Overview

In our last module, we looked at Kantian ethics. We saw that Kant was primarily driven by the question of how to define the moral worth of an action. He engaged with the ideas of freedom, duty, and morality, and posited a very stringent path of morality that saw the world in black and white. From this, he developed the idea of the categorical imperative which argued a righteous action must be universalizable and must treat humanity with dignity by treating people as ends and not as means. We concluded the last module with the least defined formulation of the categorical imperative which moved the discussion from the righteous act to the righteous political community. Here, Kant argued that a righteous community is possible through a Kingdom of Ends. This Kingdom of Ends is constituted by a single community governed by laws that are arrived at by the use of human reason. He argued that being based on the human capacity to reason, such a community was compatible with the categorical imperative since everyone could autonomously will it into being. In so doing, Kant is employing the idea of an imaginary social contract. It is this idea of a social contract, and specifically its formulation by John Rawls, that we turn to in this module.

Figure 7-1: "John Rawls" Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Rawls#/media/File:John_Rawls.jpg Permission: Fair Use. Courtesy of Harvard Gazette.

Rawls, perhaps more than anyone else, has developed the ideas of Kant in regard to the imaginary social contract. Many others have suggested that a social contract is necessary for legitimate governance, but most argued this was an actual contract between people who either gave their consent to the state or threatened to withdraw their consent to the state. For Kant, and later Rawls, an actual social contract between the citizens and the state was less practical and less desirable. How could such an agreement legitimately represent the will of the people many times removed from those who consented to it in the past? And even if an argument could be made that future denizens of a particular political community were bound to a social contract made by their ancestors, by what basis is it argued that the original agreement was moral or just? For example, both the French and American Revolutions, which produced two of the great social contracts of the 18th century, were highly problematic. The American Constitution gave legitimacy to slavery. The French Constitution relegated women to being passive citizens. Even when the French state recognized the rights of universal suffrage, education, and employment in 1848, it was defended by highlighting women’s role in educating their children. In Canada, women were not considered a ‘legal person’ until 1929 and status Indians were unable to vote until 1960. Are these examples of laws that were derived from human reason? In this module, we are going to look at the idea of a social contract and then specifically Rawls’ version of an imaginary social contract constructed in the ‘Original Position,’ and behind the ‘Veil of Ignorance’. For Rawls, like Kant, the imaginary social contract is a valuable exercise in addressing issues of justice. Rawls will ask us to consider by what basis we can claim the right to benefit from societal constructs and even personal attributes. He will ask to consider what a just social contract may look like devoid of self-interested bargaining. In the end, he will make a powerful argument, albeit a demanding one, of what is a just social contract. We will conclude with a discussion of the implications of the social contract, and specifically Rawls’ version of it, to justice.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Discuss the different ideas of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau regarding the social contract.

- Describe Rawls imaginary social contract and its operationalization through the Original Position and Veil of Ignorance.

- Apply Rawls’ two principles of justice to contemporary political issues.

- Read Chapter 4 in Michael Sandel’s Justice

- Watch “Do we need government?” by 8-Bit Philosophy https://youtu.be/ttu8va9_x1g

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Watch “Political Theory – Thomas Hobbes” https://youtu.be/9i4jb5XBX5s

- Watch “Political Theory – John Locke” https://youtu.be/bZiWZJgJT7I

- Watch “Political Theory – Jean-Jacques Rousseau” https://youtu.be/81KfDXTTtXE

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Watch ‘Political Theory – John Rawls’ https://youtu.be/5-JQ17X6VNg

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Charismatic authority

- Class

- Common good

- Difference principle

- Divine right to rule

- Division of labour

- English Civil War

- Equal liberty principle

- General will of the people

- Human nature

- Imaginary social contract

- Legal authority

- Max Weber

- Modern state

- Original Position

- Private property

- Privilege

- Social contract

- Territoriality

- The state of nature

- The state of war

- Traditional authority

- Veil of Ignorance

Michael Sandel, Justice, Chapter 6 “John Rawls” pg. 141-166 [Textbook]

Learning Material

What is the basis by which we govern our societies? What are the rules that we devise to do so? How are those rules agreed upon? These are essential questions to ask when seeking to define justice and its application in our political structures. This is especially true given the state and the rules by which it is constituted and applied can often be coercive. Max Weber argued the modern state is constituted through territoriality, legitimacy, and violence.

