Overview

In Module One we discussed the concept of justice and how it is invoked in a variety of ways. It is most often used to underscore a particular grievance, from sexual discrimination to tax fairness. We also discussed the connection between justice, the idea of a ‘good society’, and what that means both in Canada and abroad. In Module Two we introduced some of the dominant narratives of justice, including the welfare, freedom, and justice models. In this Module, we will be taking a closer look at a subset of the welfare model, utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism emerged in the context of the tail end of the enlightenment period and the rise of the industrial revolution. This is important as the enlightenment had privileged reason and rationality and the Industrial Revolution was in the process of fundamentally reorganizing how we live, work, and organize our social relations. In this mix, some believed a more scientific and rational means to judge social policy was needed. For early advocates, utilitarianism was seen to be a system of secular morality and therefore represented a solution to the problem of adjudicating moral dilemmas in the absence of an agreed upon religious base. Such a system still holds great appeal in our contemporary world and especially in a multicultural state like Canada. Utilitarianism provides a means to judge policy and action without reference to specific value systems, absolute rules, or in accordance to with defined duties. It does so by positing a policy or action as moral or ‘just’ if it provides the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. This seems like a common-sense approach to policy and action – produce happiness and reduce unhappiness. However, as we also saw in Module Two, there are problems with this approach. How is happiness to be quantified? How are different types and degrees of happiness to be compared? And perhaps most problematic, does the happiness of the majority outweigh the rights of minorities? This module will explore the idea of utilitarianism, its application to questions of justice, and some of the issues that emerge from such an application.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the utilitarian position of Jeremy Bentham

- Describe the utilitarian position of John Stuart Mill

- Apply both Bentham’s and Mill’s utilitarianism to questions of justice

- Read Chapter 2 in Michael Sandel’s Justice

- Read the Guardian Post, ‘How Utilitarian Are You?’: How utilitarian are you? Personality quiz | Life and style | The Guardian

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Watch ‘Law and Justice – Utilitarianism’ Jeremy Bentham: https://youtu.be/dyhGC69kVC8

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Watch ‘Law and Justice – Utilitarianism’ John Stuart Mill: https://youtu.be/uv6GT3MeoRc

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Watch: https://youtu.be/k5g9AlCQFaM

- Read: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/what-would-john-stuart-mill-think-about-todays-campus-free-speechdebates/article38005374/

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Certainty

- Consequentialist

- Cost/benefit analysis

- Duration

- Empiricism

- Enlightenment period

- Extent

- Faithfulness

- Fecundity

- Higher pleasures

- Impartiality

- Individual liberty

- Industrial revolution

- Intensity

- Just-desserts

- Legal rights

- Lower pleasures

- Moral rights

- Pig philosophy

- Propinquity

- Purity

- Qualitative

- Quantitative

- Rationality

- Relativist

- Teleological

- Utilitarianism

- Utility calculus

Michael Sandel, Justice “The Greatest Happiness Principle/Utilitarianism” pg.31-59 [Textbook]

Learning Material

From a utilitarian perspective, the answer is yes, torture the terrorist if the consequences of doing so could save the many lives in that city. This is because advocates of utilitarianism are not hampered by religious commandments nor an absolute concept of human rights. From a utilitarian perspective, we judge a policy or action as good, or for the purposes of our course ‘just’, by its consequences. This is done by undertaking some form of cost/benefit analysis or utility calculation.

Figure 3-3: “Jeremy Bentham” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Jeremy Bentham.

For the founder of utilitarianism, Jeremy Bentham, consequences should be measured using a cost-benefit analysis based on pleasure and pain. In the example above, the pain inflicted on the terrorist by being tortured is measured against the pleasure generated for the many who would avoid being murdered and maimed by the WMD. Therefore, torturing the terrorist is ethical and just.

