Overview

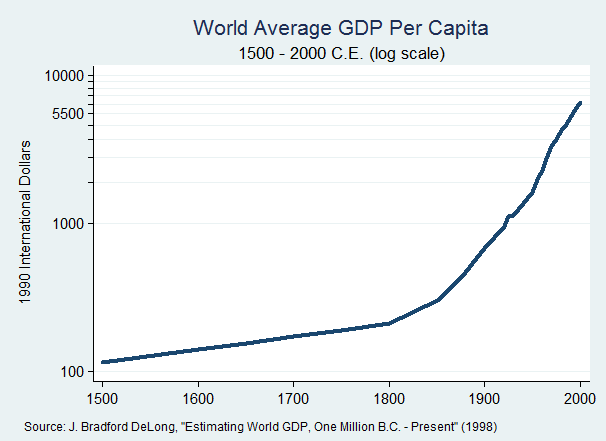

The greatest challenge to the contemporary narrative of globalization is the persistence of poverty and growing income inequality in the world. At the aggregate, the world is wealthier than ever before. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), between 1820 and 2010, the world’s average GDP per capita increased 10-fold and total real GDP grew 70-fold. In the same period, population only increased by 7-fold.

Figure 9-1: "World GDP Per Capita 1500 to 2000, Log Scale" Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWorld_GDP_Per_Capita_1500_to_2000%2C_Log_Scale.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Benjamin Daniels.

This means that the growth of wealth and production has outpaced population. In an equitable world, that would mean a reduction in both poverty and inequality. However in 1820, the richest countries were about five times as wealthy as the poorest countries. In 1950, the richest were 30 times as wealthy. In 2016, Qatar was the country with the highest GDP per capital which was 129 times higher than that of the lowest, the Central African Republic (CAR). Canada had the 24th highest GDP per capita which is still 70 times higher than that of the CAR. But this is only a between-country comparison, which can be misleading.

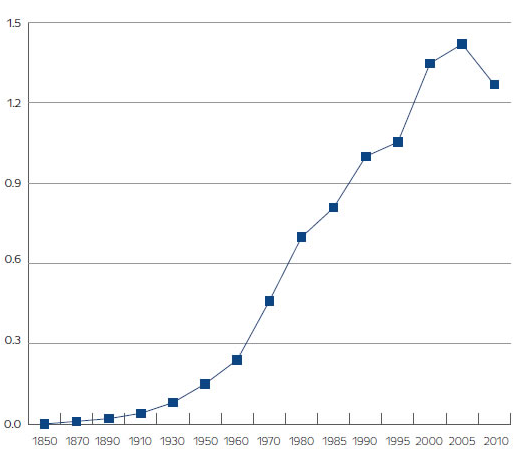

Figure 9-2: "Historic trends in within-country income inequality" Source: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1657-42062016000100003 Permission: CC BY 4.0 Courtesy of Universidad EAFIT.

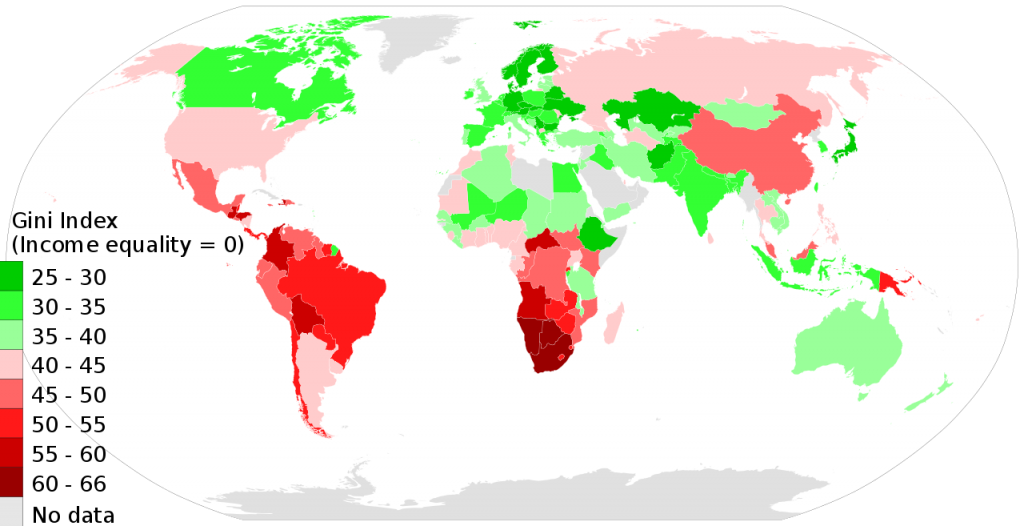

Hypothetically, a state may have a very high GDP but if that wealth is controlled by only one person, it would also have high poverty rates and great inequality. A common indicator of inequality rates is the gini coefficient: a representation of the income or wealth distribution of a nation's residents. A score of 1 equals complete inequality, where one person has all the countries wealth. A score of 0 equals perfect equality. In this image, green equals more equality and red equals more inequality.