Figure 7-2: Max Weber” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Max_Weber_1894.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Territoriality means the state exercises exclusive control within mutually recognized borders. Legitimacy is conferred on particular political orders based upon charismatic authority, traditional authority, or legal authority. Charismatic authority makes some claim to knowledge or power that is unknowable to others. The argument is that only through the leader can their collective goals or well-being be attained. Traditional authority is exercised through historical structures that legitimate practices over time. These first two ideal types of state legitimacy are less common in their pure form today. More common today, or at least most often expected, is legitimation via legal authority. In other words, the state is legitimated by rules that detail the function, scope, and action of the state. For example, constitutional arrangements that specifically stipulate the reciprocal rights and obligations of states and citizens. However, we must never forget the last element of the modern state according to Weber, violence. Weber argues the state is a “human community that successfully claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory”.

Figure 7-3: The 1960s Riot Police” Source: https://flic.kr/p/eafRio Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of minoru karamatsu.

That confers upon the state an extraordinary position both in contemporary domestic and international politics: a position that has a great influence on how justice is defined, applied, and adjudicated. The idea of a social contract makes an important contribution to this discussion. When people speak of a social contract, they are referring to some form of an agreement between the state and citizens in which the citizens agree to give or withhold their consent to the state. There are different positions on social contract theory which we will discuss in the next section, but they revolve around different answers to fundamental questions and positions such as: How do we balance the need for security with the need for freedom? How should power within the state be distributed and checked? How do we define and protect basic rights? However, one of the fundamental questions that determine the kind of social contract that people believe to be necessary or desirable focuses on the state of nature, the state of war, and human nature itself. The state of nature is a hypothetical place and time before we had government or even monarchs, a place and time where people live freely without formal rules or laws. For those thinking about the form and role of government, the conditions that prevail in the state of nature are crucial to determining the type of social contract they believe to be necessary or desirable. Is this hypothetical place and time characterized by violence and a war of all against all? Or is it defined by a solitary and peaceful harmony? Your answer to this will depend on how you see human nature. Are people generally peaceful or conflictual? Cooperative or greedy? Altruistic or self-serving? The learning activity at the end of this section will try to establish your opinion on this divide. We will then first look at social contract theory more generally, followed by the specific arguments made by Rawls and the imaginary social contract. Finally, we will conclude with an application of social contract theory, and Rawls’ argument more specifically, to our discussion of justice.

Before moving on, let us determine your basic view of human nature.

Watch the video “Do we need government?” by 8-Bit Philosophy

Answer the question at the end of the video below in the the Poll:

[yop_poll id=”9″]

Figure 7-4: “Charles II” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_II_by_John_Michael_Wright.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

What is a social contract and why does it matter to our enquires into questions of justice in politics? The idea of the social contract emerged out of the contestation of the divine right to rule.

The divine right to rule argument had made things simple: the monarch had been chosen by God to rule and therefore to question the monarch was tantamount to questioning God. This is an example of a traditional basis of state authority. As the consensus around the divine right to rule began to erode, another basis of state legitimacy was needed. For proponents of the social contract theory, traditional authority should be replaced by legal authority. The basic premise is that in a state of nature, people enter into a social contract to avoid perpetual conflict or a state of war, and put the general will of the people into practice. On entering the social contract, the people constitute a body politic with a government that acts in people’s name and with their authority. From this perspective, the state is created to carry out the will of the people and to protect the people. While most proponents of the social contract would agree with what has been said so far, quite divergent views emerged from this position. The three most dominant positions were established in the work of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

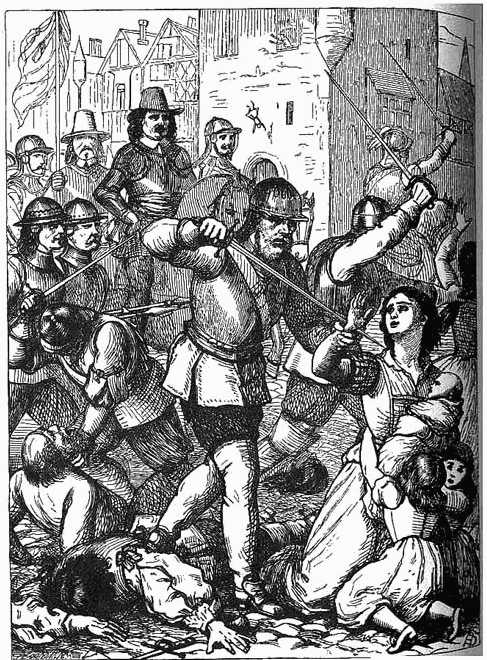

Thomas Hobbes turned his attention to the idea of the social contract during the English Civil War, 1642-1648. This was a war between the supporters of the Monarch, who preferred the traditional authority of the state, and the Parliamentarians, who wanted to transfer significant authority to Parliament. This was the bloodiest conflict in the history of the British Isles, with a conservative estimate of 180,000 deaths, or 3.6% of the population. It also included the execution of the monarch, King Charles I.