With utilitarianism, Bentham was trying to make ethics a science, a means to quantitatively determine what the right course of action should be. As we will see, there are substantial critiques of Bentham and especially the hedonistic basis of his utility calculation. One critique is the problem of comparing forms of pleasure. Bentham does not judge between particular types of pleasure, only on the quantitative amount of pleasure attained. In fact, reducing different types of pleasure to measurable quantitative units is central to his purpose: creating a scientific method to adjudicate the ethics of a policy or action. This means that if people have a choice between two actions, there is no distinction made between something that is considered to be base and something that is considered to worthy. Thus determining which is better, the antics of Johnny Knoxville on ‘Jackass’ or watching Neil deGrasse Tyson explore our world and universe in ‘Cosmos’, is a function of much pleasure each produces.

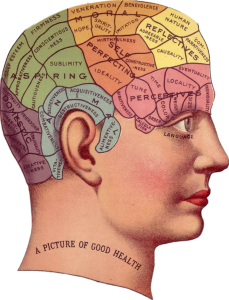

Figure 3-4: Source Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 3-5: Source Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

Figure 3-6: “John Stuart Mill” Source Permission: Domain. Courtesy of Steroscopic Company.

Another criticism is the possibility that minority rights may be sacrificed in order to satiate the pleasure of the majority, for example, the Burqa and Niqab controversy we discussed in Module Two. If the majority gain more pleasure from a ban on Niqabs and Burqas than the pain suffered by Muslims who feel ostracized, then the policy is good, moral, and just.

In an attempt to address these critiques, John Stuart Mill introduces a qualitative dimension to Bentham’s quantitative utilitarianism by differentiating between forms of pleasure.

Mill makes a distinction between higher pleasures and lower pleasures. He argues that higher-level pleasures are intellectual, and that true happiness requires the attainment of such pleasures. Thus it is possible to argue that ‘Cosmos’ is a higher-order pleasure than ‘Jackass’ and that the religious rights of Muslims are a higher-order pleasure than the prejudicial pleasure of the majority. This does seem to have merit and goes some way to addressing Bentham’s critiques. However, there are also substantial critiques of Mill’s utilitarianism, especially the increasing prescriptiveness of his arguments and the weakening of the democratic and universal basis of Bentham’s utilitarianism. There are lots of interesting applications of both Bentham’s and Mill’s thoughts to contemporary political questions. But we are going to focus on one – to what degree does utilitarianism offer insight into questions of justice? In the following module we are going to look first at Bentham’s and then Mill’s variants of utilitarianism, followed by a discussion of what it means to our discussion of justice.

Before moving on, let us assess how utilitarian you are.

-

- Read the Guardian Post ‘How Utilitarian Are You?’: How utilitarian are you? Personality quiz | Life and style | The Guardian

- Based on the results, post one sentence below as to why you chose A, B, C, D.

Figure 3-7: “Cost Benefit Analysis” Source CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Nick Youngson.

Utilitarian thought abounds in our modern world. When companies or the state undertake cost-benefit analysis, they are using a utilitarian logic.

The idea is to reduce variables to some common measurement like currency or welfare in order to make a decision. If the pros outweigh the cons, the actor should undertake the action or pursue the policy. If the cons outweigh the pros, then the action or policy should be abandoned. When we are discussing whether to expand pipelines or introduce a comprehensive pharma-care plan, the government uses a cost-benefit analysis. Take the pipeline argument for example. If the potential economic and employment benefits of a pipeline outweigh the potential capital, environmental, and political costs, then the government should approve it. On the face of it, this is a common-sense approach to solving tough problems. However, there are issues with how to reduce variables like the environment or political costs to a common measurement. This is where Bentham comes into the picture as he sought to find a quantitative means to adjudicate what is right, good, and just.

The result of his enquiry is utilitarianism: a consequentialist, relativist, and teleological ethic. It is consequentialist in that a policy or action is determined to be ethical if the outcomes are ‘good’. It is relativist in that context is paramount and there are no universal rules or commandments that must be followed regardless of the outcomes generated. It is teleological in that has telos or purpose – to maximize utility. For Bentham, utility is reduced to happiness defined by pleasure and the absence of unhappiness defined by pain.

Figure 3-9: “Epicurus” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of interstate295revisited.

He believed all important decisions could be reduced to a cost-benefit analysis based on these principles.

So where did he get his ideas and how would he seek to reduce everything down to a single measurement?

