Overview

Until now, all of our modules have either examined theoretical enquiries into questions of justice, like utilitarianism or libertarianism, or contested processes that influence aspects of justice, like the role played by markets. This module is looking at something a bit different, an institutional attempt to seek justice or at least an attempt to address past injustice: affirmative action. Affirmative action refers to official policies implemented with the objective of addressing under-representation of particular minority groups, women, or people with mental/physical disabilities in higher education, the work place, state institutions, and public office. Affirmative action policies are most often associated with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

Figure 8-1: "12 - Civil Rights Movement" Source: https://flic.kr/p/dSfAT3 Permission: CC BY-ND Courtesy of U.S. Embassy The Hague.

However, nearly 25% of the countries in the world have some form of affirmative action policy in place, all trying to address some form of under representation of identifiable groups. Examples of non-American affirmative action policies range from India, with one of the oldest affirmative action policies, to South Africa, which implemented policies to address the legacy of apartheid. Canada also has affirmative action policies in place. In fact, the permissibility of such policies is constitutionally enshrined in section 15, subsection 2 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. That does not mean that affirmative action policies are uncontroversial. There have been significant battles fought over both their efficacy and justness. Often advocates of affirmative action focus on past injustice, seeking to implement policies in the hope of addressing these wrongs. Others focus less on past injustice and those that were harmed, instead arguing that the diversity produced by affirmative action itself is a social good.

Figure 8-2: "Citizens of Canada" Source: https://flic.kr/p/5i7QV4 Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of ItzaFineDay.

We will also see that affirmative action has its detractors. They see it as at best well-intentioned but ineffective, or more critically, they see it as harmful. For the purposes of this module, we want to address the question of affirmative action and justice. In order to do so, we need to look at affirmative action policies, including what defines them and why they are adopted. This will be followed by a look at affirmative action policies in Canada. Finally, we will look at the nexus of affirmative action and justice.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe what affirmative action policies are

- Discuss the form of affirmative action policies in Canada

- Debate the degree to which affirmative action policies promote justice

- Read Chapter 7 in Michael Sandel’s Justice

- Take the Affirmative Action Quiz: http://highered.mheducation.com/sites/0072992212/student_view0/affirmative_action-999/self-quiz.html

- Post your score out of 10 on the live poll app

- Watch CNN’s video “This is how affirmative action began” https://youtu.be/DDOyTQPOCjg

- Read the NYT’s article “Trump Officials Reverse Obama’s Policy on Affirmative Action in Schools”. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/us/politics/trump-affirmative-action-race-schools.html

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Read the National Post Article “Rex Murphy on Affirmative Action: The shame of Fauxcohantas” https://nationalpost.com/opinion/rex-murphy-on-affirmative-action-the-shame-of-fauxcohontas

- Read the Huffpost “What’s Wrong With Affirmative Action? Ask the CBC” https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/anthony-morgan/affirmative-action-rex-murphy_b_1516686.html?utm_hp_ref=ca-affirmative-action

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Watch TED Talk “Color blind or color brave?” https://youtu.be/oKtALHe3Y9Q

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Abella Report

- Affirmative action

- Black Panther Party

- Booker T. Washington

- Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment Bill

- Brown v. Board of Education

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Civic purpose

- Civil Rights Act (1964)

- Civil Rights Movement

- Collective responsibility

- Disabilities

- Diversity

- Employment Equity Act

- Equality of opportunity

- Executive Order 10925

- Freedman’s Bureau

- Gender quotas

- Green v. New Kent County

- Individual responsibility

- Intergenerational trauma

- intersectionality

- Jim Crow laws

- Malcolm X

- March on Washington

- Martin Luther King Jr

- Nelson Mandela

- Nunavut Land Claims Agreement

- Other Backward Classes

- Pay gap

- Plessy v. Ferguson

- Public Service Employment Act

- Quotas

- Racial democracy

- Regents of the University of California v. Bakke

- Rosa Parks

- Royal Commission on Equality in Employment

- Scheduled Castes

- Scheduled Tribes

- Section 15, subsection 2 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Segregation

- South African Apartheid

- Structural violence

- The 14th Amendment

- The 15th Amendment

- The Selma to Montgomery march

- The Sharpeville Massacre

- The Soweto Massacre

- The system of reservation

- Under representation

- Visible minorities

- W.E.B. Du Bois

- World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index

Chapter 7 in Michael Sandel’s Justice [Textbook]

New York Times: “Trump Officials Reverse Obama’s Policy on Affirmative Action in Schools”. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/us/politics/trump-affirmative-action-race-schools.html [Online]

National Post: “Rex Murphy on Affirmative Action: The shame of Fauxcohantas” https://nationalpost.com/opinion/rex-murphy-on-affirmative-action-the-shame-of-fauxcohontas [Online]

Huffpost: “What’s Wrong With Affirmative Action? Ask the CBC” https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/anthony-morgan/affirmative-action-rex-murphy_b_1516686.html?utm_hp_ref=ca-affirmative-action [Online]

Learning Material

Figure 8-3: https://pixabay.com/en/emancipate-liberation-liberate-1779132/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Courtesy of johnhain.

Affirmative action policies are one of the most robust attempts to achieve social justice. They are a recognition of inequality in representation or opportunity in society. They are often adopted in contexts where such inequality is deeply structural and is recognized as being unjust. And recognition is an important qualifier here. Many states and institutions have consciously adopted deeply unjust policies: slavery, apartheid, ethnically-based internment, and residential schools for example. And this doesn’t even start on the history and legacy of imperialism and colonialism. These discriminatory policies are extremely harmful to the individuals who suffer the degradation and marginalization that these policies by definition entail. However, perhaps even more insidious is the impact of such policies on the group. These discriminatory policies can lead to intergenerational trauma and the internalization of derogatory narratives. Such internalization can manifest in harm of self or others, including family members. The identity group which could traditionally provide a support network for individuals in distress can become another layer of oppression. This is a deeply structural process that has no immediate ‘solution’. Rolling back such trauma will take generations. One purpose of affirmative action policies is to facilitate this ‘roll back’. Therefore, affirmative action is a recognition of structural violence and an attempt to address it.But it is also more than that. It is not just a recognition of past wrongs, it is also a recognition of the societal good generated by diversity. A more diverse society at all levels of authority and in all fields of endeavour has many benefits. It promotes creativity, adaptability, and learning while avoiding stagnation in society; people are able to learn from each other and consider innovative responses to problems. It also provides a diverse set of role models that people of all sorts can identify with. However, affirmative action also has its detractors, usually based on one of two arguments. The first argument being that while well-intentioned, affirmative action is ultimately ineffective and quite possibly harmful. The second argument being that affirmative action itself violates individual rights and therefore is morally unjust. In order to address these questions, we will begin by looking at what affirmative action is and the goals it is trying to address. We will then turn to affirmative action in Canada. Finally, we will conclude with an assessment of how just affirmative action is.