Figure 7-5: “Massacre at Drogheda” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Massacre_at_Drogheda.jpeg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Henry Edward Doyle.

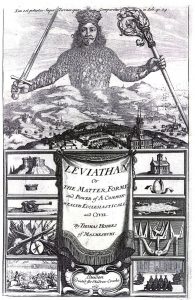

Compare this to the causalities of World War One, where about 2.6% of the population died and the scale of the conflict is evident. As in all such conflicts, the civilian population paid a high price as both sides sought to recruit soldiers, sometimes by force, and raided communities for resources. Some communities established their own militias to fend off both sides of the conflict. There emerged a widespread fear that the conflict would lead to societal norms and values disappearing, leading to a state of lawlessness and brutishness. It was in this context that Hobbes wrote The Leviathan in 1651, arguing for the centralized power of the sovereign to be based on a social contract.

Figure 7-6: “Leviathan” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leviathan_by_Thomas_Hobbes.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Hobbes sits between the two sides of the English Civil War. He rejected the Monarch’s claim to divine rule but he also rejected the argument that power should be transferred to the Parliament. Instead, he argued that political authority is based on a social contract amongst the people who are all equal: no one has any greater claim to rule than any other and most certainly no one has a divine right to rule. However, he also believed centralized authority is necessary in practice. Hobbes argued that in the absence of a centralized authority, the state of nature would prevail. The Hobbesian state of nature is constituted by self-interested citizens who compete for finite resources without a powerful actor to force civil cooperation. He famously states that life in the state of nature is characterized by “continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” It is a state of war with “every man against every man.” In such a condition there is a lack of permanence and therefore a lack of motivation to invest, to build, and to seek progress. However, he also believed people to be rational and through their own self-interest, they have the capacity to overcome the state of nature by creating a civil society. This civil society is constituted via a social contract whereby people renounce their right to impose themselves upon each other, and also empower a centralized and absolute authority, or sovereign, to enforce the conditions of the social contract. However, for Hobbes, once the social contract is constituted, people are committed to the sovereign regardless of the quality of rule since the alternative is the brutal state of nature. And to reiterate, this state of nature is the worst possible outcome according to Hobbes. Therefore, the Hobbesian social contract occupies a strange place between radically suggesting that the people are the source of both political legitimacy and of state power while also defending a more traditional position of submitting to the will of the sovereign.

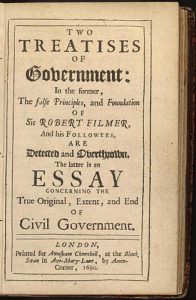

John Locke was writing at the end of the 17th century and his work on the social contract, Two Treatises of Government, was published in 1689.

Figure 7-7: “Locke Treaties” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Locke_treatises_of_government_page.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Like Hobbes, he refuted the idea of the divine right to rule and used the construct of the social contract to provide a legal basis of state legitimacy. However, his understanding of the state of nature, the rationale for the social contract, and the obligations owed to the state once created are very different than Hobbes. To start with, Locke’s conception of the state of nature stands in stark contrast to that of Hobbes. Where Hobbes imagined the bloody English Civil War as typifying the state of nature, Locke imagined it as a state of freedom, an almost idyllic state, absent any human-made restrictions on individual choice. In the state of nature, there is no state apparatus to constrain our actions and it is therefore pre-political. But it is not without morality. Locke believed the state of nature to be governed by the law of nature, which is given to us by God and is the source of all morality. Locke believed the law of nature, and therefore God, commands us all to respect each other’s life, liberty, and personal property. We are therefore prohibited from harming one another, leading to peaceful coexistence. This leaves people free to pursue their interests as they see fit. However, in this state of nature, people also must rely upon themselves to defend what is theirs since there is no civil authority to appeal to if one has been harmed or robbed. Locke recognized that once one party has used force against another, the state of nature may transform into a state of war. In a state of war, everyone is at risk of losing their property, their freedom, and even their lives. Facing such risk, Locke argues people will agree to give up their private right to self-defence and submit to the public authority of a government by consenting to a social contract. In so doing, they gain the ability to peacefully resolve conflict between individuals through laws, courts, and the executive authority to enforce legal/judicial processes. However, at this point, we see another key distinction between Hobbes and Locke. Hobbes feared the state of nature over all else and therefore argued that once the social contract has been made, individuals did not have the right to reject the sovereign. Locke on the other hand did not fear the state of nature. He argued that if the executive power of the state became tyrannical, the state would have broken the contract and put itself in a state of war with the people. The people are therefore justified, even obligated, to withdraw their consent to the social contract and openly resist executive authority. The ultimate goal would be to reconstitute a better government from the ashes of the old. Thus, unlike the Hobbesian social contract, the continued legitimacy of state authority is dependent on protecting the interests of the people, most notably, private property and personal well-being.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau also made a substantial contribution to theorizing the social contract. He critiqued the naturalized account of the social contract in the essay Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality Among Men in 1754 and published his own more normative stance in The Social Contract, or Principles of Political Right in 1762.