While utilitarianism can be traced back to the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus, it was Bentham who introduced it to the modern era. Bentham was living through two great transformations: the 18th-century enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. The Enlightenment stressed reason, rationality, empiricism, individual liberty and the use of scientific thought to solve problems, especially problems of governance.

Figure 3-10: “Salon de Madame Geoffrey” Source Public Domain.

Figure 3-11: “Hartmann Maschinenhalle 1868” Source Permission: Public Domain.

The Industrial Revolution was fundamentally reorganizing how we live, work, and organize our social relations.

In this period of transformation, traditional sources of authority and governance were being challenged and new means were being sought to decide what actions or policies were good, right, and just. Bentham argued for utilitarianism as a system of secular morality that was appropriate for liberal and/or pluralistic societies. Rather than judge policy or action on the basis of religious doctrine, natural law, or innate knowledge, decisions should be based on the benefit accrued to the majority: the goal should be to provide the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. It is important to note that in this utility calculus Bentham doesn’t distinguish between the rich and poor nor between men and women. All should count equally. And each decision should be judged individually. So how is such a calculation to be undertaken? Bentham believed that humans are governed by two impulses, to embrace pleasure and avoid pain. Further, he posited that these two impulses could be quantified, with happiness being calculated as pleasure minus pain. Bentham believed units of pleasure and pain could be derived from seven measurements:

- Duration or how long a pleasure will last

- Fecundity or how likely a pleasure is to provide further pleasure

- Purity or how likely will the pleasure not be followed by pain

- Propinquity or how soon the pleasure will occur

- Intensity or how strong the pleasure will be

- Certainty or likely is the pleasure to occur

- Extent or how many people will be affected by the pleasure

If the units of pleasure outweigh the units of pain, the policy or action is right, good, or just. If a choice must be made between two alternatives, the one which derives the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people should be chosen. We will introduce some critiques of this position later in the module. But for now, let’s try to apply Bentham’s utilitarianism on its own merits.

Watch ‘Law and Justice – Utilitarianism’ Jeremy Bentham:

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- According to Bentham:

- What motivates human behaviour?

- What is utility?

- How is utility linked to justice?

- Why is it important to look at aggregate happiness versus individual happiness?

- Why does Bentham believe utilitarianism can reform society?

- Identify a contemporary social circumstance where you believe ‘common sense morality’ is preventing needed social reform.

- Apply Bentham’s utility calculus to demonstrate that utilitarianism offers a better alternative

- Defend the choice as being ‘just’.