Before moving on, let us assess your knowledge of affirmative action

- Take the Quiz http://highered.mheducation.com/sites/0072992212/student_view0/affirmative_action-999/self-quiz.html

- On the live poll app provide your score out of 10

Figure 8-4: “Freedman’s bureau” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Freedman%27s_bureau.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Yet during this short period, Black Americans had made significant process. They held public office and achieved significant political gains. The 14th Amendment passed in 1868 providing Black Americans equal protection under the law. The 15th Amendment passed in 1870 removing “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” as grounds to be denied the vote. However, rising racism by White Americans led to ‘Jim Crow’ laws in the South.

Figure 8-5: “We Cater to White Trade only.” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WhiteTradeOnlyLancasterOhio.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Ben Shahn.

These laws imposed racial segregation, banned interracial marriages, and disenfranchised Black Americans through intentionally discriminatory voting requirements.

These ‘Jim Crow’ laws were legitimated by the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, which said the provision of separate but equal facilities was not in violation of the law. In the North, there was less legal discrimination but substantial societal discrimination in the work place, in which neighbourhoods Black Americans could live in, and what schools Black Americans could study at.

There were important battles against this racial discrimination being fought in the late 19th and early 20th century. Booker T. Washington fought for economic opportunity for Black Americans. W.E.B. Du Bois fought for the civil rights of African and African descendants globally.

Figure 8-6: “Booker T. Washington” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Booker_T_Washington_retouched_flattened-crop.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Harris & Ewing.

Figure 8-7: “W.E.B Du Bois” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WEB_DuBois_1918.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Cornelius Marion.

Figure 8-8: Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montgomery_bus_boycott#/media/File:Rosaparks_bus.jpg Permission: Fair Use.

In 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed, one of the most influential civil rights organizations. These early struggles set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement which began to coalesce during World War II. Black Americans served in the military and worked in the factories producing war material. When the War ended, many were confronted with the hypocrisy of fighting for freedom and democracy abroad and supporting the war at home while still facing systemic discrimination. During the 1950s and 60s, large scale civil rights protests began in earnest.

In 1955, Rosa Parks was famously arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a public bus. This lead to protests and a boycott of the Montgomery bus system which lasted 381 days, only ending when segregated seating was ruled to be unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court ruled segregated public schools were illegal in the case of Brown v. Board of Education in 1957. In the same year, President Eisenhower used federal troops to enforce school desegregation in Arkansas. In 1960, four black college students staged a sit-in by occupying lunch counter seats reserved for whites at the Woolworth’s drug store in Greensboro North Carolina. This led to similar supporting sit-ins across the country. In 1963, 200,000 people took part in the March on Washington, demanding civil rights legislation. It is here that Martin Luther King Jr gave his famous “I have a dream” speech.

However, participation in the Civil Rights Movement was dangerous. In the early 1960s, protestors in Alabama were routinely set upon by police with clubs and dogs. In 1965, 600 peaceful demonstrators were beaten by the police during the Selma to Montgomery march.

Figure 8-9: “Malcolm X” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Malcolm_X_March_26_1964_cropped_retouched.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Marion S. Trikosko.

In the same year Malcom X was assassinated, followed by Martin Luther King Jr in 1968. Their deaths empowered more militant means of fighting formal and informal discrimination in the US. The fight for civil rights was increasingly linked to the fight for independence by colonized people around the world. Groups like the Black Panther Party would dismiss the non-violent principles espoused by the leadership of the Civil Rights Movement, especially that of Martin Luther King Jr. Instead, they would quote Malcom X, “We want freedom by any means necessary. We want justice by any means necessary. We want equality by any means necessary.”

The demand of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States transformed the legal status of Black Americans and later other groups facing systemic discrimination. It forced the government to enforce civil rights laws and uphold civil-war era constitutional amendments like equal protection under the law and non-discrimination of voting rights. The gains of the Civil Rights Movement also became the basis of affirmative action policies.

Figure 8-10: “President Kennedy addresses nation on Civil Rights, 11 June 1963” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Kennedy_addresses_nation_on_Civil_Rights,_11_June_1963.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Abbie Rowe.

The term ‘affirmative action’ was first used in Executive Order 10925, issued by President Kennedy in 1961.

This established the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity and sought to facilitate non-discrimination employment policies in the executive branch of government. In the text of the order, it stated “the contractor will take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin”. However, it was the administration of President Johnson that actively promoted affirmative action policies to improve employment and educational opportunities for Black Americans. With the Civil Rights Act (1964), the Johnson Administration expanded the non-discrimination policies of Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925 to all private employers working with the federal government. It also made it illegal to discriminate against students in the college admissions process based on race. In 1968, Green v. New Kent County expanded the Brown v. the Board of Education decision, requiring district school boards to take the race of students, faculty, and administrators into account in the process of desegregation. In 1973, the decision in Keyes v. School District No. 1 expanded desegregation policies to Hispanic Americans. In 1978, the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke decision addressed the issue of affirmative action in higher education. It upheld the right to include race as one of the criteria by which to base admissions in pursuit of desegregation.

However, this case is also significant for another reason – the plaintiff was arguing against affirmative action. He was arguing that as a white male student, he had been the victim of discrimination because of an affirmative action policy. This is an argument that will be repeated in different forms in subsequent cases – that affirmative action policies themselves are discriminatory. The Bakke decision is also significant because it ruled that blunt instruments like racial quotas violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Therefore since 1978, the Supreme Court has sustained affirmative action policies in higher education through a number of cases, including: Hopwood v. Texas (1996), Johnson v. University of Georgia (2001), Gratz v. Bollinger (2003), Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), Fisher v. University of Texas (2013), Fisher v. University of Texas (2016).