Figure 7-8: “The Social Contract, or Principles of Political Right” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rousseau_pirated_edition.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Like Locke and Hobbes before him, Rousseau would also argue for a legal basis of state legitimacy. However, he believed that the social contract could be problematic when it reified existing inequality. Yet he also argued the social contract as a means to overcome social inequality if it is based on direct democracy. Much like Hobbes and Locke, to understand Rousseau’s social construct we need to look at his understanding of the state of nature. For Rousseau, the state of nature was uncomplicated. People lived simple lives, relatively isolated from one another, with their needs easily met by the abundance of nature. Both the isolation and richness of resources mitigated against competition. The state of nature, therefore, lacked animosity or conflict. Rather, people’s innate morality would tend towards compassion and pity when confronting the plight of others. However, as the population grew, and communities and cities formed, the state of nature became corrupted. As the production of goods became more complicated and technology advanced, a division of labour formed, leading to class distinctions. As technology and urban living created leisure time, people began to take note of the differences in the material conditions between them and their neighbours. People noted with pride or shame their circumstances compared to others, leading to animosity and conflict. Rousseau specifically notes the role of private property in cementing the conditions of inequality. Property owners understand their privileged and precarious position. They have what others want and they are outnumbered by the masses. They, therefore, recognize the benefit of a social contract to form a civil government. However, despite the claim that such a social contract is to the benefit of everyone, it in practice exists to protect private property; to protect their privilege. As Rousseau argues “Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains”. But according to Rousseau people need not be in chains. He believed it possible to overcome the servitude brought on by the supposed progress of civilization. Freedom is possible if the social contract was founded on the general will of the people and dedicated to the common good versus the particular interests of the privileged. He argued the general will of the people can only be realized through civic participation, by bringing together all citizens to collectively decide the rules of society through direct democracy. In so doing, people are able to reconnect with their true nature, avoid the corruption brought by inequality, and be free of the chains that had enslaved us.

Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau may disagree on why people enter into a social contract. They may disagree on the obligations that result from entering into such a contract. But they all agree that a social contract provides a legal basis of state authority. However, is such a social contract just? Is the Canadian Constitution or American Constitution just? Remember that slavery was allowed under the American Constitution and women were not considered legal persons under the British North America Act of 1867. Further, to what degree are future generations bound to the original social contract? Kant sought to answer these questions by suggesting the value of an imaginary social contract. This is a thought experiment that allows us to think about what a just social contract might look like. However, Kant’s thought experiment is a bit underdefined. To more fully explore this idea, we need to wait for John Rawls, the topic of the next section.

Watch “Political Theory – Thomas Hobbes”

Watch “Political Theory – John Locke”

Watch “Political Theory – Jean-Jacques Rousseau”

*These videos cover the entire works of each philosopher. I recommend watching them in their entirety but, for the purposes of this assignment, you may choose to limit your viewing to their ideas on the social contract.

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- How do Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau view:

- The state of nature?

- The social contract?

- What do they agree/disagree on?

- Which position do you find most convincing? Why?

- Do you believe the social contract facilitates a ‘just’ political community?

- Why or why not?

- What is the basis of the social contract in Canada?

- Is it just?

- If it is, or if it were to become, unjust, what should the citizenry do?