Figure 9-3: "2014 Gini Index World Map, income inequality distribution by country per World Bank" Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3A2014_Gini_Index_World_Map%2C_income_inequality_distribution_by_country_per_World_Bank.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of M Tracy Hunter.

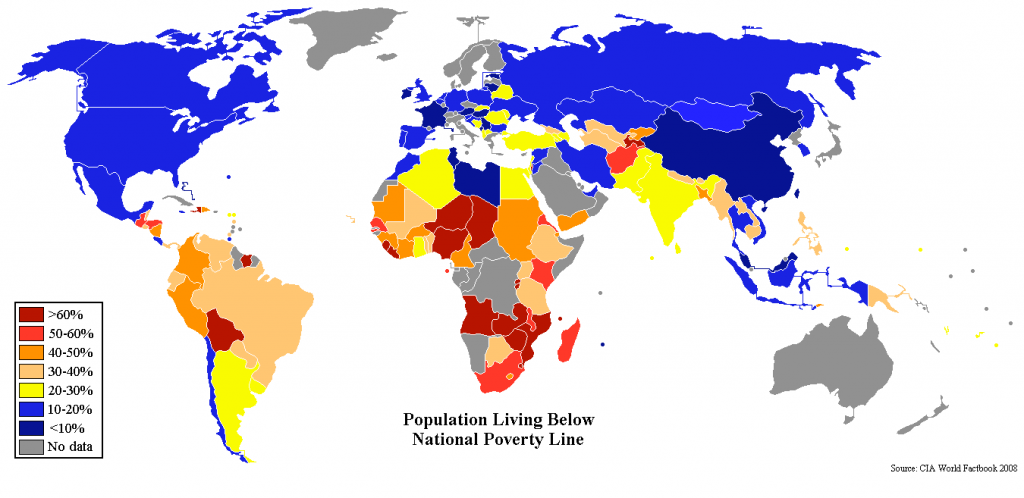

In the OECD states, inequality has historically demonstrated a ‘u-curve’, declining from the end of the 19th century to the 1970s and then once again increasing, dramatically so in the US and the UK. Breaking this down even further, women have disproportionately suffered under inequality of wealth as well as access to health care, personal security, and political rights. Since the end of the Second World War, the field of international development has sought to address the most egregious forms of poverty. And to a degree, there has been some success in reducing absolute poverty, defined as living under 1.90$ a day. Between 1990 and 2013, the number of people living in absolute poverty has been almost halved albeit not equally amongst all states. However, that still means that 767 million people are living on less than 1.90$ a day and half the world, approximately 3 billion people, are living on less than 2.50$ a day. These two maps from 2008 give us a glimpse on the importance of thinking about how we measure poverty. The first map shows us the percentage of people living under 1.25$ per day. The second shows us the percentage of people living under the poverty line established by their own country. While Egypt may have less than 2% living on less than 1.25$ per day, it also has 20-30% living under the national poverty line. Conversely, while Chine may have 6-20% living under 1$ per day, it has less than 10% living under the national poverty line.

Figure 9-4: "Percent poverty world map" Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APercent_poverty_world_map.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Sbw01f.

Further, income inequality has been rising within states, both developed and developing. The most striking statistic of global inequality is that the eight richest men own the same wealth as half the world’s population. This tension between the official narrative of economic globalization and the persistence of poverty and the increasing levels of inequality raises several questions. Why are poverty and inequality still such a prominent feature in the contemporary world? What can and should be done to ameliorate the worst excess of the contemporary globalized economy? And perhaps, even questions of personal complicity and moral obligation in addressing such issues. In this module we will look at the historical context of global poverty and inequality, the attempts of the development field to tackle these issues, and finally the connection between poverty and inequality to globalization.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the impact of colonialism on global poverty and inequality

- Debate the tensions within the field of international development on addressing global poverty and inequality

- Outline the MDGs, the SDGs, and how they are trying to address global poverty and inequality

- Read Arvanitakis and Hornsby, Chapter 10 in McGlinchey

- Take the Global Poverty Quiz: https://www.proprofs.com/quiz-school/story.php?title=ody5mta04hhg

- Take the Guardians Global Inequality Quiz: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jan/22/where-boss-likely-woman-global-inequality-quiz

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Watch the TEDx video “Africa Post-Colonial Development” by Fatoumata Waggeh https://youtu.be/s7lmz4UL4wE

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Watch the Ted Archive video “What is international development really?” by Alanna Shaikh https://youtu.be/R08tIdvs0AY

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Watch the “Sustainable Development Goals: Improve Life All Around The Globe” https://youtu.be/kGcrYkHwE80