Figure 8-11: “Rev. Al Sharpton” Source: https://flic.kr/p/dj5yYP Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Right

But the Court has also narrowed the scope to which affirmative action policies can be applied. The Court has stipulated that affirmative action admissions policies cannot be pre-eminently about race. Rather, affirmative action admissions policies are constitutional when they foster diversity amongst the student body, when they develop leadership in a diverse society, and when they foster cross racial understanding. Currently, even these supporting arguments may be coming under challenge by the Trump Administration. The administration has already rescinded seven Obama-era policy guidelines on affirmative action and, far more importantly, may have the opportunity to make long lasting changes through the Supreme Court. This is because Trump is about to nominate his second Supreme Court Justice. Trump is replacing Justice Kennedy, the traditional swing vote in the Court, and there is open conjecture that this will shift the court decidedly to the right. Since most dissenting opinions on affirmative action have come from the right, some are questioning if this signals the end of affirmative action policies in the US. There is currently a case being reviewed by the Department of Justice on Harvard’s admissions. This case is aimed for the Supreme Court, so we have our answer sooner rather than later.

For the purposes of this module, the constitutionality of affirmative action in the US is only tangentially relevant, albeit very interesting. We are asking whether such policies are just. There are two arguments that need to be assessed here. First, are affirmative action policies which are designed as compensation for past wrongs just? Second, are affirmative action policies which are designed to increase diversity just? We will be addressing these two questions in the third section of this module. Before doing so, we will look at affirmative action outside the US and specifically in Canada.

Watch CNN’s video “This is how affirmative action began”

Read the NYT’s article “Trump Officials Reverse Obama’s Policy on Affirmative Action in Schools”. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/us/politics/trump-affirmative-action-race-schools.html

Optional:

- Read Vox’s “America under Brett Kavanaugh” https://www.vox.com/2018/7/11/17555974/brett-kavanaugh-anthony-kennedy-supreme-court-transform

- Watch Last Week Tonight with John Oliver “School Segregation” https://youtu.be/o8yiYCHMAlM

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Blackboard Journal

- Why were affirmative action policies enacted?

- Why did affirmative action policies dissipate?

- What is the position of the Supreme Court on affirmative action?

- What is the position of the Trump Administration on affirmative action?

- Why may the Trump Administration’s position on affirmative action be disproportionately influential?

- Given the state of race relations in the United States today, what role do you think affirmative action could/should play?

Figure 8-12: “2011 Census Scheduled Caste caste distribution map India by state and union territory” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2011_Census_Scheduled_Caste_caste_distribution_map_India_by_state_and_union_territory.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of M Tracy Hunter.

Figure 8-13: “2011 Census Scheduled Tribes distribution map India by state and union territory” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2011_Census_Scheduled_Tribes_distribution_map_India_by_state_and_union_territory.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of By M Tracy Hunter.

In 1980, a third category called ‘Other Backward Classes’ was created comprising socially and educationally marginalized classes. Gender is also being debated as a category that should be recognized in the reservation policy, although legislation to achieve this has been stalled in the lower house since 2010. To partially ensure that the benefits of the reservation system go to those who are actually disadvantaged, there are income thresholds members of the Other Backward Classes have to meet to qualify.

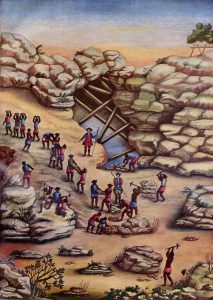

Figure 8-14: “Diamond Mining, Brazil, ca. 1770s” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Juliao06.JPG Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Carlos Julião.

In Brazil, the government began to tackle its racial issues with affirmative action policies in 2001. The two goals of Brazil’s affirmative action program are to combat racial discrimination and expand access to higher education for traditionally disadvantaged groups. This was a highly contentious decision given Brazil’s self-identification as a ‘racial democracy’ – 43% of the citizens identify as mixed-race and 30% of those who identify as white have black ancestors. However, the legacy of African slavery in Brazil has created great social disparity. The Portuguese had transported nearly 5.5 million African slaves to Brazil and it currently has the largest black population outside of Nigeria.

But Afro-Brazilians, as well as those of mixed race and the Indigenous peoples in Brazil, are largely excluded from the best schools, top positions in business and politics, and are most likely to be poor. The wealthiest 1% in Brazil are 80% white while Afro-Brazilians and those of mixed race constitute 76% of the bottom 10% of earners. In a country where there is a broad spectrum of skin colour – 136 recognized tones according to the census department – opportunity and success are most often dependant on whether one’s skin is darker or lighter. In response, the government has created a system whereby half of all university admissions are reserved for public high school graduates. Of these positions, half go to students from families making less than 1.5 times the minimum wage. Further, a percentage of spots is established in both categories by a ratio of white to non-white residents in each state, which are set aside for black, brown, and Indigenous students. One perverse complication of this system in a state with 136 officially recognized skin tones, is the necessity of creating state Ethnicity Evaluation Committees and having dermatologists with special machines to judge skin tone according to the Fitzpatrick scale. However, despite such complications, the Brazilian program is arguably one of the largest scale affirmative action systems today.

Figure 8-15: “Influence of pigmentation on skin cancer risk” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Influence_of_pigmentation_on_skin_cancer_risk.png Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of John D’Orazio, Stuart Jarrett, Alexandra Amaro-Ortiz and Timothy Scott.

Post-apartheid South Africa has entrenched the right to use affirmative action policies for redress of past discrimination in Section 9 of the Constitution. While many places, including the US and Canada, have a history of deeply institutional discrimination, South African Apartheid stands out for two reasons.

Figure 8-16: “Apartheid Sign” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ApartheidSignEnglishAfrikaans.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Dewet.

First, the move from segregation to apartheid began in 1948 with the election of the Afrikaner Nationalist Party and didn’t end until 1994. As such, it stood in stark contrast to the processes of decolonization happening around the world, even if this has at times been only rhetorically. Second, the full force of state coercion was used to enforce blatantly and unapologetic racist laws: the registration and classification of every South African according to racial population groups; strict segregation of economic and educational opportunity based on these population groups; banning inter-racial sex and marriage; restrictions on land ownership; ‘pass’ laws that controlled where and when non-white South Africans could live and work; state security laws that allowed arrest and detention without trial.

The apartheid regime increasingly had to use violence to uphold these laws, like the imprisonment of activists like Nelson Mandela (1956), the killing of 69 protestors in the Sharpeville Massacre (1960), the killing of more than 600 students in the Soweto Massacre (1976), and the questionable deaths of imprisoned activists like Steve Biko (1977).

Figure 8-17: “Non-Violence” Source: https://pixabay.com/en/non-violence-peace-transformation-1160133/ Permission; CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of johnhain.