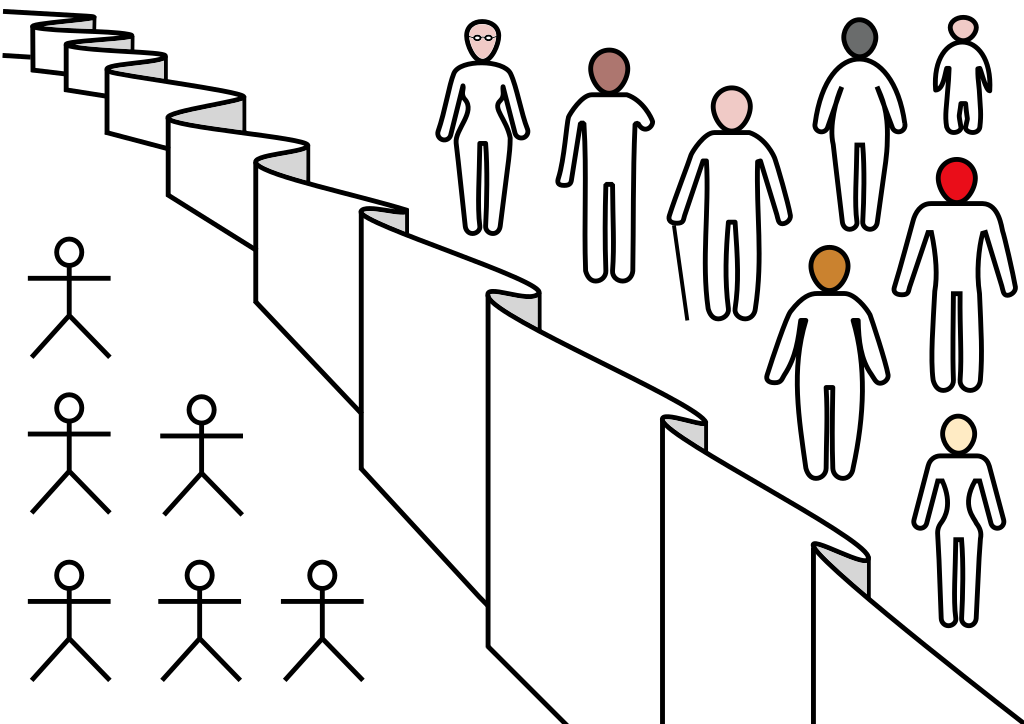

Figure 7-9: “Original Position” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Original_Position.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Philosophyink.

So under the conditions of the ‘Original Position’, what are the universal moral principles that Rawls identified? He argues that utilitarian prescriptions make little sense since there is a high possibility you may find yourself part of a disadvantaged minority group. Remember the plight of our Christian sacrificed to the lions in module three? Libertarian prescriptions are also problematic since we do not know if you will be rich or poor, healthy or unhealthy, strong or weak. You may have ‘self-ownership’ under libertarian principles but that also means you may also own your poverty, sickness, and/or characteristics that disadvantage you in society. Complete equality sounds like it may offer a solution since we would not find ourselves anymore or less disadvantaged than anyone else once the ‘veil of ignorance’ has been lifted. However, we may find ourselves equally disadvantaged compared to alternate arrangements as it is possible that even the most disadvantaged person in a minimally unequal society may be better off than everybody else in a perfectly equal society.

Rawls argues that in the ‘Original Position’ and under the ‘Veil of Ignorance’, it is possible for all rational people to discover the same two principles of justice. The first is the ‘equal liberty principle’ which stipulates each person should have an equal right to the largest degree of liberty possible. The only limitation to this right is that it may not infringe on the liberty rights of others.

Figure 7-10: “Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls” Source: https://flic.kr/p/GUodUa Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Ron Cogswell.

Rawls argues these rights include freedom of thought, liberty of conscience, political liberties, freedom of association, freedoms specified by the liberty and integrity of the person, and rights/liberties covered by the rule of law. It is important to note that Rawls argues this first equal liberty principle is superior to the second principle which governs the distribution of wealth and privilege in society. This means that liberties can not be sacrificed for greater efficiency or wealth. The second is the ‘difference principle’ which stipulates that inequality is permissible only when two conditions are satisfied. First, no one should be discriminated against in access to privilege. Second, inequality is only permissible when it provides the greatest benefit to the least advantaged members of society. This means that it is permissible for some people to have more power, income, or status if the conditions of the least well off are improved. Therefore, Michael Jordan may be permitted their status and wealth if this improves the lives of the most disadvantaged.