- Watch the Ted Talks video “How We Can Make the World a Better Place by 2030” by Michael Green https://youtu.be/o08ykAqLOxk

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Complete the Discussion Questions

- Absolute poverty

- Agency

- Aid fatigue

- Battle for Seattle

- Colonialism

- Colonized

- Colonizer

- ‘Core’ states

- Corruption

- Decolonization

- Dependency theorists

- Developmental state

- Direct control

- Domestic opportunity cost

- GDP per capita

- Gini Coefficient

- Impact2030

- Income inequality

- Indirect control

- International development

- Keynesian economics

- Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

- Modernization theory

- Neo-liberalism

- Nepotism

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

- Periphery states

- Policy window

- Resource curse

- Social cleavages

- Social Darwinism

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Truman’s Point 4

- UN Global Compact

- Arvanitakis, James and David J. Hornsby, Chapter ten, “Global Poverty and Wealth” In International Relations, edited by Stephen McGlinchey, 113-122. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2017.

Learning Material

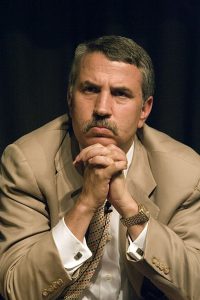

Figure 9-5: “Thomas Friedman” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AThomas_Friedman_2005_(4).jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Charles Haynes.

Thomas Friedman builds on this thesis in his book “The World is Flat: a Brief History of the 21st Century”. Friedman identifies 10 processes, events, and technological advancements that have flattened the global economy, providing actors in the developing world access to the benefits of economic globalization. These include: the collapse of the Berlin Wall, which plugged the former states of the Warsaw Pact into the global economy and shifted the narrative away from the Cold War and towards the triumphalism of capitalism; the wide spread adoption of the world wide web through Netscape which allowed everyone to participate in the burgeoning digital economy; and the processes of outsourcing, offshoring, and supply-chaining whereby companies could both achieve greater efficiency and global reach. Proponents of this narrative point to the decline in the number of people living under absolute poverty. They highlight the call centers and IT sector in Bangalore, India or high-tech success stories like Samsung in South Korea.

However, critics point to the fact that 767 million people are still living on less than 1.90$ a day and note that half the world, approximately 3 billion people, are living on less than 2.50$ a day. The majority of those people living in conditions of poverty are vulnerable groups and disproportionately women and children. Moreover, while not denying the vast generation of wealth economic globalization has produced, critics point to the unequal distribution of that wealth, both between states and within states. Perhaps the most damning critique is the acceleration of that inequality since the 1970s, when the ideology of neo-liberalism began its ascendancy. This persistence of poverty and the growth of inequality belies the founding principles of the field of international development, first formally laid out in ‘point 4’ of President Truman’s 1949 inaugural address. He argued,

Figure 9-6: “Harry Truman” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AHarryTruman.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Greta Kempton.

we must embark on a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas. More than half of the world’s population are living in conditions approaching misery. Their food is inadequate. They are victims of disease. Their economic life is primitive and stagnant. Their poverty is a handicap and a threat both to them and to more prosperous areas. For the first time in history, humanity possesses the knowledge and skill to relieve suffering of these people. The United States is pre-eminent among nations in the development of industrial and scientific techniques. The material resources which we can afford to use for assistance of other peoples are limited. But our imponderable resources in technical knowledge are constantly growing and are inexhaustible.

There are many aspects of this statement that are troubling. It is more than just a little pretentious. It is also presumptuous in its assertion that the West, and more specifically the US, is the epitome of development that all other states should emulate. However, it does make an important point: that it was possible in 1945 to try and end the worst cases of hunger, disease, and poverty; that the world had enough resources to do it then and it has even more resources to do it now. That to do so is not simply altruism but it may also prevent global instability and conflict. And yet, poverty is still here and inequality is growing. In order to understand the issue of global poverty and inequality, we will look at the historical constructs that have led to the present conditions of poverty and inequality, the field of international development, and the UN efforts embodied in the Millennium Development Goals and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Before moving on, let us assess your knowledge of global poverty and inequality

Take the Global Poverty Quiz: https://www.proprofs.com/quiz-school/story.php?title=ody5mta04hhg

Take the Guardians Global Inequality Quiz: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jan/22/where-boss-likely-woman-global-inequality-quiz

Post your scores anonymously on the polls below

[yop_poll id=”8″][yop_poll id=”9″]