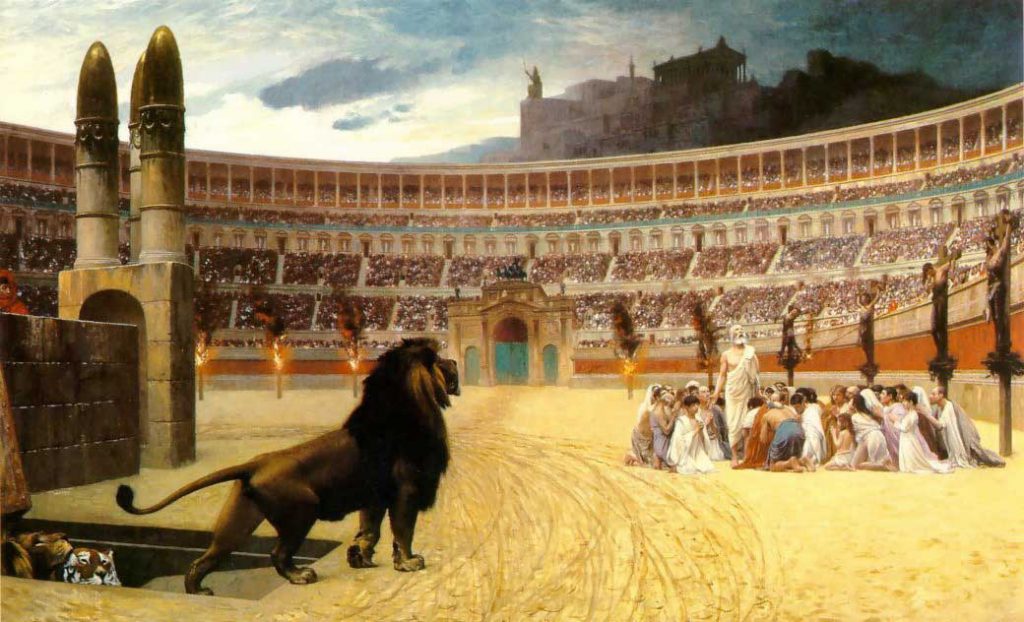

Figure 3-12: “The Christian Martyrs Last Prayer” Source Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 3-13: “Thomas Carlyle” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Elliott & Fry.

Another criticism took aim at Bentham’s reduction of all policy and action to a common currency. Bentham believed this to be a strength since it did not impose values on what policy or action was to be deemed ‘better’. Rather he argued the ‘better’ action or policy was the one that generated the greatest utility. However, that means that if more people found a base activity more pleasurable, it would be deemed better than more intellectual activities. This led Thomas Carlyle to argue utilitarianism is a ‘pig philosophy’ since it has ‘no nobler idea of well-being than the gratification of desire…’

Into this debate arrives John Stuart Mill. Mill is best known for his work On Liberty wherein he engages in a discussion on the legitimate limits of state authority over individual liberty. He does so by applying the ethic of utilitarianism to the state and society. This makes sense, given the fact he was the godson of Jeremy Bentham and that his father was a strong advocate of Bentham’s ideas. He literally grew up with utilitarianism. However, you might note a bit of a disconnect here: Mill is advocating for individual liberty and positing limits on state authority, but doesn’t such a position run counter to the democratic nature of Bentham’s utility calculus? Just think of the Christian being sacrificed to the lions for the pleasure of the Roman spectators. The Christian’s right to liberty was certainly not protected nor was the state’s authority to order his fate in any way limited. In order to make his argument Mill added a qualitative measure to Bentham’s quantitative utilitarianism by dividing pleasures into higher and lower orders. Higher pleasures are more intellectual and engage with the human desire for betterment. Lower pleasures are animalistic, based on sensation and appetites.

Mill argues lower-order pleasures alone fail to satisfy human complexity and capacity for happiness. Such lower pleasures have their place, but they alone leave people feeling ultimately dissatisfied and hollow. Human happiness requires some higher pleasures. He argues this is demonstrated by people’s unwillingness to sacrifice a higher pleasure for a greater quantity of a lower pleasure as well as their unwillingness to sacrifice a refined mental state for a lower version. He argues a ‘being of higher faculties requires more to make him happy, is capable probably of more acute suffering, and is certainly accessible to it at more points than one of an inferior type; but in spite of these liabilities, he can never really wish to sink into what he feels to be a lower grade of existence.’ This allows Mill to address the two critiques of Bentham’s utilitarianism introduced above. First, let us apply Mill’s utilitarianism to our example of the poor Christian sacrificed to the lions in the Roman Coliseum. Remember, using Bentham’s model, it could be argued that such an action is just since the pleasure derived by the spectators outweighs the pain experienced by the poor Christian. But if pleasure is divided into higher and lower orders, we could argue the pleasure of life is of a higher order and the pleasure derived by bloodlust is of a lower order. According to Mill’s logic then, the greater quantity of the lower order pleasure derived by watching someone being murdered does not outweigh the higher-order pleasure derived from life. Therefore, sacrificing Christians to the lions is unjust and the importance of individual liberty is upheld. Mill believed defending such individual liberty and the right to dissent was important for two reasons. First, protecting liberty contributes to individuals achieving those higher pleasures needed for happiness. This is because liberty encourages individuals to better develop their intellect and moral reasoning.

Mill believed people must exercise such critical faculties if they are to achieve those higher, more intellectual, pleasures and therefore their happiness.

Second, Mill believed liberty and the right to dissent were important to society. Without liberty, society may ossify, becoming inflexible, and lack the ability to challenge beliefs that may be harmful. Through liberty, dissenting opinions can speak potential truth to power, leading to self-reflection and social progress.