This could be accomplished through progressive taxation, increasing both the scale and the poor’s share of the economy, or providing greater access to a greater number of goods at a cheaper price. The same argument can be made for specialized services like doctors, dentists, or teachers. These two principles of justice form the basis of Rawls’ imaginary social contract. This stands in stark contrast to the social contract described by Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. These political philosophers were all theorizing a social contract in theory or actuality that was based on the consent of the governed to provide a legal basis of state authority. Rawls, on the other hand, is positing what rationally must be accepted if we truly want to live in a just society.

Watch ‘Political Theory – John Rawls’

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal:

- What motivated Rawls to study the concept of justice?

- Why did Rawls believe societies do not become fairer?

- How does the veil of ignorance overcome this?

- According to Rawls, what test can we use to determine whether we have achieved a fair society?

- What is the value of Rawls’ thought experiment?

- What are the weaknesses of Rawls’ thought experiment?

The concept of a social contract has played a significant role in determining what a just society might look like. There have been two distinct connections made between justice and social contracts in this module. The first was made by Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. They argued a social contract provided a legal means to legitimate state authority. They believed such a basis of state authority was clearly more ‘just’ than the traditional authority of the divine right to rule. That being said, there are certainly differences between their positions. Hobbes may have sought to debunk the divine right of the monarchs to rule, but his insistence on subsequent absolute loyalty to the sovereign, regardless of quality of rule, is questionable on the grounds of justice. Locke also questioned the divine right to rule. However, he also posited the state only maintained its legitimacy as long as it protected the interests of its citizens, most notably their private property and well-being. If the state failed to do so, the citizens had the right to withdraw consent and establish a new government. Locke’s argument on the basis of state legitimacy is more ‘just’ than the Hobbesian subservience to the sovereign. Rousseau, in turn, questioned the naturalized social contract and its focus on protecting private property. When the social contract works to protect the privilege of the few, justice for all is in question. He argued that a ‘just’ social contract requires active civic participation, particularly direct democracy. Only through such civic engagement can the social contract reflect the general will of the people and allow citizens to reclaim their freedom. This is certainly a strong justice claim.

However, all contracts, including social contracts, can be questioned on the grounds of justice. Yes, contracts have moral value in that they represent, in their purest form, express consent and reciprocity. Consent is important as it values the autonomy of the individual. Reciprocity is important as it defines the mutual benefit that each party receives from the contract. But for contracts to be just, certain assumptions need to hold true. In terms of autonomy, there is an assumption that the parties involved are relatively equal in power. In terms of reciprocity, there is an assumption that the parties are relatively equal in knowledge.

Figure 7-11: “Agree” Source: https://pixabay.com/en/agree-english-consent-contract-1728448/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Catkin.

https://pixabay.com/en/agree-english-consent-contract-1728448/] In practice, these assumptions do not always hold true; there are often imbalances in power and/or knowledge. Therefore contracts, in and of themselves, are insufficient moral instruments. Social contracts are even more problematic since they are multigenerational. This is problematic for two reasons. First, conceptions of justice change over time. In 1867, the British North American Act did not recognize women as legal persons. The American Constitution deemed slavery legal. Neither example would be considered ‘just’ by contemporary standards. Second, social contracts are binding on subsequent generations, and therefore it is questionable whether or not consent has been given and maintained. If consent is in doubt, so is the degree to which the social contract is just.

For Kant, and even more so Rawls, actual social contracts are flawed devices to seek answers of morality and justice. However, they believed the problem of contingency inherent in such contracts can be overcome by constructing an imaginary social contract where the ideals of equality in power and knowledge can be realized. For example, when Rawls asks people to imagine that they are in the ‘Original Position’ and under the ‘Veil of Ignorance’, they are stripped of their history, identity, and interests. They become rational beings asked to think about the principles of societal justice. As we saw, it is argued that as rational beings they will come to the same conclusions as to what principles would underpin a just society. And to reiterate, the Rawlsian social contract is not theorizing about what kind of social contract people have or hypothetically would agree to. It is positing what a rational person must agree to if they truly want to live in a just society. The moral side of Rawls’ argument is premised on the idea that the distribution of wealth and opportunity should not be decided arbitrarily. Rawls argues that most conceptions of distributive justice are highly arbitrary. In order to exemplify this argument, we will use the analogy of a marathon for each example.

