War where the modern narrative of Canada began to form. For the first time, the Canadian Government exercise foreign policy independence, declaring war on its own, a week after the UK and France had done so. The scale of the Canadian commitment to the war effort in material and manpower was foundational to the Canadian identity. Over a million men and women served in the war. That is almost one in ten with nearly 44,000 casualties. At the end of the war, Canada had the third-largest navy in the world and the fourth largest air force. Canadian diplomats were active if not determinative in the formation of post-war institutions, particularly the United Nations (UN) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Canadians fought in a UN force during the Korean War and exerted leadership in opposing French and British imperialism during the 1956 Suez Crisis.

Figure 1-8: “Canadian soldiers landing at Juno Beach on D-Day” Source Permission: Public Domain.

This would mark the start of the ‘golden era’ of Canadian foreign policy defined by Liberal Internationalism. This narrative includes the internalization of ‘Canada as a Peacekeeper’ role, opposition to Apartheid South Africa, and supporting international initiatives like the Anti-personnel Landmine ban, the creation of the International Criminal Court, and perhaps most notably the ‘Responsibility to Protect’. At home, the narrative of Canada was influenced by this internationalism. Canadians have struggled with processing the question of who ‘Canada’ is. The period between the 1960s and the 1980s was significant in Canadian identity building. In 1965, the Canadian flag as we know it became official, with the Maple Leaf becoming the country’s symbol. In the 1960s, the idea of multiculturalism gained currency and became official policy in 1971. Between 1960 and 1978, debates waxed and waned on bringing home the Constitution.

Figure 1-9: “Charter of Rights and Freedoms” Source Permission:CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Richard Foot.

The first referendum on Quebec sovereignty-association in 1980 created a window of opportunity for the Trudeau Government to patriate the Constitution with the addition of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Charter enshrines individual rights and freedoms of Canadians in the Supreme Court of Canada.

From this, a domestic narrative has evolved that Canada is a country of discussion, compromise, and consensus-building. Canada is posited to be a country where diversity is a strength, where people have hyphenated identities as English-Canadian, French-Canadian, Chinese-Canadian, Indo-Canadian, et cetera. Canada is described as a cultural mosaic juxtaposed with the American melting pot. What has taken hold is a form of Canadian exceptionalism, a narrative imbued of humble superiority, of smug politeness. This narrative is supported by evidence as demonstrated by the statistics compiled by Macleans magazine for the country’s sesquicentennial. In 2017, US News & World Report ranked Canada number one in terms of quality of life. Canada ranks 8th on the Global Peace Index. According to researchers at McMaster University, Canadian’s reputation for politeness holds true even in the most uncivil of formats, Twitter. According to the Legatum Prosperity Index, Canadians have the 2nd best access to individual freedoms. Canada scores relatively high on measures of social mobility, immigrant integration, and gender equality. Health care and other social services, while lagging behind some European states, positively shines when compared to the US. The Canadian primary education system consistently ranks in the top 10 in the world and was 4th in the last assessment in 2015. Moreover, according to the OECD, Canada ranks highly on the percentage of Canadians with advanced degrees. A Pew Research study argues Canada is the 3rd most LGBTQ-friendly country in the world. Vancouver, Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto all rank in the top 25 most liveable cities in the world according to the 2017 Mercer list. Further, the BBC has declared Toronto the most diverse city in the world. The OECD Better Life Index ranks Canadian air and water quality significantly better than comparative developed states. All of these statistics support a narrative of Canada as a ‘good society’ and hints at Canada being a ‘just society’.

Figure 1-10: “Go Canada!” Source Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Taylor McBride.

Watch Pierre Trudeau’s “Just Society” speech:

Watch “Why is Canada the most admired country in the World?”

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- How did Pierre Trudeau portray Canada in 1968?

- How is Canada seen today?

- How is this ‘Canada’s story’?

Figure 1-11: “Head Tax Receipt” Source Permission: Public Domain.

Another example is the Chinese ‘head tax’ instituted in 1885. Chinese nationals were singled out to pay, first, 50$, and then 100$, and finally 500$ for each person wanting to come to Canada. It was put in place to discourage Chinese immigration and specifically intended to slow family reunification for the more than 15,000 Chinese immigrants that had undertaken dangerous work on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway between 1881 and 1885.

We could also discuss the forcible relocation of three Inuit communities from Northern Quebec to the harsh climates of the high Arctic in 1953 and 1956, undertaken to strengthen Canada’s claims of Arctic sovereignty.