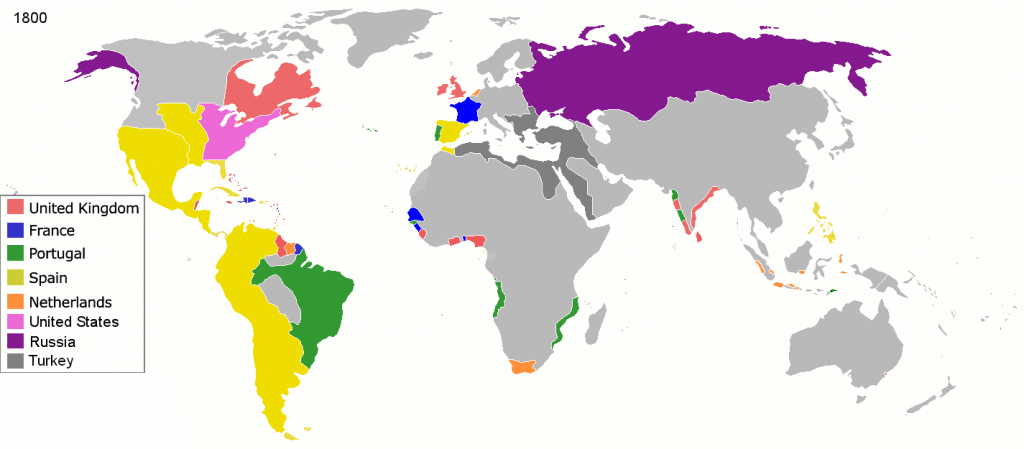

Figure 9-7: “Colonialism 1800” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AColonisation_1800.png Permission: Public Domain.

They would be joined, and for the most part eclipsed, by the French, English, and Dutch over the next several centuries. But instead of establishing trading posts, this later expansion would be a colonial exercise: the territorial conquest, occupation, and control of one country by another. This map shows which European country last controlled a particular colony.

Figure 9-8: “European Colonialism” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AEuropeanColonialism.png Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Davius.

There is some variance in the form of colonialism implemented, with some colonizers exerting direct control and others indirect control over the economic, political, and social structures of the colonized states. An example of direct control was the French colony of Algeria from 1830 to 1962. From the French government’s perspective, the Mediterranean region of Algeria was not a colony but was an integral part of France. This partly explains the sheer brutality and ferocity on both sides during the Algerian War of Independence fought between 1954-1962. This video gives the orientalist narrative of Algeria.

Figure 9-9: “10e Division parachutiste (Bataille d’Alger-1957)” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3A10e_Division_parachutiste_(Bataille_d’Alger-1957).jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Saber68.

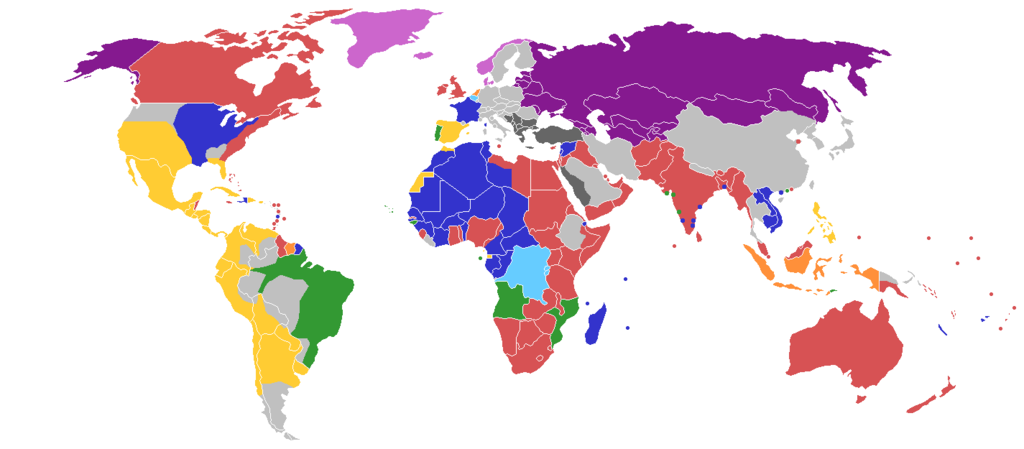

On the other hand, the British rule of the East Africa Protectorate, what we now call Kenya, typified indirect control. The British would control external affairs, the military, and taxes with all other state functions left to pre-colonial elites. Indirect rule would privilege a class or ethnic group who depended on the colonizing state for their wealth and positions. This divide and conquer strategy can partly explain ongoing instability and ethnic conflict in contemporary Kenya. This tension sparked over 1000 deaths during post-election violence in 2007-08. In Rwanda, Belgium employed this divide and conquer strategy creating the context for the 1994 Genocide whereby nearly 1 million Tutsis were massacred in 100 days.

Figure 9-10: “Post-Election Graffiti Source: https://flic.kr/p/74TPvC Permission: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Courtesy of ArtistSolo

Figure 9-11: “Rwanda Genocide” Source: https://flic.kr/p/7CwM1G Permission: by CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Steve Evans.