Under the feudal system, if you were born into the aristocracy or royalty, your privilege was a product of chance and was completely arbitrary. In our marathon analogy, only those born into aristocratic households were allowed to run in the marathon, regardless of ability. Libertarian principles privilege formal equality, but people’s initial conditions are often arbitrary. Initial conditions are determined by the place and family you are born into; the personal traits, both physical and mental, you are born with; even whether you are the youngest or oldest child. In other words, everyone has the right to enter the marathon, but their starting positions are often highly unequal. Meritocratic principles seek greater equality of opportunity through social programs that seek to counter contingency. In other words, these programs seek to bring everybody to the same starting position in the marathon. However, those with natural attributes like longer legs or larger lung capacity will still win the race despite people’s individual efforts. Their victory is still, to a degree, arbitrary. Their long legs or large lungs were an accident of birth. Rawls argues for an egalitarian form of distributive justice that is devoid of arbitrariness. He posits each person should be encouraged to develop their natural talents, but also to realize that the benefits accrued do not belong to them alone. Since natural endowments are arbitrary, we should see “the distribution of natural talents as a common asset.” The benefits should be shared amongst the entire population. Further, according to the difference principle, these natural talents should be developed in order to improve the situation of the least advantaged in society. In order for the social contract to be just, it needs to be fair. Rawls recognizes that everyone has value. The fact that we reward athletes or movie stars disproportionately is not a question of what they are intrinsically worth but rather a question of what our society values. Within the constructs of society, people have the right to the rewards given. But to seek justice is to think about how society is constructed in the first place: the way things are, does not necessarily determine the way things should be. But Rawls is also making a very strong claim on justice. In essence, he is refuting our right to our own natural attributes. He is arguing that for justice to prevail, the benefits that accrue due to our strength, our height, or our intelligence are partially owned by society. He argues that in a just society, we agree “to share one another’s fate”. That we commit ourselves to the common benefit. That we run the marathon for the thrill of the race and that any prize bestowed on the winner can only be justified if it benefits the least advantaged in society. This is a strong disavowal of the libertarian principle of self-ownership – a robust position to take.

Choose one of the following two quotes by Rawls and use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- “A just society is a society that if you knew everything about it, you’d be willing to enter it in a random place.”

- According to this quote, is Canada a just society?

- Defend your answer with examples

- “We do not deserve our place in the distribution of native endowments, any more than we deserve our initial starting place in society. That we deserve the superior character that enables us to make the effort to cultivate our abilities is also problematic; for such character depends in good part upon fortunate family and social circumstances in early life for which we can claim no credit.”

- How does this quote support the establishment of a cooperative society?

- How is such a cooperative society just?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of this argument?

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of a social contract and its relation to questions of justice. We looked at two applications of the social contract. The first application was developed by Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. They were struggling with the decline of a traditional basis of legitimate authority, specifically the divine right to rule. In its place, they advocated for a social contract that could provide a legal basis of legitimate state authority. As we saw, there are significant differences in their respective positions on the rationale and form of the social contract. However, both their writing on the social contract and the debates that emerged between their respective positions are important to our discussion of justice in politics. In a social contract, the people constitute a body politic with a government that acts in the people’s name and with their authority. It is an arrangement based on legal consent instead of tradition. This is an important contribution to the discussion of justice in politics. The second application was developed initially by Kant but more substantively by Rawls. Instead of looking at the conditions and reasons why people may consent to an actual social contract, they sought to use an imaginary social contract as a thought experiment. They sought to divine the principles upon which a just society could be built. For Rawls, he uses the idea of the ‘Original Position’ where people are under the ‘Veil of Ignorance’ to build his thought experiment. Under these conditions, people are stripped of history, interests, and identity. In this state, they must consider what principles to constitute society, what principles a rational person must submit to in order to constitute a just society. Rawls argues people would agree to the ‘equal liberty principle’ and ‘difference principle’. His arguments make an important contribution to the discussion of justice in society. Specifically, his difference principle argues that inequality is permissible only when two conditions are satisfied. This means that to live in a just society requires living in a deeply cooperative society. But at a more substantial level, Rawls suggests that to live in a just society requires living in a fair society. And fairness cannot be arbitrary. We should neither be penalized nor claim benefits for the circumstances of our birth. Here Rawls is making a strong claim on a just society. In a just society, we must commit to the common benefit, to share one another’s fate.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Charismatic authority: makes some claim to knowledge or power that is unknowable to others, and it is only through the leader that their collective goals or well-being can be attained.

Class: is the social or economic social strata that an individual belongs to.

Common good: is a benefit enjoyed by all members of the society.

Difference principle: stipulates that inequality is permissible only when no one is discriminated against in access to privilege and when it provides the greatest benefit to the least advantaged members of society.

Divine right to rule: is the theory of government that holds that the sovereign’s right to rule is derived directly from God, and not from the people.