Figure 1-12: “High Arctic Relocation” Source Canada location map.svg:derivative work: Yug (talk)Canada (geolocalisation).svg: STyxderivative work: Elektryk4 (Canada location map.svg) Permission: CC BY-SA 2.5

Or there is the glaring fact that prior to 1929, women were not considered ‘persons’ under the law. It would take the advocacy of the ‘Famous Five’ to push the question through to the Privy Council in 1929 for women to be legally considered ‘persons’.

Figure 1-13: “A Statue of the ‘Famous Five'” Source Permission: Public Domain.

Another example is the indefinite imprisonment of Everett Klippert in 1965 as a ‘dangerous sex offender’ because he admitted to being gay. These, and many other examples, are all worthy of deep examination. However, we will look at two historical issues that question the overly rosy narrative of Canada: the residential school system and the internment of Japanese Canadians.

Figure 1-14: “Japanese Internment Camp, BC” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Jack Long.

In 1942, the Government of Prime Minister Mackenzie King enacted the War Measures Act, interring 22,000 ethnic Japanese, many of whom were born in Canada. The justification for this move was national security, ostensibly to avoid a potential ‘5th column’ in Canada’s war against Japan. Although it should be noted that all investigations into the reality of ‘enemies at home’ were found to be baseless. Some chose hard labour, building roads/railways or working on sugar beet farms. But the majority were relocated to government camps or abandoned mining towns in BC’s Slocan Valley. The camps to which they were sent were harsh, crowded, lacked basic necessities such as running water and electricity.

Adding insult to injury, the government confiscated their property and possessions in order to pay for their own internment. At the end of the War in 1945, the internees were given the choice of resettling outside of BC or signing up for voluntary repatriation to Japan without restitution for seized assets. Most chose to move east but Ottawa did begin the process of involuntarily deporting up to 10,000 Japanese Canadians. In the face of domestic opposition, PM Mackenzie King did relent but upwards of 4,000 people were sent back to Japan. It wasn’t until 1949 that Japanese Canadians were allowed to return to the West Coast. In the 1960s, the attitude of the Government of Canada began to shift. Prime Minister St Laurent had stated in 1961 that the forcible internment of the Japanese was the right decision.

Figure 1-15: PM Lester B. Pearson” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Start Newspaper MIKAN No. 3607934.

However, by 1964, Prime Minister Pearson would argue this was a black mark against Canada’s principled position and tradition of supporting human rights.

Finally, in 1988 the Mulroney Government offered the surviving individuals affected by the internment an official apology and 21,000$. This Japanese internment affair was a product of an officially sanctioned anti-Asian racism, rooted most deeply in BC but prevalent in Canadian society. In sentiments that echo some contemporary global immigration debates, the white settler population in Canada saw Asian immigration as a threat to their jobs and quality of life. Asians were denied access to unions and were forced to take less desirable jobs for less pay. They were denied the right to vote, the right to hold public office, and the right to work as public servants. In 1887 and 1907, Asian neighbourhoods in Vancouver were subject to violent anti-Asian riots.

Figure 1-16: “Damage done by the Asiatic Exclusion League in Vancouver 1907” Source Permission: Public Domain.

Various restrictive anti-Asian immigration policies had been imposed such as the previously mentioned ‘head tax’ imposed to curb immigration from China in 1885 or the 1907 Order-in-Council which banned Indian immigrants. An informal agreement was reached with the Japanese government to slow immigration in 1907 as well. Restrictions against Asians began to wane at the end of the 1940s with Chinese and South Asian Canadians gaining the right to vote in 1947 and Japanese Canadians in 1949. However, while legal obstacles might have been removed, more informal obstacles have remained and are far more difficult to overcome. For example, polling in 1994 indicated a majority of Canadians believed immigration was too high, specifically identifying visible minorities including Asians. In 2017 polls indicate 26% of Canadians still believe immigration levels are too high. Before applying this history to a discussion of Canada as a ‘good’ or ‘just’ country, let us look at one more example, the history of the residential school system.