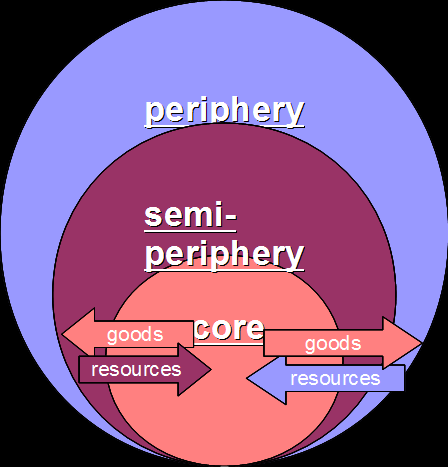

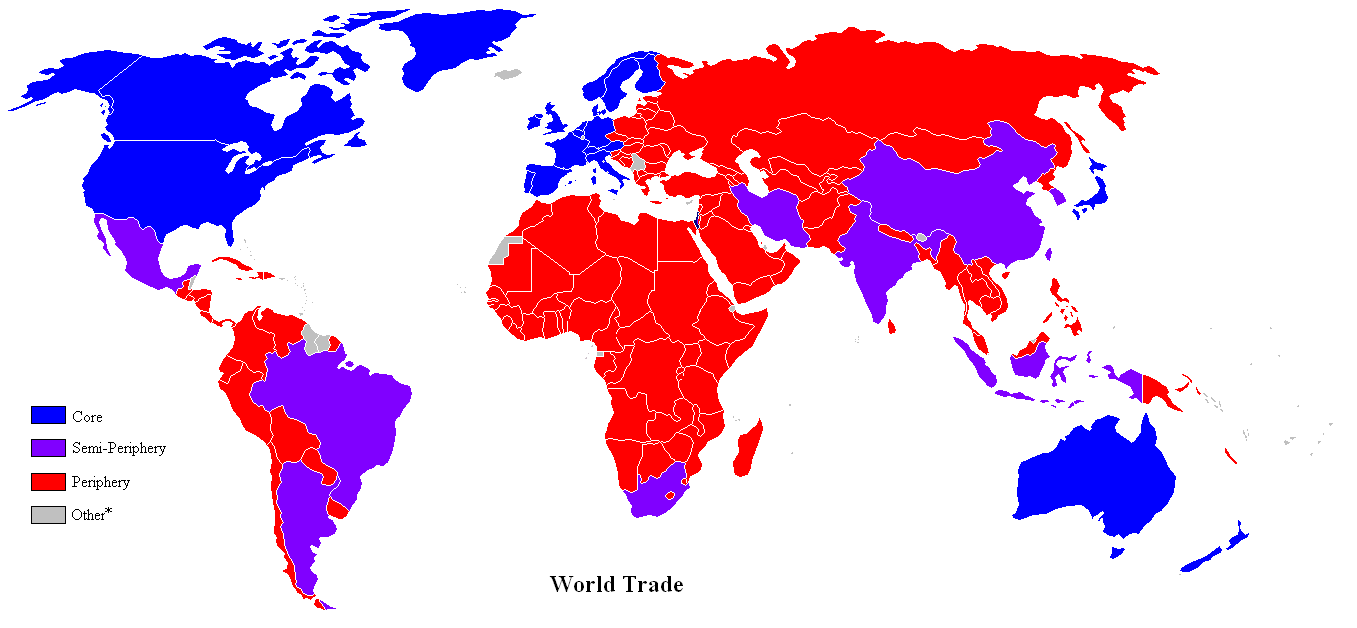

However, regardless of how a colony was controlled, all colonial possessions were perceived as sources of European wealth, power, and prestige. Importantly for a discussion of contemporary global poverty and inequality, most colonial experiences share some common features. First, the colonial enterprise was based on the violent imposition of one people over another and the subsequent subjugation of the colonized for the economic needs of the colonizer. Second, social and ethnic cleavages within the colonized state were manipulated or created in order to facilitate political, social, and economic control of colonial possessions. Third, the racist pseudo-ideology of ‘social Darwinism’ was used to legitimate the subordination and even decimation of other peoples and cultures in the name of a civilizing mission. These features had important ramifications on the political and economic condition of post-colonial states. Politically, the post-colonial states often suffered from two issues. First, in many states the social cleavages that were either exploited or created by colonizers left an unstable political landscape post-independence. Elections often become divided along ethnic or class lines, leading to the threat or actual use of violence during or after voting. This undermines the ability of the state to represent its citizens and their interests, leading to questions of legitimacy, and could create a repeating cycle of repression and protest. Second, post-colonial states often held on to the political structures established by the European colonizers. This often meant adopting the colonizers centralized and authoritarian administration which, in many ways, simply replaced European coercion with local coercion. Due to both the social cleavages and continuation of colonial governance structures, corruption and nepotism have also been endemic. Together, these factors limit the ability of many post-colonial states to provide stable governance and development. Economically, colonies had been oriented towards servicing their European masters. This often meant focusing on commodities and resources which could be used for manufacturing or be sold in the home market. Post-colonial economies often retained the economic structures created under colonialism. This has most clearly been iterated in Wallerstein’s ‘world system’ conceptualization of the world economy. He argues that the developed western states remain at the core of the global economy bringing in resources from the periphery in the global south. At the same time, the core states export higher values goods back toe the periphery, creating a structural cycle of dependency. If the global market has a sudden down turn, demand subsequently drops, leaving these states vulnerable.