Taken together, the protection of individual liberty leads to utility maximization in the long run and therefore promotes the greatest human happiness. This is an important break from Bentham. Bentham’s utility was measured by immediate pleasure whereas Mill’s utility measured happiness in the aggregate or the long run.

Mill also addresses the second criticism of Bentham regarding the reduction of all policy and action to a common currency. As we have seen, he first does so by dividing pleasures into higher and lower orders, making a distinction between those that are intellectual and those that are sensory. And, as mentioned above, Mill argued higher pleasures are necessary for happiness. In some cases, the distinction is obvious – for example the right to life versus blood sport. However, in other cases that are not so obvious, how are we to qualitatively determine which pleasure is higher? Mill proposed a utilitarian test to make such a determination. He argued the qualitatively higher pleasure will be the one chosen by the majority of those who have experienced both. This falls back on his belief introduced earlier that people seek higher pleasures in order to achieve happiness; that people are more discerning than animals and therefore will rise above Carlyle’s claim that utilitarianism is a ‘pig philosophy’. There is obvious merit in Mill’s position. Most people recognize that ‘Cosmos’ is objectively better than ‘Jackass’. But there is also a weakness: it is likely that a lot more people have watched ‘Jackass’ than ‘Cosmos’. So, according to Mill, which show is the qualitatively higher pleasure? Mill would likely argue that people recognize that ‘Cosmos’ is qualitatively higher. But does that satisfy the criteria of utilitarianism if more people chose to watch ‘Jackass’ than ‘Cosmos’? Why would people choose to watch ‘Jackass’ if they know ‘Cosmos’ is better? One answer is that people are societally conditioned to believe some things are better than others. If this is true, then Mill’s qualitative aspect of utility does save utilitarianism from the claim it is a ‘pig philosophy’ but perhaps at the price of undermining the elegant simplicity and democratic basis of Bentham’s utilitarianism. In other words, it requires moral judgement to be rendered outside of the strict limits of utilitarian thought.

Watch ‘Law and Justice – Utilitarianism’ John Stuart Mill:

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- According to Mill:

- Which aspects of Bentham’s utilitarianism bothered Mill? Why?

- How does Mill seek to qualitatively ‘refine some of the coarser aspects of Bentham’s utilitarianism?

- Is he successful?

- Identify a contemporary tension between higher and lower order pleasures, specifically where the higher pleasure is recognized as such but where the lower pleasure is more often chosen

- What does this tell us about Mill and utilitarianism?

Figure 3-15: Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of jessica45.

Having examined the utilitarian positions of Bentham and Mill, let us apply utilitarianism to questions of justice. Bentham’s purer form of utilitarianism does make truth claims on justice. He argues justice is based on the principle of utility: policy or action that increases pleasure and/or decreases pain is ethically good or ‘just’. In other words, justice is achieved by creating the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number of people. This is a very democratic and impartial definition of justice. It is not based on religious scripture with clergy acting as gatekeepers in defining what is ‘just’. It is not based on norms derived by societal elites and imposed through institutions and often accompanied by structural violence. For Bentham, justice ought to be impartial, quantitatively measured, and based on equality. No one should hold a privileged position in determining what is just: neither kings nor priests nor men over women. Everyone is equal. Moreover, each decision should be judged individually in time and place. This is why Bentham argues utilitarianism provides a system of secular morality. However, as we have seen, this strict form of utilitarianism may result in policy or actions that feel unjust: think again of our poor Christian that has been sacrificed to the lions time and time again in this module.

By today’s standards, this is unjust. In a more contemporary sense, if a majority prefers a ban on the Niqab or Burqa, would it be just to enact such a policy?

Or think about the allocation of scarce resources in choosing health care provision. Should Medicare use its resources to provide care for the greatest number of people? What if that means making a large number of elderly people marginally more comfortable while sacrificing a few young people with life-threatening but rare conditions? What is the just policy choice?