Consecutive post-apartheid governments, all led by the African National Congress, have implemented affirmative action policies in employment and education as redress. The Employment Equity Act (EEC, 1998), the Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment Bill (B-BBEE, 2003), and the 2006 amendments to the Higher Education Act (1997) were implemented for three reasons: to provide redress for past discrimination, to increase diversity and, as a consequence, cultural understanding/reconciliation; to fulfill the potential of South Africa’s human capital. The EEC aims to achieve equity in the workplace by promoting equal opportunity in employment as well as implementing affirmative action measures to ensure equitable representation. The B-BBEE requires all businesses in South Africa to be assessed for diversity, including: ownership, management, employment equity, enterprise development, skills development, preferential procurement, and socio-economic development. Any company working with the government must have met the B-BBEE minimum requirements and all companies over a certain threshold can be penalized for not meeting these requirements. The 2006 amendments to the 1997 Higher Education Act now requires universities to increase admissions of under-represented groups. As a result, campuses like Cape Town University, which used to be 100% white, are now quite diverse. However, much like the debates in the US, there are increasing complaints that such affirmative action policies are themselves discriminatory.

Beyond race, gender is another category where affirmative action policies have sought to address under representation. In 2018, there are only 11 female Heads of State and 12 female Heads of Government. Over 150 countries still have active laws which discriminate against women, including punitive rape laws. The UN estimates that 35% of women have experienced sexual or physical violence. Significant pay gaps between men and women doing the same work exist in most countries. Around the world, women and girls are prevented from going to school, taking up jobs, and buying property to a much larger extent than men and boys.

Figure 8-18: “2013 Gender gap index world map, Gender Inequality Distribution” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2013_Gender_gap_index_world_map,_Gender_Inequality_Distribution.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of M Tracy Hunter.

In response, some countries have begun to put into place affirmative action policies. In business, some countries have introduced gender quotas in the boardroom. In 2006, Norway was the first country to introduce legislation that requires a 40% quota of women on the board of directors for listed companies. Since 2006, Belgium, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain have followed suit. Malaysia has imposed a 30% quota for women in new appointments to boards. Brazil requires a 40% quota but only for state-controlled firms. Australia and Sweden are considering such legislation, as is the UK which requires robust reporting of gender composition in companies as well as on pay equity. In politics, half of the countries in the world have some form of gender quotas in elections.

Figure 8-19: “UN Sustainable Development Goal 5” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TGG_Icon_Color_05.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of United Nations.

Quotas can be used in the process of selecting candidates for a particular riding, in the percentage of women each party fields in an election, or in reserving a specific number of seats in the legislature. These quotas can be constitutionally required or be based on a voluntary commitment by political parties. In the end, perhaps the most important metric is how many women sit in the legislature and how many of those hold positions of influence. In terms of women sitting in parliament, the top five countries in 2018 are Rwanda, Bolivia, Cuba, Iceland, and Nicaragua. In terms of women in ministerial positions, the top five countries in 2018 are Bulgaria, France, Nicaragua, Sweden, and Canada. Having better gender equality in politics is important as women provide more diversity in opinion and especially on issues of poverty where women are over-represented. The UN argues a critical mass of 30% women in the legislature is needed to change how political institutions operate.

What about affirmative action in Canada? What are the disadvantaged and/or under represented groups that need such policies? Well, the 2015 election did elect more women as Members of Parliament than ever before, but they still only constitute 26% of MPs. This not only fails to be representative of the general population, it fails to meet the 30% goal set by the UN. On the other hand, Canada’s gender balanced cabinet at least puts the Trudeau Government in a better light. But even that cannot compensate for the fact that Canada has slipped in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index from 14th position in 2006 to 35th position in 2016.

Green = least Inequality Yellow = moderate inequality Red = most inequality

Figure 8-20: “Global Gender Gap Report 2017” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Global_Gender_Gap_Report_2017.png Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of WEF.

This regression is due to issues like the fact that women only make up 26% of MPs, the stubborn pay gap, the minimal representation of women on the boards of Toronto Stock Exchange listed companies, over representation in low paying and vulnerable positions, and a lack of support services like affordable/accessible child care. The disadvantage that women face in Canada can also be intersectional with being Indigenous. As we saw in Module One, Indigenous peoples in Canada have faced intense systemic disadvantage and discrimination. They are 2.1 times more likely to be unemployed; 6.1 times more likely to be murdered; 10 times more likely to be incarcerated; 2.7 times more likely to drop out of school. Infant mortality rates are 2.3 times the national average. Young indigenous men are 10 times more likely to commit suicide than their non-indigenous counterparts and for young indigenous women it is a staggering 21 times more likely. This highlights the point above on intersectionality. Indigenous women are 3.5 times more likely to be victims of violence and their homicide rate is 7 times the rate of non-indigenous women. Indigenous women also face higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and access to social services. Again, as we saw in Module One, explanations that seek to understand such tragic statistics point to issues of racism, under funding of First Nation schools, health and public services, the condition of so many First Nation reserves, and the generational trauma that can be traced back to things like the residential school system.

Figure 8-21: “MMIW Protest” Source: https://flic.kr/p/e1Wt7N Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of blogocram.

People living with disabilities, both physical and mental, constitute another disadvantaged group in Canada. People living with disabilities in Canada face difficult obstacles simply managing day to day activities and even more employment obstacles. There is a lack of government support, a lack of accessible transportation, a lack of employment opportunity, a problem of jurisdictional clarity, and a lack of understanding in the general public of the problems faced by people with disabilities. For those who have moderate to severe disabilities as children, the obstacles magnify when they become adults. There is little to any funding for specialized health care, support for home care, and strategies to allow people with disabilities to participate meaningfully in society. However, much of the evidence for these claims is anecdotal since it is difficult to even assess the scope of the disadvantages faced by Canadians with disabilities since there is no federal mandate to collect data on disability issues. This may be changing as the Trudeau Government has introduced the Canadian Survey on Disability in 2016. The last group identified as facing discrimination in Canada are visible minorities. According to the 2016 Census, total income for visible minorities was 26% lower than non-visible minorities. These numbers get worse for recent immigrants, falling to 37% below incomes for natural born Canadians. Moreover, this is a growing problem since 22% of Canadians report being from a visible minority community, including 51.5% of Torontonians, Canada’s largest city. And don’t forget intersectionality: If you are an Indigenous woman with a serious disability or a member of a visible minority with a serious disability who has recently immigrated into Canada, you face significantly higher obstacles to success in Canada.

Let us turn back to affirmative action – what is being done in Canada to address these issues? First, unlike the US, the right to implement affirmative action policies are constitutionally entrenched in Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Section 15, subsection 1 entrenches equality rights for all Canadians. Subsection 2, however, allows for affirmative action policies which may by definition privilege one group over another if it is done to address issues of persistent disadvantage. Section 15 reads as follows:

15. (1) Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.