Figure 9-12: ” World System Sphere” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWorld_system_sphere.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Piotrus.

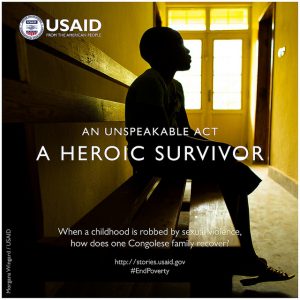

Figure 9-13: “An Unspeakable Act a Heroic Survivor” Source: https://flic.kr/p/w9hDFx Permission: CC BY NC 2.0 Courtesy of USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

For example, a persuasive argument has been made that the down turn in coffee prices was an important factor leading to the 1994 Rwandan Genocide; that economic pressure was placed on an unstable social and political framework, creating the conditions for these crimes against humanity. On the other hand, consistently high prices for a developing state’s natural resources can also create instability and repression. This is often called the ‘resource curse’. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one of the richest states in the world if you account for the resources in the ground. But after almost five centuries of colonial rule and subsequent ruthless authoritarian rule after independence, the DRC has one of the lowest scores UN Human Development Index scores in the world. This has been a story of brutal colonial rule, particularly under Belgian King Leopold I, followed by a severe authoritarian post-colonial rule under Mobutu. It is a story of corruption, war, child soldiers, and rape. There have been over 5 million people killed, millions more on the brink of starvation, and millions of women raped. Margot Wallstrom, the UN’s special representative on sexual violence in conflict, called the DRC the rape capital of the world. The atrocious state of the DRC can be traced back to its brutal colonial history and the willingness of the international community to abide by authoritarian rule as long as the resources continue to flow.

The colonial legacy of political, social, and economic instability has acted a massive obstacle to growth and development, leading to greater poverty and inequality. If a state is enmeshed in a cycle of protest and repression, brutal dictatorship, or outright civil war, there is little room for infrastructure development, economic growth, and poverty amelioration. If the government represents class or ethnic groups, there is little disincentive for nepotism and corruption. The colonial history of many developing states has left a lasting legacy of poverty and inequality.

Watch the TEDx video “Africa Post-Colonial Development” by Fatoumata Waggeh

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- What happened at the Berlin Conference in 1884?

- What role did colonialism historically play in Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo?

- How did the British use indirect rule in Nigeria?

- What was the impact of this indirect rule in post-colonial Nigeria?

- What role does oil play in this?

- What are Structural Adjustment Policies?

- What role did they play in Zambia?

- How has colonialism impacted development in Africa?

- What can be done now to break the cycle of poverty?

- What was the impact of this indirect rule in post-colonial Nigeria?

Whether we define international development as the process of increasing the economic wealth of the state or by other metrics of human development, it is by no means a new concept. Ideas and policies to achieve these outcomes have existed since time immemorial. However, international development as a field of study is relatively new, taking its current form following the Second World War. Three factors converged in this era to shape the emerging discipline. First, the great destruction wrought by the war required policies of reconstruction, first in Europe but subsequently extended to other parts of the world. Second, this was the era of decolonization. These newly decolonized states often lacked infrastructure and public services, providing opportunities for Western investment. Third, these newly decolonized states had also become the ideological, and at times the actual, battle ground between the US and the USSR in the Cold War. Each side sought to build allies and deny the same to the other side in the name of their ideological struggle. The result was the emergence of the field of development, albeit informed by a very specific set of ideas and taking very specific forms.