Bentham sticks to his position: the policy or action that maximizes the greatest amount of pleasure and/or minimizes the greatest amount of pain for the greatest number of people is the most just. Yet many people, perhaps including yourself, may feel uncomfortable with this definition of justice. Many people would feel uncomfortable with the idea of a young child suffering in order to alleviate the less serious ailments of a greater number of elderly. So Bentham’s utilitarianism does have a sort of raw justice to it that is rendered by a pure calculation of utility.

Mill’s more humane utilitarianism also makes truth claims on justice. In fact, he took considerable pains to deal with the question of justice in much of his work and, most importantly for us, in chapter 5 of Utilitarianism. He recognized that Bentham’s principle of utility can at times be seen to be at odds with the concept of justice. This is because the principle of utility assesses happiness at the aggregate and this can lead to injustice for individuals – again think of the Roman spectators (aggregate) and our poor Christian sacrificed to the lions (individual). Mill begins his attempt to reconcile utility and justice by examining the concept of justice itself. He identifies five conceptions of justice:

- Respecting legal rights (one’s personal liberty or property)

- Respecting moral rights (pay equity between genders)

- Giving people what they deserve or just-desserts (recognition for work completed but also punishment for bad conduct)

- Keeping promises or faithfulness (following through on contracts or fulfilling obligations made between friends or family)

- Impartiality (not giving benefits to people we know, like friends or family, or based on gender or ethnicity)

But this exercise is less helpful than one would hope since these conceptions of justice at times do come into conflict. At one time slavery was legal. To deprive someone of their slaves or for a slave to run away from their owner would breach the owner’s legal rights and therefore be unjust. However, legal slavery is an unjust law and in violation of a person’s moral rights.

This brings the legal rights and moral rights concepts of justice into conflict. Mill, therefore, argues that ‘justice’ lacks a unanimous understanding of what defines it and how it should be applied. For Mill, this opens the door for a utilitarian application to justice by arguing that utilitarianism provides the only rational means to decide what is just and to resolve disputes between contested claims of justice. For Mill, justice is about protecting those things we consider valuable in society, or in other words things that have aggregate utility. We want to maximize the benefits and minimize the harm of those things that influence our happiness in the long run. We know justice deals with issues we consider to be particularly important to utility because we place sanctions or penalties on those who act unjustly. Mill argues justice is therefore constituted by two things: rules of conduct and moral sentiment. Rules of conduct lay out a decision matrix of what we should and should not do. We should respect another person’s legal right to use their private property. Conversely, we should not deprive another person’s legal right by taking their property against their will. Moral sentiment is the desire for punishment to be applied when the rules are broken. Mill notes that this desire for punishment is rooted both in our animalistic desire to retaliate for wrongs done and, when expanded to society or humanity as a whole, in our more developed intellect characterized by empathy for others. Empathy, as a higher-order function, is a demonstration of morality since it is concerned with society as a whole. Mill then links this concern for society as a whole to the issue of general utility. Specifically, he argues justice requires utilitarianism. He makes this argument through a discussion of rights and the importance of impartiality and equality.

Rights are those things that an individual can make a valid claim on society to protect. The protection of these rights provides security within society and increases the general utility. When rights are breached, security is reduced, and the general utility is decreased. If people cannot count on rights to be protected there is no basis upon which to seek further self/societal progress. Without the security of rights, the social fabric would begin to fray. Mill argues that security is the one thing that no human being can do without. This explicitly builds on Bentham’s measures of utility. Think back to Bentham’s seven quantitative measurements of happiness: Duration, Fecundity, Purity, Propinquity, Intensity, Certainty, and Extent. And apply this to the ‘pleasure of security’: without security other forms of pleasure are undermined – how likely is the pleasure of security to happen? For how long will it last? How likely will its provision provide further pleasures? The absence of security impacts not only the specific person harmed but everyone more generally: if your security is not protected today, it is possible my security may be sacrificed tomorrow. Thus, the violation of rights leads to a decline or an absence of security and will drastically reduce the general utility.

Figure 3-17: Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of GDJ.

