by Veronica Kmiech, BMUHON, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan

This work is part of a larger research project titled “Local Music Collections” led by Music Librarian Carolyn Doi and funded by the University of Saskatchewan President’s SSHRC research fund. A post from Carolyn’s perspective on managing this project will be published in 2017 on the C-EBLIP Blog.

Introduction

Research is to see what everybody else has seen, and to think what nobody else has thought.

Albert Szent-Gyorgy1

At this point in my university career, I have written several research papers, most of which were for the musicology courses I took as part of my music degree. This research gave me familiarity with the library catalogue, online databases for musicological articles, interlibrary loan, and contacting European collections to request material (this last one involved an interesting 4 a.m. phone call). As a Research Assistant, my background was helpful, but I found the depth of searching needed for the literature review much greater than anything I had done before.

My role as a research assistant for music librarian Carolyn Doi involved searching for sources, screening those sources based on their relevance to the project, and using NVivo software to identify themes in the literature.

Aim

The aim in doing the Literature Review was to find sources that discuss local music collections, especially those found in libraries. With these results, a survey to accumulate information on current practices for managing local music collections is under development.

It was important to find as many sources as possible, across a wide geographic area and collection types, although the majority came from North America. Reading sources from all over the world that talk about collections in a range of settings (e.g. libraries, churches, privately built, etc.) increased my understanding of the contexts that exist for local music collections.

Methodology

One of the most important parts of the Literature Review was to find as many items relating to local music collections as possible, or in other words – FIND ALL THE SOURCES!

2

2

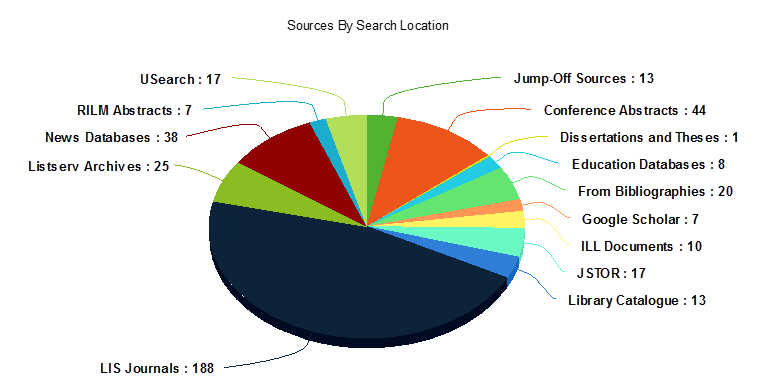

There were thirteen sources that became a jumping-off point, providing guidelines for how to focus the literature review. From here, I searched for literature in a variety of locations including USearch, Google Scholar, Library and Information Studies (LIS) databases, music databases, education databases, newspaper databases, humanities databases, and a database for dissertations and theses.

As a music student, I was familiar with the library catalogue and databases such as JSTOR. However, I was not familiar with the LIS or the Education databases. There were a variety of articles from journals, books, and newspapers that described different types and aspects of local music collections. One point of interest was the range of collection types, which appear in academic libraries and public libraries, to private and government archives. Most of the sources were case studies, which discussed the challenges and successes of a particular collection.

Other sources of information were print works from the University of Saskatchewan Library and Interlibrary Loan, conference abstracts and listserv conversations from the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML), the Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (CAML), and the Music Library Association (MLA).

After completing the search, 408 unique results were saved. Although many of the same sources appeared in different search locations, Figure 1 shows where documents were first located.

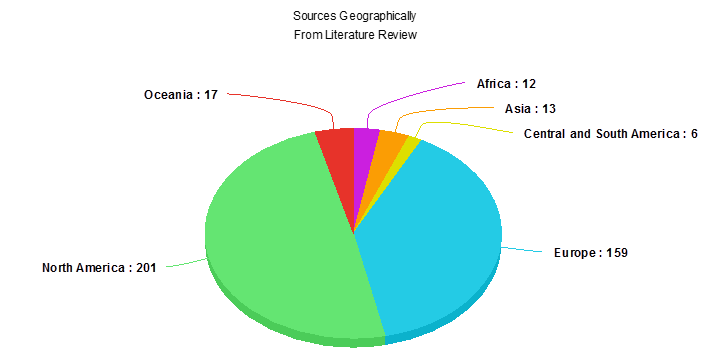

The majority of the sources came from North America and Europe. It is worth noting that this may be a result of the databases searched, rather than an indication of absence of local music collections and the study of such in other parts of the globe.

Figure 1: Pie chart showing all 408 saved documents based on search location.3

Challenges & Limitations

The common challenge, regardless of the database being searched, was finding effective search terms for finding relevant sources. It was important when searching in places like Google Scholar, JSTOR, and USearch to narrow the parameters considerably; otherwise one would obtain thousands of hits. Full-text searches, for example, were not helpful.

4

4

Comparatively, some of the LIS databases and ERIC, an education database, required only a keyword or two to find all of the information relative to local music collections that they contained.

Results

Figure 2: Geographical distribution of sources in the literature review.5

Figure 2: Geographical distribution of sources in the literature review.5

I saved 408 sources to Mendeley. These consisted primarily of journal articles describing case studies from a variety of international locations. Three hundred and sixty of the sources came from North America and Europe, with the complete breakdown by continent shown in Figure 2. Since we were more interested in research from North America, it is worth noting that 123 of the 201 North American sources are from the United States, 73 are Canadian, and 5 are from other countries such as Jamaica.

After screening, 59 documents were selected for NVivo content analysis. Documents were included if they spoke directly to the management of local music collections in public institutions. Documents were excluded if they were less relevant to the research topic (for instance, they may describe private collections), or they may be items that provide useful context (for example, this may be a resource on developing sound collections in a library).

Conclusions

For me, completing this literature review was a little bit like a treasure hunt – what could I do to find more information? Where else can I look? This process took me to locations for research that I did not even know existed, like the IAML listserv. And, after accidentally emailing every music librarian on the planet while trying to figure out how to work the thing, I was able to add a new researching tool to my repertoire.

In conclusion, the literature review served as a means for finding sources to analyze. However, it provided more than just a list of articles. The completion of the literature review, although global in scope, created a picture centered on North America, which has been an enormous help in understanding the topic of research. Through this search for documents, it has also been possible to see how it would be best to approach the analysis, based on the what work has already been accomplished and what work still needs to be done in this field.

1Szent-Gyorgyi, Albert. BrainyQuote. “Albert Szent-Gyorgyi Quotes.” Accessed July 22, 2016. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/a/albert_szentgyorgyi.html

2Imgflip. “Meme Generator.” Accessed May 30, 2016. https://imgflip.com/memegenerator

3Meta-chart. “Create a Pie Chart.” Accessed September 17, 2016. https://www.meta-chart.com/pie

4“Meme Generator.”

5“Create a Pie Chart.”

This article gives the views of the author and not necessarily the views of the Centre for Evidence Based Library and Information Practice or the University Library, University of Saskatchewan.