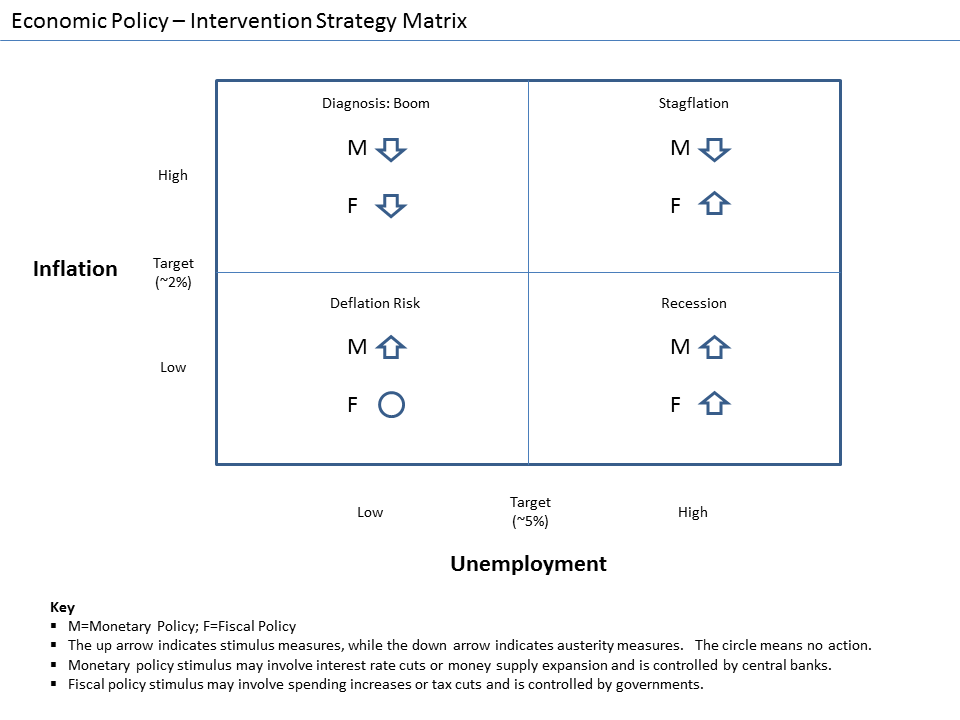

In the 1950s, Keynesian economics increasingly informed both domestic and international economic policy. The principal idea was that bust and boom cycles of market economies could be tamed by government intervention through monetary and fiscal policies. These economic levers can be used to cool down an economy that is experiencing high demand and inflation or to heat up an economy that is experiencing low demand and a potential recession.

Figure 9-14: “Economic Policy – Intervention Strategy Matrix” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AEconomic_Policy_-_Intervention_Strategy_Matrix.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Farcaster.

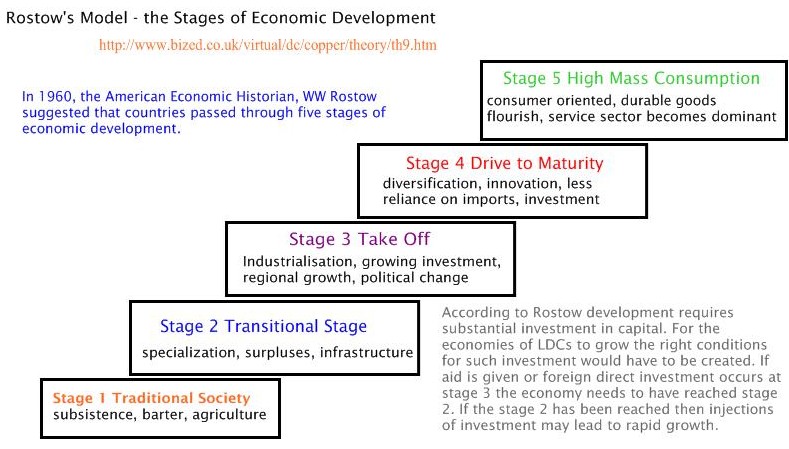

As applied to post-colonial states, it was believed that the principle obstacle to development was the lack of capital needed to kick start the process. The answer was government loans and development aid that could fill this gap. However, beyond an infusion of capital, there was not much theory specific to developing or post-colonial states. In the late 1950s, these Keynesian prescriptions were adapted by ‘modernization theory’ which sought to move post-colonial or ‘traditional societies’ through a series of stages, reaching ‘the age of mass high consumption’. These stages were modeled on the historical social, political, and economic phases of European development, seeking to build modern states with modern forms of government and modern economies.

Figure 9-15: “Rostow’s Model – The Stages of Economic Development” Source: http://welkerswikinomics.com/blog/2012/01/30/models-for-economic-growth-ib-economics/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND Courtesy of Jason G. Welker.

However, modernization theory failed to account for the trauma of colonialism and the context of global competition in which these states were seeking to develop their economies. When ‘development’ failed to materialize as expected, modernization policies became increasingly concerned with order and began to support more authoritarian governments. The desire to foster meaningful development was overshadowed by the Cold War needs of the West. By the 1960s, more critical voices sought to explain the apparent failure of the development project and the disproportionate benefit accrued to Western states. Dependency theorists argued the Global South was locked into dependent economic relationships with the West and, more specifically, with former colonizing states. It was argued that global capitalism had become the new colonialism. The states of the Global South were again the source of resources, cheap labour, and markets for value added goods from the Global North, creating a global poverty trap between the developed ‘core’ states and the developing ‘periphery’ states.

Figure 9-16: “World Trade Map” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWorld_trade_map.PNG Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Lou Coban.