The second concept Mills refers to in connection between justice and utility is equality and impartiality. He argues these are also important to justice. Things like corruption, nepotism, racism, and sexism, all treat people partially and on the basis of inequality. Such behaviour is unjust and undermines the first principals of utilitarianism: the greatest happiness principle. Such discriminatory action will privilege the few against the interests of the many. Mill argues the best way to achieve equality and impartiality is utilitarianism. At the heart of utilitarianism is the greatest happiness principle: to seek the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number of people. In undertaking such utility calculus, each person’s happiness is treated similarly and is by definition equal and impartial.

Therefore, both rights and equality/impartiality are necessary conditions for justice. And the attainment of each is best achieved via utilitarianism. However, in the end, the question remains – does either Bentham’s or Mill’s utilitarianism promote justice in theory? How about in Canada today?

Watch the CBC’s The National ‘Free speech under attack’:

Read Clifford Orwin’s Globe and Mail Article: “What would John Stuart Mill think about today’s campus free-speech debates?”: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/what-would-john-stuart-mill-think-about-todays-campus-free-speechdebates/article38005374/

*Warning – this video, article, and the following topic is of a controversial nature

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What is the debate surrounding free-speech on campus?

- What are the two sides of the argument?

- What is the difference/significance between:

- The University denying a controversial speaker/group on campus

- Allowing controversial speakers but also allowing protesters

- Apply the utilitarian position on justice to the free-speech on-campus debate?

- Is the general utility increased or decreased by limiting free-speech on campus?

- What is your opinion on this debate? Support your answer.

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of utilitarianism, notably that of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, and apply it to the idea of justice. Bentham consciously sought to provide a rationalist system of secular morality and in is doing brought the idea of utilitarianism to the modern era. He argued that the only rational, scientific means to adjudicate whether policy and action is good, right, and just would be to look to the basic motivators of human action: pleasure and pain. He argued that all policy and action could be reduced to a common currency in order to undertake a cost/benefit analysis. Critics of Bentham posit two big issues. First, that individual rights could be grievously harmed if the majority derives pleasure from such harm. Second, that the reduction of all policy and action to a common currency in order to facilitate cost/benefit analysis, facilitates a ‘pig philosophy’. Mill sought to address these criticisms. First, he introduced a qualitative distinction to Bentham’s quantitative assessment of pleasure. He argued that there are higher and lower-order pleasures. Lower-order pleasures are rooted in our animalistic, sensory desires. Higher-order pleasures are rooted in our intellect and a human desire for betterment. Mill believed this developed Bentham’s utilitarian concept. First, it addressed the charge of it being a pig philosophy. Second, it allowed individuals to be better by forcing them to exercise their intellect and thereby achieving fuller happiness. Third, it furthered societal progress by allowing people to dissent and challenge societal norms. If we apply both variants of utilitarianism to the issue of justice, we see two distinct contributions with weaknesses. From Bentham, we get a rough but democratic form of justice. It does provide a means to decide what is ‘just’ but it may also lead to outcomes that violate individual rights and appeal to baser forms of pleasure. From Mill, we get a more humane utilitarianism that protects rights and seeks to define happiness at the aggregate or societal level instead of the individual level. But is Mill’s utilitarianism true to Bentham’s vision? Can he defend his arguments with a strict adherence to the logic of utility? Further, as we see in the debate on the case of free-speech on campus, can utilitarianism be the basis of adjudicating what is ‘just’?

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Certainty: the likelihood a pleasure will occur in Bentham’s utility calculus

Consequentialist: a policy or action is adjudicated based on outcomes

Cost/benefit analysis: a systematic approach to estimating the strengths and weaknesses of alternatives

Duration: how long a pleasure will last in Bentham’s utility calculus

Empiricism: the practice of relying on observation and experiment

Enlightenment period: a philosophical, intellectual and cultural movement of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries which stressed reason, logic, criticism, and freedom of thought over dogma, blind faith, and superstition

Extent: the quantitative measure of how many people will be affected by the pleasure in Bentham’s utility calculus

Faithfulness: one of Mill’s five conceptions of justice defined by following through on contracts or fulfilling obligations made between friends or family

Fecundity: how likely a pleasure is to provide further pleasure in Bentham’s utility calculus

Higher pleasures: one of two orders of pleasures defined by Mill which are more intellectual and engage with the human desire for betterment

Impartiality: one of Mill’s five conceptions of justice defined as not demonstrating preferences like giving benefits to people we know, like friends or family, or based on gender or ethnicity

Individual liberty: the scope of freedom for individuals free from external restraint in the exercise of those rights which are considered to be outside the province of a government to control

Industrial revolution: took place from the 18th to 19th centuries and was a period during which predominantly agrarian, rural societies in Europe and America became industrial and urban. It fundamentally reorganized how we live, work, and organize our social relations.