Residential schools were a product of collaboration between Christian churches and the Canadian government. Their purpose was to assimilate Indigenous children into the European settler culture. While the earliest schools were established by the Récollets and later the Jesuits in New France between 1620 and 1680, these early efforts were largely unsuccessful due to the enduring autonomy of First Nations. However, beginning in the 1830s, Roman Catholic, Methodist, and Anglican residential schools became more firmly entrenched. Following Confederation in 1867 and the implementation of the Indian Act, the education of Indigenous children became a responsibility of the Federal Government. Many First Nations initially welcomed access to this European education as a means to provide their children with greater opportunity in the increasingly settler-dominated economy. While these Christian-run schools did work with the government to provide some economic-based skills, they also, and many argue primarily, sought to convert Indigenous children and aggressively assimilate them into Canadian society. It was believed that children were more receptive to such assimilation than adults. The residential school system began in earnest in 1883 with the establishment of three industrial schools in the prairies.

Figure 1-17: “Qu’Appelle Indian Industrial School in Lebret, 1885” Source Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 1-18: “Indian Residential School in the Northwest Territories” Source Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

At the height of the program in the 1930s, there were over 80 residential schools, primarily located in the western provinces and territories but also in northern Ontario and Québec. In total, there were 130 schools in every province and territory with the exception of Newfoundland, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. These schools were church-run, government-funded, and focused on an industrial education – not quite what the First Nations had envisaged in the 1870s.

As many Indigenous children did not live in communities with access to day schools, they were forced to live in boarding or residential schools. Students at these schools had few opportunities to return home. Communication with family back home was strictly conducted in English even though most family members couldn’t read. Most students lived at the school for 10 months of the year and some lived there all year. Life at these residential schools was harsh. The practice of Indigenous traditions and language was strongly discouraged. Punishment for disobeying the rules was severe. Living conditions were abysmal, food sub-standard, clothing inadequate, and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse were common. Moreover, in a few cases, it has been documented Indigenous children were used for experimentation, like nutritional experiments performed on malnourished Indigenous children in the 1940s and 50s without parental consent. Many children resisted assimilation, refusing to cooperate with authority figures, and many others tried to run away. In total, approximately 150,000 children went through the residential school system and many died. The number of deaths attributed to disease due to malnourishment, from abuse as well as from exposure to the elements when trying to run away is impossible to count. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission documented 3,200 deaths but the head of the commission, Justice Murray Sinclair, argues it is more likely closer to 6,000 and perhaps much more. This maltreatment and these deaths pose a striking condemnation of the residential school system. But perhaps its most pernicious influence has been how the residential school system broke familial bonds, contributing to intergenerational trauma. Children grew up without knowing their traditions, without pride in themselves and in their people. Parents lived with forced separation from their children and the implication that they were unfit to raise them. Residential school survivors often lacked the role models of what it meant to be a father, mother, brother, or sister. This absence of traditional structures and role models in combination with abuse and internalization of shame has severely undermined the ability to heal in many communities. This in turn has contributed to the intergenerational impact of residential schools. In the next section, we will look at contemporary issues with the Canadian narrative, including some of which have been a result of such intergenerational trauma.

Watch David Suzuki “Japanese Internment Camps”

Watch the report by the National “Stolen Children: Residential School survivors speak out”

*Warning the language and stories may be disturbing to some

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- In your own words, what happened in the case of Japanese internment?

- In your own words, what happened in the case of the residential school system?

- How do these two events provide a different perspective on the narrative of Canadian society?

In section one of this module, we looked at the crafted narrative of Canada. In section two we looked at two prominent historical examples which question this narrative. In trying to reconcile these two narratives, some have argued that the darker aspects of Canada’s past are just that – the past. That while we need to recognize and address past wrongs, this is now the country of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, of diversity, and inclusion. That racism and inequality do exist, but that these are not the dominant values of the majority of contemporary Canadians. In this section, we will assess indicators of equality in contemporary Canadian society. At the broadest level, equality can be measured by the distribution of wealth in society. Since the 1980s, income inequality has risen in Canada. The two richest billionaires now control more wealth than the bottom 30% of Canadians, roughly 33 billion dollars. The richest thirty-three men in Canada own 112 billion dollars. Between 1988 and 2011, the poorest 10% of Canadians only saw their average incomes increase by 65$. The average increase of the top 1% on the other hand has been 11,800$.

However, these measures of inequality do not tell the whole story since inequality impacts different segments of society in different ways. In Canada, it matters if you are white or a person of colour, a man or a woman, or even the city/province where you were born. Let us take gender for example. Canada may have a gender-balanced cabinet because, as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau argued, “it’s 2015”.