15. (2) Subsection (1) does not preclude any law, program or activity that has as its object the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups including those that are disadvantaged because of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is an important document in providing all citizens with constitutionally protected rights. But it is Section 15 Subsection 2 that we are interested in this module: the constitutionality of affirmative action. However, despite affirmative action being constitutional, there are far fewer affirmative action policies in Canada than the US or other countries. At the federal level, the Employment Equity Act (EEA) was passed in 1986 and amended in 1995. It is the most prominent example of an affirmative action policy at the national level. In 1983, the Trudeau Government introduced the Federal Affirmative Action Program that sought to increase the representation of women, Indigenous peoples, and persons with disabilities in the federal public sector.

Figure 8-22: “Justive Rosalie Silberman Abella” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20170125_GlobalJuristAward_Abella_(cropped).jpg Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Randy Belice.

The Royal Commission on Equality was also established at this time to study how best to meet the affirmative action goals of the government. In 1984, the Commission released the ‘Abella Report’ that made several recommendations including: changing the term ‘affirmative action’ to ‘employment equity’ because of the debates over affirmative action in the US and implementing mandatory employment equity laws.

In 1986, the federal Employment Equity Act was passed, requiring federally regulated private sector companies and crown corporations to remove barriers to employment for women, Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, and visible minorities. This means more than treating all applicants equally. It means putting into place positive policies for the recruitment of people from these four identified disadvantaged groups. On the civil society side, the National Employment Equity Network is created in 1988 to lobby the government in order to effectively implement the EEA. In 1995, the EEA is revised so that it applies to the federal public service. In 2000, a voluntary program called ‘Embracing Change’ was launched with the goal of achieving a 20% hiring goal for racialized people. The goals were not met and the initiatives funding was not renewed. In 2006, the Public Service Employment Act was adopted and sets some guiding principles for hiring practices, including ‘representativeness’ which requires a check on bias, the removal of systemic barriers, and seeking a public service that reflects the Canadian population. In 2007 and again in 2010, the Senate Standing Committee on Human Rights has released reports critical of the efforts to achieve representativeness in the federal public service.

Figure 8-23: “Prime Minister Stephen Harper” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stephen_Harper_by_Remy_Steinegger_Infobox.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of By World Economic Forum – Remy Steinegger.

The Harper Government pushed back against the EEA by cancelling the long form census and thereby hampering data collection on employment equity and more directly by removing requirements for employment equity for federal contractors.

Yet despite reports arguing that the EEA has not gone far enough in addressing disadvantage, there has been substantial public criticism of the program, and subsequently, much political manipulation of this criticism. In 2010, Sara Landriault was denied the ability to apply for a job in the federal ministry of Citizenship and Immigration because she was white. In response, the Harper Government launched its review of the EEA. Such stories have continued to be published, including a letter to the editor published in the Global Mail on April 22nd, 2018. The author recounted an exchange with a recruiter where he was told that despite being well qualified, he couldn’t be hired because he was a white male. These arguments closely reflect the debates being heard in the US.

Beyond the policies at the national level in Canada, the provinces have also enacted varying degrees of affirmative action policies as have universities. Between 1993 and 1995, Ontario experimented but eventually abandoned its own Employment Equity Act. Under Article 23 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, signed in 1993, the government is required to increase Inuit representation in government employment and develop employment training programs. In 2001, Québec implemented a number of affirmative action policies: it amended the Québec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, enacted its own employment equity legislation, and implemented an Affirmative Action Contract Compliance Program. These policies mirror the EEA quite closely but also recognizes as a disadvantaged group people “whose mother tongue is neither French nor English”. In higher education, many Canadian colleges and universities have a range of affirmative action policies. For example, Dalhousie University’s Medical School has an affirmative action policy for African Nova Scotians and Indigenous persons of the Maritime region but only if the applicants meet the admission prerequisites. Another example can be found at the University of Manitoba’s Education program which targets 45% of its admissions from five diversity categories: Indigenous, racialized, LGBTQ, persons with disabilities, and disadvantaged. These schools are able to draft affirmative action policies because of Section 15, subsection 2, of the Charter. But that does not mean they are uncontroversial. Despite the statistics regarding disadvantaged groups in Canada discussed earlier, many in Canada believe in the positive narrative of Canada as an uncontested multicultural state. Many question the need for such policies, even with ample evidence that inequality exists.

Read the National Post Article “Rex Murphy on Affirmative Action: The shame of Fauxcohantas” https://nationalpost.com/opinion/rex-murphy-on-affirmative-action-the-shame-of-fauxcohontas

Read the Huffpost “What’s Wrong With Affirmative Action? Ask the CBC” https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/anthony-morgan/affirmative-action-rex-murphy_b_1516686.html?utm_hp_ref=ca-affirmative-action

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Blackboard Journal:

- What is Rex Murphy’s argument vis-à-vis affirmative action?

- In what way does he argue affirmative action policies create a paradox?

- How does Anthony Morgan turn the tables on Rex Murphy?

- How does he equate the CBC and the CRTC to affirmative action?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of this argument?

- Do you agree the CBC and the CRTC are forms of affirmative action?

- Why or why not?

- At a broader level, what role do you think affirmative action policies should play in Canada?

Figure 8-24: “African-American university student Vivian Malone entering the University of Alabama in the U.S. to register for classes as one of the first non-white students to attend the institution. ” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vivian_Malone_registering.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Warren K. Leffler, U.S. News & World Report Magazine.

The second argument is that affirmative action policies are a means to compensate for past wrongs. Take for example a descendant of a slave or a descendant of a residential school survivor. The institution of slavery and residential schools not only imposed deep scars upon the people who suffered through them, they created long lasting discriminatory structures and intergenerational trauma. In other words, people several generations removed from the initial harm are still facing discrimination and disadvantage. Would it be just to implement affirmative action policies in order to make amends for past wrongs, or to compensate for the disadvantage that can be traced back to past wrongs? To make the question a bit tougher, is it just to disadvantage another, who had no hand in creating that harm, in order to compensate for past wrongs? To make the question even tougher, should an affluent and successful member of a disadvantaged group be given preference over another candidate that may have faced more individual disadvantage? The answers to these questions depend on a couple of positions. First, it depends on whether you subscribe to the idea of collective responsibility or individual responsibility. Collective responsibility argues that the group can bear the moral responsibility for the harm done to others. And if they are morally responsible for harm, they are also responsible for redress.