Division of labour: is the separation or assignment of work to individuals for a more efficient economic process.

English Civil War: stemmed from a dispute between Charles I and the Parliament. The division was whether the sovereign had complete over the parliament by virtue of his divine right to rule.

Equal liberty principle: stipulates that each person should have an equal right to the largest degree of liberty possible and that it may not infringe on the liberty rights of others.

General will of the people: is the will held by the collective for the purpose of the common good.

Human nature: refers to the fundamental characteristics of human beings.

Imaginary social contract: is Rawls thought experiment based on the ‘Original Position’ and ‘Veil of ignorance’ whereby people under these conditions can agree to the ‘equal liberty principle’ and ‘difference principle’.

Legal authority: is the assertion that the state is legitimated by rules that detail the function, scope, and action of the state.

Max Weber: was a prominent social theorist. Contributed to the definition of the modern state as the body that possesses the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a defined territory.

Modern state: is a defined sovereign territory with a population, ruled by a legitimate authority with the monopoly of violence.

Original Position: is where people have no knowledge of themselves nor their circumstances due to the ‘Veil of Ignorance’.

Private property: is the ownership of property, not by the government or state, but by individuals.

Privilege: is the granting of special benefits, advantages, or favors.

Social contract: is an agreement between the state and its people over the rights, duties and responsibilities owed to one another.

Territoriality: the geography over which the state exercises exclusive control within in mutually recognized borders.

The state of nature: is a hypothetical place and time before we had government or even kings, a place and time where people live freely without formal rules or laws.

The state of war: is the condition of being in conflict with others

Traditional authority: is exercised through historical structures which legitimate practices over time.

Veil of Ignorance: is a thought experiment whereby people are stripped of their history, interests, and identity, and do not know their ethnicity, religion, age, nor what talents they may have. This allows us to rationally arrive at universal moral principles as the basis of a just society.

References

Adair-Toteff, Christopher. 2014. “Review of Max Weber’s Theory of the Modern State.” Theory Culture & Society. https://www.theoryculturesociety.org/review-of-max- webers-theory-of-the-modern-state/

“Civil War.” The National Archives. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/civilwar/g4/key/

Décoste, Rachel. 2013. “The Most Discriminatory Laws in Canada’s History.” Huffington Post Blog. September 4. https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/rachel-decoste/most- discriminatory-canadian-laws_b_3932297.html?guccounter=1

Elahi, Manzoor. 2005. “What is Social Contract Theory?” Sophie Project. http://www.sophia-project.org/uploads/1/3/9/5/13955288/elahi_socialcontract.pdf

Friend, Celeste. “Social Contract Theory.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://www.iep.utm.edu/soc-cont/

Garrett, Jan. 2005. “Rawls’ Mature Theory of Social Justice: An Introduction for Students.” http://people.wku.edu/jan.garrett/ethics/matrawls.htm#2prin

Hickman, Kennedy. 2018. “English Civil War: An Overview.” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/english-civil-war-an-overview-2360806

“Jean-Jacques Rousseau.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/rousseau/

“John Locke.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/locke/

McCartney, Steve, Rick Parent. “Rawls’ Theory of Justice.” BC Open Textbooks. https://opentextbc.ca/ethicsinlawenforcement/chapter/2-10-rawls-theory-of-justice/

Ohlmeyer, Jane H. “English Civil Wars.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/English-Civil-Wars

Springborg, Patricia. 2007. The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes's Leviathan. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

“Thomas Hobbes: Moral and Political Philosophy.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/hobmoral/

“Weberian Theory of State – Explained!” Political Science Notes. http://www.politicalsciencenotes.com/theories-of-state/weberian-theory-of-state- explained/767

“Women’s Rights in France.” Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions. https://www.ohio.edu/chastain/rz/womrgt.htm

Supplementary Resources

- Morris, Christopher W. The Social Contract Theorists : Critical Essays on Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999.

- Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Rev. ed. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univeristy Press, 1999.

- Rawls, John, and Kelly, Erin. Justice as Fairness : A Restatement. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Youtube. 2009. “Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 07: “A Lesson in Lying” Harvard university, 55:05, a lecture by Michael Sandel published on 9 Sept 2009. Accessed June 16th https://youtu.be/KqzW0eHzDSQ

- Youtube. 2009. “Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 08: “Episode 08: "WHATS A FAIR START?” Harvard university, 55:06, a lecture by Michael Sandel published on 9 Sept 2009. Accessed June 29th https://youtu.be/VcL66zx_6No