But all of those 33 richest Canadians are men. In the workplace, women still face significant barriers to equity. Full-time working women’s yearly earnings are 74.2 cents for every dollar made by full-time working men. When accounting for differentials in working hours, that gap is still 87.9 cents for every dollar made by men.

Figure 1-20: “OECD gender wage gap” Source Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Delphi234.

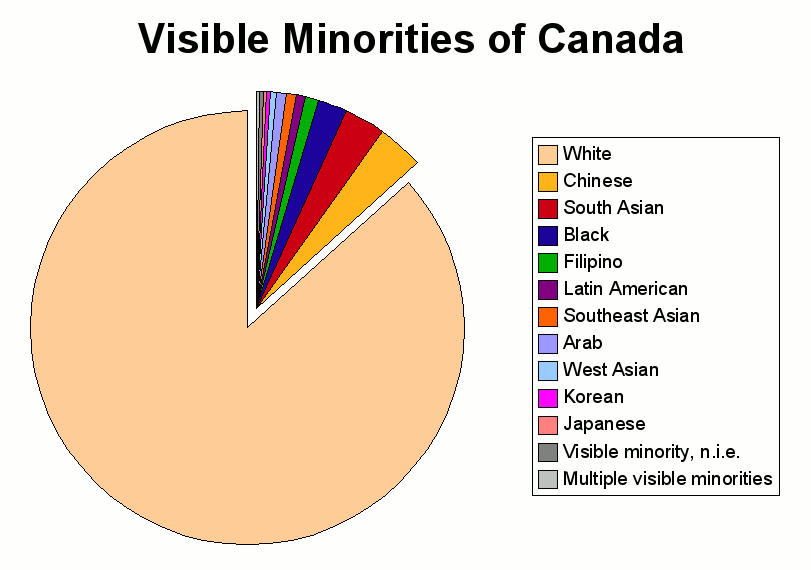

A glass ceiling between middle management and upper management is still apparent in Canada with only 12% of women holding seats on TSX-listed companies. Further, only 29% of these companies have at least one female director. Inaccessible child care exacerbates the problem since women are disproportionately responsible for child-rearing. Other societal measurements also highlight gender inequality. In terms of political representation, 2015 was a record for Canada with 88 women being elected to Parliament. But this still only represents 26% of total seats. Women are also more susceptible to gender-based violence with women accounting for 56% of all violent victimization and young women are 1.9 times more likely to be victimized than young men. Beyond gender, another vector of inequality is geography. If you are born in central AB, southern SK, southwestern ONT, or urban centers like Vancouver, Calgary, and Toronto, it is statistically probable you will exceed the income of your parents. Whereas, if you are born in places like MB, excluding Winnipeg, coastal BC, and more remote communities it is more likely you will fail to do so. Another indicator of inequality is ethnicity and especially being a visible minority. In 2016, 22% of Canadians identified as being a visible minority. The total income of visible minorities is on average 26% lower than non-visible minorities. The situation is more problematic for recent immigrants who make on average 37% less. According to an Ipsos poll in 2017, 25% of Canadians say they experienced racism which is an 8% increase since 2005. However, the same poll shows that more Canadians believe that racism is less of a systemic problem.

Figure 1-21: “Visible Minorities in Canada” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0

The juxtaposition between these two data points, to a degree, highlights the disconnect between how the majority of Canadians understand the national narrative and the prevalence of inequality and injustice in Canada.

However, the most damning statistics pertain to the quality of life for the Indigenous peoples in Canada. For example, Indigenous peoples in Canada earn 60% of the national average median income. Compared to the national average, Indigenous people are: 2.1 times more likely to be unemployed; 6.1 times more likely to be murdered; 10 timed more likely to be incarcerated; 2.7 times more likely to drop out of school. Infant mortality rates are 2.3 times the national average. However, perhaps, the most disheartening statistics surround the suicide rate in First Nations communities. Suicide and self-inflicted injury is the number one cause of death for First Nation’s people under the age of 44. In 2016, on the Attawapiskat First Nation Reserve, 11 people tried to commit suicide in one night. This was on top of the 100 attempts made over the previous 10 months. And Attawapiskat is neither unique nor alone. In the Pimicikamak Cree Nation community in northern Manitoba, six people had committed suicide over 3 months and more than 150 were on suicide watch. On the whole, young indigenous men are 10 times more likely to commit suicide than their non-indigenous counterparts and for young indigenous women, it is a staggering 21 times more likely.