Figure 8-25: “Jews from Carpathian Ruthenia arrive at Auschwitz-Birkenau” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:May_1944_-_Jews_from_Carpathian_Ruthenia_arrive_at_Auschwitz-Birkenau.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Think for example of the Holocaust. Was Hitler alone responsible for the harm? Can the responsibility be limited to members of the Nazi Party? How about the rank and file members of the German army? What about the German citizenry? Does the international community hold at least some responsibility? What about the Canadian Government of Mackenzie King for refusing Jewish refugees entry? What about the German state or German citizenry today? Is there a hierarchy of responsibility? And if there is a hierarchy of responsibility, what are the implications regarding redress? To whom is redress owed?

On the other hand, if you subscribe to the idea of individual responsibility, it is argued that we can only be held to account for those things we have actually done. We cannot be held to account for things we did not do, even if done by our state or descendants, and certainly not for things that were done before we were even born. This is a difficult position. Harm has been done in the past and people are suffering now because of it. But is it just to ask individuals, who were not party to the original harm, pay for what is needed to address it. Second, we need to consider what is needed for redress. For some harm, important steps can start with recognition and apologies. For example, both the Harper and Trudeau governments apologies for the harm of the residential school system. Sometimes more is needed, like affirmative action policies that provide preferential treatment to people from disadvantaged groups or groups that have faced historical discrimination, for example, the quotas reserved for Afro-Brazilians in the admissions to the best institutions of higher education. And sometimes even more is needed, such as reparations for past harms. For example, payments made by the Canadian Government to survivors of the residential school system and the Japanese who were forcibly put into internment camps during World War Two. It is also important to note here that one type of redress doesn’t preclude others, as we have seen in the apologies and reparations paid to survivors of the residential schools. We will leave this discussion here as we will be covering it in more detail in Module 10.

The last justification for affirmative action policies, and the position most often used, is in the pursuit of diversity. This does not require attempting to amend for past harm as a rationale. Neither is it trying to correct for systemic bias or personal circumstances. Rather, it is arguing that achieving greater diversity is a social good in and of itself. That it is a benefit not just to those people whose interests are advanced under the policies but to everybody, to the common good. A diverse campus, a diverse workplace, a diverse government has tangible benefits. Diversity brings a wider set of viewpoints that better reflect society at large. It promotes better awareness of racial, ethnic, class, geographic, and gender based issues. On campus this has the potential to produce better teachers, lawyers, doctors, and politicians. These people have the potential to be better leaders in the classroom, the courts, in hospitals, and in legislatures. Not only may this produce better public policy and social services, it empowers those from disadvantaged groups by demonstrating that they have a meaningful role to play in society. They have role models to emulate. Advocates argue diversity therefore has a civic purpose.

Figure 8-26: “Reach Toronto – The Monument to Multiculturalism by Francesco Perilli in Toronto” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reach_Toronto.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of paul (dex)

However, in order for the diversity argument to be considered just, one objection must be overcome. Unless you are an ideologically committed utilitarian, how can it be considered just to sacrifice individual rights for a civic purpose? If university admissions or public service positions take race, gender, or disabilities into account, are they not denying access to others for those places? There is no question that it was constitutional that Sara Landriault was denied the ability to apply for a federal position in Citizenship and Immigration Canada. But was it just? Shouldn’t decision-making be based on merit alone? Well, according to Rawls, it was just to deny Ms. Landriault. It was just because she is not owed some moral dessert because of qualities she may possess. She is entitled to compete for rewards with the system once it is designed. Rawls would be more concerned as to whether the design of the system privileged the interests of most disadvantaged. In the case of the EEA, it sought to do just that – increase the representation of disadvantaged groups. Not all agree with this position, including the subject of our next module, Aristotle.

Watch TED Talk “Color blind or color brave?”

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Blackboard Journal

- Why wasn’t the election of Barak Obama as president the end of racial discrimination in the US?

- Let’s adapt Hobson’s thought experiment. Imagine you walked into the boardroom of a major Canadian company and everybody was from a disadvantaged group that was different than you. Say 100% women or 100% Indigenous. How would you feel?

- Why is colorblindness a problem?

- How is it different from being color brave?

- Why does Hobson argue diversity is a strength?

- Why does she argue diversity is critical for future generations?

- Apply Hobson’s talk to Canada. What would being ‘brave’ look like? What kind of questions do we need to have on the issue of diversity?

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of affirmative action. Unlike most of our previous modules, the focus here has not been on a theory but rather a practice. Affirmative action is an institutional attempt to seek justice or at least an attempt to address past injustice. It refers to official policies implemented with the objective of addressing under-representation of particular minority groups, women, or people with mental/physical disabilities in higher education, the work place, state institutions, and public office. Affirmative action is most closely associated with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States but such policies can be found to varying degrees in over 150 states, including: one of the world’s oldest affirmative action programs in India; one of the world’s most robust affirmative action programs in Brazil; one of the most challenging affirmative action programs in South Africa. Canada has constitutionally entrenched the right of affirmative action policies in Section 15, subsection 2 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. However, despite this, there are relatively few such policies. The most significant affirmative action policy is the Employment Equity Act (1986). Provincially, Quebec has mirrored federal efforts most closely and the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement of 1993 requires increased Inuit representation in government employment and the development of employment training programs. In assessing whether affirmative action policies can be reconciled with justice, three arguments were introduced: correcting for bias or personal circumstances, compensating for past wrongs, and promoting diversity. The first argument, correcting for bias, poses no obstacle to justice since the intent is to find the best candidates. The second argument, compensating for past injustice, does pose a challenge to the notion of justice. It is argued the crux of this tension depends on whether you adhere to the notion of collective or individual responsibility. This will be dealt with in more detail in the next module. The last argument, promoting diversity, can be reconciled with justice if you take a Rawlsian position that divorces fairness from moral desert. Instead, Rawls would be concerned with the justice of the system and whether the design of the system privileged the interests of most disadvantaged. This is the express purpose of affirmative action policies. However, as we will see in the next module, not everybody agrees that questions of justice and fairness can be divorced from questions of moral desert.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Abella Report: made several recommendations on how best to meet the affirmative action goals of the Canadian government, including changing the term ‘affirmative action’ to ‘employment equity’ because of the debates over affirmative action in the US and implementing mandatory employment equity laws.

Affirmative action: refers to official policies implemented with the objective of addressing under-representation of particular minority groups, women, or people with mental/physical disabilities in higher education, the work place, state institutions, and public office.

Black Panther Party: was a revolutionary Marxist group originally created to patrol and protect African American neighborhoods from police brutality and called for the arming of African Americans.

Booker T. Washington: was an activist and intellectual who is recognized for his educational advancements and promotion of economic self-reliance among African Americans.

Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment Bill: is a strategy intended to advance the economic transformation and advancement of Black Africans in the South African economy.

Brown v. Board of Education: The 1957 US Supreme Court ruling that held that segregated public schools were illegal.

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms: is a bill of rights entrenched in the Constitution of Canada, 1982.

Civic purpose: is a desire to contribute to one’s society through participation in the civic and political system.

Civil Rights Act (1964): is the expansion of the non-discrimination policies of Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925 to all private employers working with the federal government. Further, it made it illegal to discriminate against students in the college admissions process based on race.

Civil Rights Movement: was a political and social movement that peaked in the mid 1950’s to the late 1960’s that strived for African Americans to have equal civil rights to the whites in the US.

Collective responsibility: argues that the group can bear the moral responsibility for the harm done to others, and if they are morally responsible for harm, they may also be responsible for redress.

Disabilities: are a physical or mental impairment with one’s ability to engage in certain tasks, activities and/or interactions.

Diversity: is the presence of variety, the inclusion of different types of people.

Employment Equity Act: is designed to achieve workplace equality. It goes further than treating people equally, and includes making provisions for special measures and the accommodation of differences.

Equality of opportunity: is the principle that there should be an equal level playing ground and people ought to be able to compete on equal terms.

Executive Order 10925: established the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity and sought to enforce non-discrimination employment policies by contractors hired by the federal government.

Freedman’s Bureau: was set up to provide relief to tens of thousands of former black slaves and dislocated southern whites. It provided food and clothing, medical treatment, legal services, employment, and even settlement on confiscated land.

Gender quotas: are explicit requirements on the number or percentage of representation by a particular gender, usually women and most often in political seats or in company boardrooms. The goal is to address underrepresentation of one gender over another.

Green v. New Kent County: is the 1968 case which expanded the Brown v. the Board of Education decision, requiring district school boards to take the race of students, faculty, and administrators into account in the process of desegregation

Individual responsibility: is the argument that we can only be held to account for those things we have actually done.

Intergenerational trauma: occurs when the negative effects of a historical oppression are passed on from generation to generation.

Intersectionality: is the theory that asserts that the overlap of various identities contributes to the specific kind of oppression that the individual experiences.

Jim Crow laws: imposed racial segregation, banned interracial marriages, and disenfranchised Black Americans through intentionally discriminatory voting requirements

Malcolm X: was a human and civil rights activist who promoted the advancement of African American rights by any means necessary.

March on Washington: was a political demonstration in 1963 to protests racial discrimination and to support pending civil rights legislation in Congress.

Martin Luther King Jr: was a prominent civil rights activist who led the movement that succeeded in ending legal segregation in the US.

Nelson Mandela: was the first black president of South Africa and a civil rights leader who helped to end the country’s apartheid system of racial segregation.

Nunavut Land Claims Agreement: gave the Inuit of the central and eastern Northwest Territories a separate territory called Nunavut and is the largest Aboriginal land claim settlement in Canadian history. It also obliges the government to increase Inuit representation in government employment and develop employment training programs.

Other Backward Classes: collective term used by the Government of India to classify castes which are socially, educationally or economically disadvantaged. It is the third category recognized by the Indian Government to which affirmative action policies are applied to.

Pay gap: is the discrepancy in earnings or the difference in remuneration between men and women who are working.

Plessy v. Ferguson: was the US Supreme Court’s decision that legitimized the Jim Crow Laws. It said that the provision of separate but equal facilities was not in violation of the law.

Public Service Employment Act: sets some guiding principles for hiring practices, including ‘representativeness’ which requires a check on bias, the removal of systemic barriers, and seeking a public service that reflects the Canadian population.

Quotas: are a fixed minimum or maximum amount of people allowed to do something.

Racial democracy: is a term commonly adopted by Brazilians to describe its race relations and problematically characterize Brazilian society as tolerant and conflict-free.

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke: decision addressed the issue of affirmative action in higher education by upholding the right to include race as one of the criteria by which to base admissions in pursuit of desegregation.

Rosa Parks: was a civil rights activist that sparked the bus boycott by refusing to give up her seat in violation of the racial segregation laws. It led to the Supreme court decision that bus segregation was unconstitutional

Royal Commission on Equality in Employment: was established in 1983 to study how best to meet the affirmative action goals of the government in Canada.

Scheduled Castes: are the protected group of the Dalits or ‘untouchables’ under the system of reservation in India.

Scheduled Tribes: are primarily the isolated indigenous tribes protected under the system of reservation in India.

Section 15, subsection 2 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms: allows for laws, programs, or activities that contradict the equality provisions of section 15, subsection 1, if the purpose is the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged persons or groups. In other words, affirmative action polices are constitutionally protected.

Segregation: is the restriction of people’s access to facilities, institutions, residences and so on because of their race, or another social characteristic.

South African Apartheid: was an institutionalized system of racial segregation under a system of legislation created by the all-white government and enforced by the coercive state apparatus.

Structural violence: is the systematic oppression of disadvantaged groups by social structures.

The 14th Amendment: passed in 1868 providing Black Americans equal protection under the law.

The 15th Amendment: passed in 1870 removing “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” as grounds to be denied the vote.

The Selma to Montgomery march: was a 54-mile march for the right of African Americans to vote that was characterized by violence from the local authorities and white vigilante groups.

The Sharpeville Massacre: was the violent response by the police to a protest against apartheid in the black township of Sharpeville that killed or wounded 250 blacks.

The Soweto Massacre: was a violent response by the police in Soweto to a protest against the government requirement that the language of the white minority, Afrikaans, be used as a medium to teach in black Soweto high schools.

The system of reservation: is a policy entrenched in India’s 1950 constitution that identifies designated groups as being disadvantaged and sets quotas for them in public jobs, places in publicly funded institutions of higher education, and even elected assemblies. The three protected groups are the scheduled castes, the scheduled tribes and in later years, other backward classes.

Under representation: is the state of being disproportionately represented in relation to the larger population.

Visible minorities: in Canada are individuals who are neither Caucasian nor aboriginal.

W.E.B. Du Bois: was a sociologist and activist who fought for the civil rights of African and African descendants globally.