Intensity: how strong the pleasure will be in Bentham’s utility calculus

Just-desserts: one of Mill’s five conceptions of justice based on an individual keeping promises, such as following through on contracts or fulfilling obligations between family and friends

Legal rights: one of Mill’s five conceptions of justice based on legally guaranteed powers available to a legal entity in realization or defense of its just and lawful claims or interests

Lower pleasures: one of two orders of pleasures defined by Mill which are animalistic, based on sensation and appetites.

Moral rights: one of Mill’s five conceptions of justice that exist prior to and independently from legal rights, based upon the identification of certain fundamental and objectively verifiable human goods

Pig philosophy: a critique of Bentham’s utilitarianism because it is rooted in sensory pleasures

Propinquity: how soon the pleasure will occur in Bentham’s utility calculus

Purity: how likely will the pleasure not be followed by pain in Bentham’s utility calculus

Qualitative: refers to the subjective quality of a thing or phenomenon

Quantitative: refers to objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data

Rationality: the recognition and acceptance of reason as the proper source of knowledge and guide to action

Relativist: the position that there is no universal rules or commandments to determine what is right and wrong. Rather context and outcomes are instrumental in such determinations

Teleological: means something has telos or purpose

Utilitarianism: a theory of ethics that posits the right policy or action is that which maximizes some measurement of utility, most often human well being or happiness.

Utility calculus: also known as felicific calculus, it uses Bentham’s seven measurements of happiness to create a common measure of comparison to determine the right, good, or ‘just’ policy or action.

References

Audi, Robert, and Gale Group. The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. 2nd ed. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Blackburn, Simon. The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. 2nd Ed., Rev.. ed. Oxford Paperback Reference. 2008.

Engelmann, Stephen, and Jennifer Pitts. "BENTHAM'S "PLACE AND TIME"." Tocqueville Review 32, no. 1 (2011): 43-66.

Hashmi, Sohail H. Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction : Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Johnson, Oliver A. Ethics : Selections from Classical and Contemporary Writers. 5th ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1984.

Macdonald, Neil. Sept 28 2005. “The niqab debate, let's not forget, is about individual rights”, CBC. Accessed March 28th, 2018. www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-election-2015-niqab-neil-macdonald-1.3246179

Orwin, Clifford. Feb 16, 2018. “What would John Stuart Mill think about today's campus free-speech debates?” The Globe and Mail. Accessed April 21st, 2018.

Skorupski, John. The Routledge Companion to Ethics. Routledge Philosophy Companions. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York: Routledge, 2010.

Upton, Hugh. "Moral Theory and Theorizing in Health Care Ethics." Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 14, no. 4 (2011): 431-43.

Welch, Patrick J. "Thomas Carlyle on Utilitarianism." History of Political Economy 38, no. 2 (2006): 377-389.

West, Henry R. "Some Implications of Utilitarianism for Practical Ethics: The Case Against the Military Response to Terrorism." In The Blackwell Guide to Mill's Utilitarianism, 249-69. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

Supplementary Resources

- Blackburn, Simon. The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. 2nd Ed., Rev.. ed. Oxford Paperback Reference. 2008.

- Johnson, Oliver A. Ethics : Selections from Classical and Contemporary Writers. 5th ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1984.

- Skorupski, John. The Routledge Companion to Ethics. Routledge Philosophy Companions. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York: Routledge, 2010.

- “Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 02: ‘Putting a price tag on life’” YouTube video, 55:09, a lecture by Michael Sandel published on Sept 8 2009, posted by Harvard University, Accessed May 1 2018, https://youtu.be/0O2Rq4HJBxw