Figure 1-22: “MMIWG sign” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Cory Doctorow.

This last statistic highlights the importance of intersectionality. As discussed earlier, gender is a vector of inequality for all Canadians. But it is even more prevalent if you are female and a person of colour. For example, take the statistics surrounding the case of Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women. Between 1980 and 2012, nearly 1200 women and girls have been officially identified as murdered or missing. Indigenous women’s groups place this number at over 4000. Indigenous women are 3.5 times more likely to be victims of violence and their homicide rate is 7 times the rate of non-indigenous women. Indigenous women also face higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and access to social services. These statistics are deeply tragic. Explanations that seek to understand such tragedy point to issues of racism, underfunding of First Nation schools, health and public services, as well as the condition of so many First Nation reserves. For example, when the Guardian newspaper interviewed a 16-year-old Indigenous girl named Katrina, she said she has contemplated suicide. She spoke of the stigma attached to being aboriginal, that people called her a ‘freeloader’ and a ‘dirty Indian’. She felt she was being judged for being Indigenous. In terms of the underfunding of education and social services, it is argued such practices have created a fertile environment for the tragic outcomes discussed above. For example, TD Bank argues the government has under-funded on-reserve education, where they only get 70 cents for every dollar spent on non-indigenous schools. This has resulted in on-reserve high schools lagging an average of two grades compared to their urban counterparts. Similarly, government reports have recognized chronic underfunding for on-reserve social services and health care. Without comparable investment in education, health care, and social services, how are First Nation children expected to overcome barriers to success that are on average much more significant than faced by non-indigenous children? Take, for example, the reserves themselves with many in desperate conditions. More than 100 First Nation reserves lack appropriate housing, electricity, or running water. Of these communities, 90% are on a boil water advisory. These statistics mean that a large proportion of Indigenous people are living in conditions of abject poverty. The question is, how can these statistics be reconciled, if at all, with the narrative of Canada as a ‘good’ and ‘just’ society?

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- Who is Dr Cindy Blackstock?

- What is she campaigning for?

- Why does she argue we are born in racism?

- What are the practical implications of underfunding of First Nations?

- What does Dr Blackstock argue is needed to address issues of racism in Canada?

- What are the two Canada’s that Dr Blackstock identifies?

- What is at stake in this debate?

This course seeks to explore issues of justice and injustice in politics and law. In order to do this in a meaningful way, we need to think deeply about the practical implications of these issues. One means to do this is to look at what is happening here in Canada. To this end, this module has introduced three different ways to look at Canadian society and whether Canada is a ‘good society’ and a ‘just society’. The dominant narrative is of ‘Canadian exceptionalism’, of this being a country of diversity and inclusion. That this is a model to be emulated. However, historical examples of Canada’s residential school system or of Japanese internment camps suggest a counter-narrative that questions this position. When we look at contemporary statistics on life in Canada, more questions are raised. These statistics raise questions of income inequality, gender inequality, and most tragically, the state of life for many Indigenous peoples living in Canada. All three sections of this module tell ‘a’ truth. There is truth for some Canadians that this is an exceptional country that has done exceptional things. There is also truth in that there are deeply troubling aspects to Canadian history. And there is also truth in the argument that the dominant narrative of Canadian exceptionalism is not being experienced equally by all the peoples in Canada. As we go forward in this course, these questions will provide a tangible backdrop to discuss ‘what is justice’ and ‘what is injustice’ in politics and law.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Canadian exceptionalism: is a term which is plays on the more commonly known ‘American exceptionalism’. It posits that Canada is a liberal, multicultural country that is defined by diversity, inclusivity, peace.

Charter of Rights and Freedoms: forms part of the Constitution Act, 1982. It guarantees political and civil rights to Canadian citizens. As part of the constitution, the Charter is interpreted and defended by the Supreme Court of Canada empowering judicial review.

Chinese ‘head tax’: is a fixed fee applied to all Chinese people trying to enter Canada. It was created under the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 and was meant to curb family reunification of the 15,000 Chinese labourers brought in to work on the railway.

‘City on the hill’: is a reference to the liberal position of being a model for others to emulate.