World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index: measures countries gender parity and tracks their progress towards it

References

“2018, women and political leadership – female heads of state and heads of government.” Women in International Politics. https://firstladies.international/2018/02/20/2018-women-and-political-leadership- female-heads-of-state-and-heads-of-government/

“50% population, 25% representation. Why the parliamentary gender gap?” CBC News. 2015. http://www.cbc.ca/news2/interactives/women-politics/

“Aboriginal Peoples and Historic Trauma.” National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. https://www.ccnsanccah.ca/430/Aboriginal_Peoples_and_Historic_Traum a.nccah

“Affirmative Action Programs in Quebec: Review and Prospects.” National Library of Canada. http://www.cdpdj.qc.ca/Publications/resume_bilan_PAE_anglais.PDF

“Affirmative Action Statement.” Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine. https://medicine.dal.ca/departments/core-units/admissions/about/affirmative- action-policy.html

“African American Records: Freedmen’s Bureau.” National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/freedmens-bureau

“Alleviating Poverty Among Canadians Living with Chronic Disabilities.” Every Canadian Counts. February 2017. http://everycanadiancounts.com/wp- content/uploads/2017/12/ECC%20Submission%20to%20HUMA%20PRS%20- %20FINAL.pdf

Anderson. Nic. 2017. “What white South Africans don’t understand about affirmative action.” The South African. October 10. https://www.thesouthafrican.com/what- white-people-dont-understand-about-affirmative-action/

“A history of Apartheid in South Africa.” South African History Online. http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/history-apartheid-south-africa

“Brazil approves affirmative action law for universities.” BBC News. 8 August 2012. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-19188610

“Canada” World Economic Forum http://reports.weforum.org/feature- demonstration/files/2016/10/CAN.pdf

“Collective Responsibility.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 8 August 2005. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/collective-responsibility/

De Oliveira, Cleuci. 2017. “Brazil’s new Problem With Blackness.” Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/04/05/brazils-new-problem-with-blackness- affirmative-action/

“Education experts spar over affirmative action at University of Manitoba.” CBC. 16 February 2016. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/university-manitoba- affirmative-action-1.3450334

“Employment equity and human rights.” Government of Canada. https://canadabusiness.ca/government/regulations/regulated-business- activities/human-resources-regulations/employment-equity-and-human-rights/

“Employment equity in federally regulated workplaces.” Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social development/programs/employment-equity.html

“Facts and figures: Leadership and political participation.” UN Women. http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political- participation/facts-and-figures

“Facts about women in politics in Canada.” Equal Voice. https://www.equalvoice.ca/facts.cfm

“Fisher V. Texas.” National Confederation of State Legislatures. June 2016. http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/affirmative-action-court-decisions.aspx

“For Affirmative Action, Brazil Sets Up Controversial Board To Determine Race.” NPR Radio Transcript. 29 September 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/09/29/495665329/for-affirmative- action-brazil-sets-up-controversial-boards-to-determine-race

Friesen, Joe. 2010. “Tories take aim at employment equity.” The Globe and Mail. July 22. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/tories-take-aim-at- employment-equity/article1389384/

Gayle, Caleb. 2018. “Supreme court pick could put 40 years of affirmative action precedent at risk.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/law/2018/jul/07/supreme-court-pick-affirmative-action-precedent

“Gender Quotas Database.” International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/gender-quotas/quotas

“Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.” UN Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/

Green, Michael. “Reparations for Slavery.” Political Philosophy. http://carneades.pomona.edu/2016f-Political/16.BoxillReparations.html

Kelto, Anders. 2011. “Inequalities Complivate S. Africa College Admissions. NPR. May 10. https://www.npr.org/2011/05/10/136173961/inequalities-complicate-s-africa-college-admissions

Knoll, Jared. 2018. “It’s time to stop dehumanizing Canadians with disabilities.” Upstream. April 3. http://www.thinkupstream.net/stop_dehumanizing

“Legislated Employment Equity Program.” Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social- development/programs/employment-equity/leep.html

Lloyd, Marion. 2015. “A decade of Affirmative Action in Brazil: Lessons for the Global Debate.” Advances in Education in Diverse Communities: Research, Policy and Praxis 11: 169-89. https://www.ses.unam.mx/integrantes/uploadfile/mlloyd/Lloyd_ADecadeOffAffirmativeActionInBrazil.pdf

Monsebraaten, Laurie. 2017. “Income gap persists for recent immigrants, visible minorities and Indigenous Canadians.” The Star. October 26. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2017/10/25/income-gap-persists-for-recent- immigrants-visible-minorities-and-indigenous-canadians.html

Moses, Michele S. 2010. “Moral and Instrumental Rationales for Affirmative Action in Five National Contexts.” Educational Researcher 39(2): 211-28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/27764584.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A62505a3fd0 41061baaa88f64c3b11240

Moses, Michele S, Laura Dudley Jenkins. 2017. Affirmative action around the world.” The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/affirmative-action-around-the-world-82190

“Next Supreme Court Justice May Help To Define Affirmative Action Cases.” NPR Radio Transcript. 5 July 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/07/05/626049360/next-supreme-court-justice-may-help-to-define-affirmative-action-cases

Olive, David. 2016. “Canada’s gender equality regression is a problem that must be solved: Olive.” The Star. December 3. https://www.thestar.com/business/2016/12/03/canadas-gender-equalityregression-is-a-problem-that-must-be-solved-olive.html

Olorunshola, Yosola. 2016. “7 appalling facts that prove we need gender equality now.” Global Citizen. May 25. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/shocking-facts-gender-inequality-international-wom/

Sawchuk, Joe. 2011. “Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. October 31. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/native-people-social- conditions/

Torjman, Sherri. 2017. “Canada’s ‘Welfare Wall’ Traps People With Disabilities.” Huffpost Blog. July 28. https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/sherri-torjman/canadas-welfare-wall-traps-people-with-disabilities_a_23049558/

Vilet Jacque. 2010. “Affirmative Action – A Global Issue.” International HR Forum. https://internationalhrforum.com/2010/10/29/affirmative-action-a-global-issue/

Wachal, Robert S. 2000. “The Capitalization of Black and Native American.” American Speech 75(4): 364-5. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/2793

“Women’s Reservation Bill: The story so far.” The Hindu. 7 March 2015. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/womens-reservation-bill-the-story-so-far/article6969294.ece

Yudof, Mark G, Rachel F. Moran. 2017. “Affirmative Action: Why Now and What’s Next?” The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Affirmative-Action-Why-Now/240843

Supplementary Resources

- Park, Julie J. When Diversity Drops. Rutgers University Press, 2013.

- Skrentny, John David. The Ironies of Affirmative Action : Politics, Culture, and Justice in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Weinfeld, Morton. "The Development of Affirmative Action in Canada." Canadian Ethnic Studies 13, no. 2 (1981): 23-39.

- 2009. “Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 09: “Arguing Affirmative Action” Harvard university, 55:00, a lecture by Michael Sandel published on 9 Sept 2009. Accessed July 13th