Diversity: the political and/or social policy of accepting people of different backgrounds, including ethnicity, sexual orientation, or religious background

Famous Five: refers to five Albertan women, namely: Emily Murphy, Irene Marryat Parlby, Nellie Mooney McClung, Louise Crummy McKinney and Henrietta Muir Edwards. They sought and succeeded in having women legally considered persons under the law.

Good society: is defined by a societal conversation around what is important, what is valued, and what is just/unjust. It means asking hard about the society we want to live in.

Indigenous: refers to ethnic groups who are the original inhabitants of any given territory. The term often stands in contrast to people who have occupied or colonized a given territory.

Internment of Japanese Canadians: is the process by which the Canadian government forcibly removed upwards of 21,000 Japanese Canadians from the West Coast during the Second World War. Some chose hard labour, building roads/railways and working on sugar beet farms. But the majority were relocated to government camps or abandoned mining towns in BC’s Slocan Valley. The camps to which they were sent to were harsh, crowded, lacked basic necessities such as running water and electricity.

Intersectionality: identifies how systems of power are interconnected and often impacts those who are most marginalized in society. Intersectionality assess how different categories such as class, race, sexual orientation, disability and gender form mutually reinforcing structures.

Liberal Internationalism: refers to a foreign policy orientation defined by interventionist policies in support of liberal objectives. These policies can take the form of humanitarian aid, institutional cooperation, or the use of military force.

Maple washed: refers to an idealized version of Canadian history that ignores those actions and decisions that may tarnish that idealized narrative.

Multiculturalism: defines a policy or entity which either recognizes or promotes the co-existence of multiple ethnicities. At a minimum it advocates for respect for different cultures and more robust versions promote or entrenches cultural diversity.

Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women: is the recognition that Canadian indigenous women are disproportionately affected by violence and are more likely to become homicide victims than non-indigenous women.

Residential school system: were Christian run schools, funded by the government to provide Indigenous children economic skills, convert them to Christianity and aggressively assimilate them into Canadian society.

References

Barrera, Jorge. “Health Canada knew of massive gaps in First Nations child health care, documents show” CBC. Accessed March 11, 2018 http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/health-canada-ruling-children-1.4368393

Brysk, Alison. Global Good Samaritans : Human Rights as Foreign Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Carlson, Kathryn Blaze. 11 January 2011, “'None is too many': Memorial for Jews turned away from Canada in 1939” The National Post. Accessed March 11, 2018 http://nationalpost.com/news/none-is-too-many-memorial-for-jews-turned-away-from-canada

CBC News. 16 March 2008 “A history of residential schools in Canada” CBC Accessed March 11, 2018. www.cbc.ca/news/canada/a-history-of-residential-schools-in-canada-1.702280

CBC News. 30 July 2013. “Aboriginal nutritional experiments had Ottawa’s Approval” CBC. Accessed March 11, 2018 http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/aboriginal-nutritional-experiments-had-ottawa-s-approval-1.1404390

Cheung, Helen Kwan Yee. "Righting Canada’s Wrongs: The Chinese Head Tax and Anti-Chinese Immigration Policies in the Twentieth Century by A. Chan." The Deakin Review of Children's Literature 5, no. 1 (2015): The Deakin Review of Children's Literature, 07/21/2015, Vol.5(1).

Ciolfe, Terra. 7 July 2017. “The world things the world needs more Canada, too” Macleans. Accessed March 11, 2018 http://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/the-world-thinks-the-world-needs-more-canada-too/

Grant, Tavia. 12 November 2017. “Gender pay gap a persistent problem in Canada: Statscan data” The Globe and Mail. Accessed March 11, 2018. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/gender-pay-gap-a-persistent-issue-in-canada/article34210790/

Hickman, Pamela M., and Fukawa, Masako. Righting Canada's Wrongs : Japanese Canadian Internment in the Second World War. Toronto: James Lorimer and, 2011.

Hutchins, Hope (February 2013). “Measuring violence against women: Statistical trends: Section 2: Risk factors for violence against women.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2013001/article/11766/11766-2-eng.htm#a20

IPSOS. 2017. “Dangerous World 2017” IPSOS. Accessed March 11, 2018 https://www.ipsos.com/en/dangerous-world-2017

Jackson, Andrew. 8 April 2015. “The Return of the Gilded Age: Consequences, Causes and Solutions” The Broadbent Institute. Accessed March 11, 2018 https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/broadbent/pages/3987/attachments/original/1431376127/The_Return_of_the_Gilded_Age.pdf?1431376127

Jedwab, Jack. “Canada Lacks A Definite Narrative About Who Founded The Country” The Huffington Post. Accessed March 11, 2018 http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/jack-jedwab/canada-founding-narrative_b_10798992.html

McCavitt, Candice M., Opotow, Susan, Moghaddam, Fathali, and Dean, David. "Eugenics and Human Rights in Canada: The Alberta Sexual Sterilization Act of 1928." Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 19, no. 4 (2013): 362-66.

McPhillips, Deidre. 3 March 2017, “Why Canada’s the No. 2 Best Country, Again” US News and World Report. Accessed March 11, 2018 https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2017-03-24/why-canadas-the-no-2-best-country-again

Millar, Nancy. The Famous Five : A Pivotal Moment in Canadian Women's History. Calgary: Deadwood Pub., 2003.

Monsebraaten, Laurie. “Income gap persists for recent immigrants, visible minorities and Indigenous Canadians” The Star Accessed March 11, 2018 https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2017/10/25/income-gap-persists-for-recent-immigrants-visible-minorities-and-indigenous-canadians.html

Obama, Barak. June 29 2016. “Obama: The world needs more Canada” CBC http://www.cbc.ca/news/obama-the-world-needs-more-canada-1.3659172

Oxfam. 15 January 2017. “Just 8 men own same wealth as half the world, says new Oxfam report” Oxfam Canada. Accessed March 11, 2018 https://www.oxfam.ca/news/just-8-men-own-same-wealth-as-half-the-world-says-new-oxfam-report

Porter, Jody. “First Nations students get 30 per cent less funding than other children, economist says” CBC. Accessed March 11, 2018 www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/first-nations-education-funding-gap-1.3487822

Puxley, Chinta. 31 May 2015. “Up to 6,000 children died at Canada’s residential schools, report finds” Global News. Accessed March 11, 2018 https://globalnews.ca/news/2027587/deaths-at-canadas-indian-residential-schools-need-more-study-commission/

Racco, Marilisa. 5 July 2017. “Gender equality in Canada: Where do we stand today?” Global News. Accessed March 11, 2018 https://globalnews.ca/news/3574060/gender-equality-in-canada-where-do-we-stand-today/

Randhawa, Selena. “'Our society is broken': what can stop Canada's First Nations suicide epidemic?” The Guardian Accessed March 11, 2018 https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/aug/30/our-society-is-broken-what-can-stop-canadas-first-nations-suicide-epidemic

Schwartz, Daniel. 2 June 2015, “Truth and Reconciliation Commission: By the numbers” CBC. Accessed March 11, 2018. http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/truth-and-reconciliation-commission-by-the-numbers-1.3096185

Saunders, Doug. 23 June 2017. “A tale of two Canadas: Where you grew up affects your income in adulthood” The Globe and Mail. Accessed March 11, 2018 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/a-tale-of-two-canadas-where-you-grow-up-affects-your-adult-income/article35444594/

Savage, Luke. “Accounting for Histories: 150 Years of Canadian Maple Washing” OpenCanada Accessed March 11, 2018 https://www.opencanada.org/features/accounting-histories-150-years-canadian-maple-washing/

Schwartz, Daniel. 17 April 2012, “6 big changes the Charter of Rights has brought” CBC. Accessed March 11, 2018 http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/6-big-changes-the-charter-of-rights-has-brought-1.1244758

Toronto Star. "Editorial Exchange: Trudeau Is Right to Pardon Everett Klippert, Canada's Iconic Gay Offender." The Canadian Press (Toronto), March 02, 2016.

Zilio, Michelle. 10 April 2017 “Two richest Canadians own more than bottom 30% of population, report finds” The Globe and Mail. Accessed March 11, 2018 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/report-makes-recommendations-to-achieve-economy-that-works-for-all-canadians/article33629405/

Supplementary Resources

- Eshet, Dan., Theodore Fontaine, and Canadian Electronic Library. Stolen Lives : The Indigenous Peoples of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools. DesLibris. Documents Collection. 2015.

- Hickman, Pamela M., and Fukawa, Masako. Righting Canada's Wrongs : Japanese Canadian Internment in the Second World War. Toronto: James Lorimer and, 2011.

- Lammam, Charles., and Canadian Electronic Library. Towards a Better Understanding of Income Inequality in Canada. Documents Collection. 2017.

- Resnick, Philip. The European Roots of Canadian Identity. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2005.