Dependency theorists offered a range of solutions, from protecting infant industries to delinking from the capitalist system altogether. Connected but distinct from dependency theory are Marxist views of global capitalism as an extension of the class system to the global level. However, the prescriptions of both Marxist and dependency theorists, failed to actualize meaningful development. This was partly explained by the problem of inefficiencies generated by government policies which support domestic industries. When industry is protected it comes with a domestic opportunity cost; the subsidies and higher prices used to support domestic industry are resources that cannot be used in other ways, such as infrastructure development or investment in social services. It can also make domestic industries less competitive, making it difficult to phase out such government subsidies. Finally, since the 1970s, two schools of thought have emerged: neo-liberalism and the developmental state. As discussed in module 3, neo-liberalism has become the dominant economic model, arguing for a minimalist state and enhanced role for market forces. It was assumed that global welfare and poverty reduction was best achieved by the liberalization of trade, finance, and investment while at the same time deregulating the domestic economy to create a fertile ground for both domestic and international capital. And to a degree this argument has been arguably validated by the decrease in absolute poverty since the 1980s. However, it has also created instability leading to boom and bust economic cycles, first in Latin America (1980s), later in Asia (1997), and the global financial crisis (2008). And while rates of absolute poverty have declined, the 1.90$/day threshold is very low. Many argue a more meaningful threshold would be 3$ per day but that would put half the world back into poverty. Further, inequality both between states and within states has risen sharply. This “within state” inequality is found in developed and developing states. Globally, 70% of the world holds only 3% of the wealth and eight men hold half the world’s wealth. The ten richest billionaires hold more wealth than the state of Norway or the United Arab Emirates. The problem with inequality is that it becomes an obstacle to further growth. Just as an individual who is not in extreme poverty but still poor will have trouble saving money for retirement or for future mishaps, states whose GDP are above extreme poverty lines but still poor will be unable to invest in infrastructure, capital expenditures, and human capital. In both cases, they will hobble along but will be restricted from reaching their full potential.

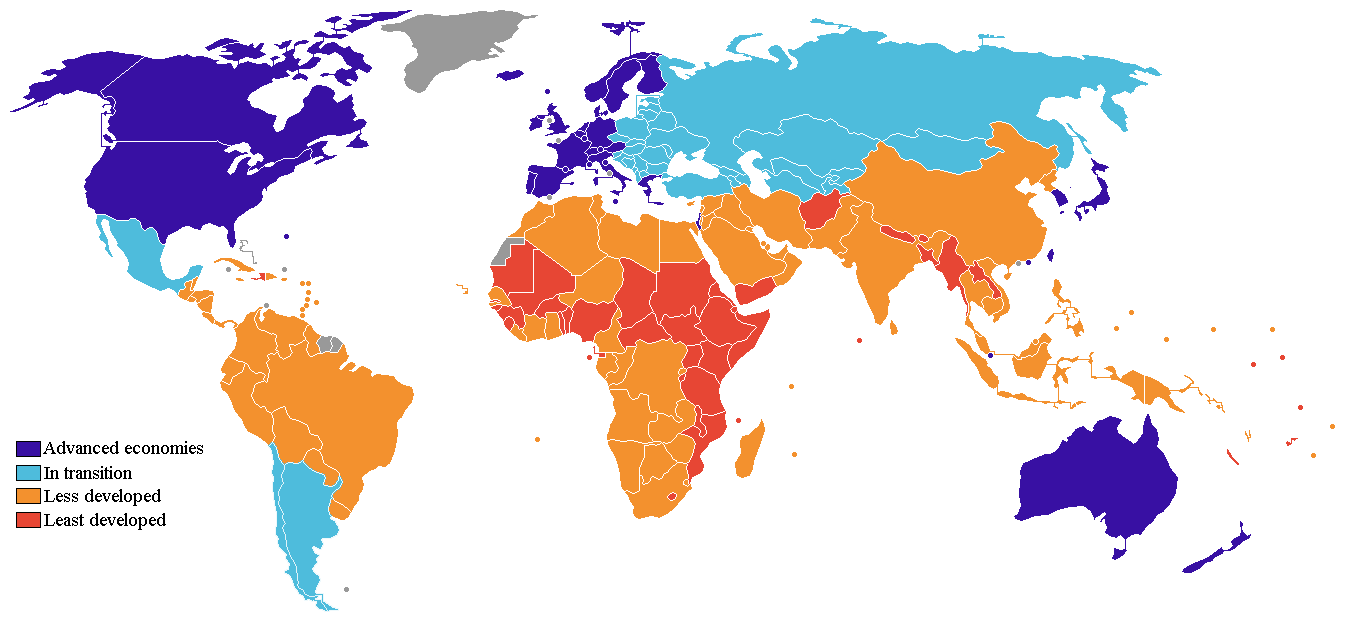

Figure 9-17: “Developed and Developing Countries” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Developed_and_developing_countries.PNG Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of Sbw01f.

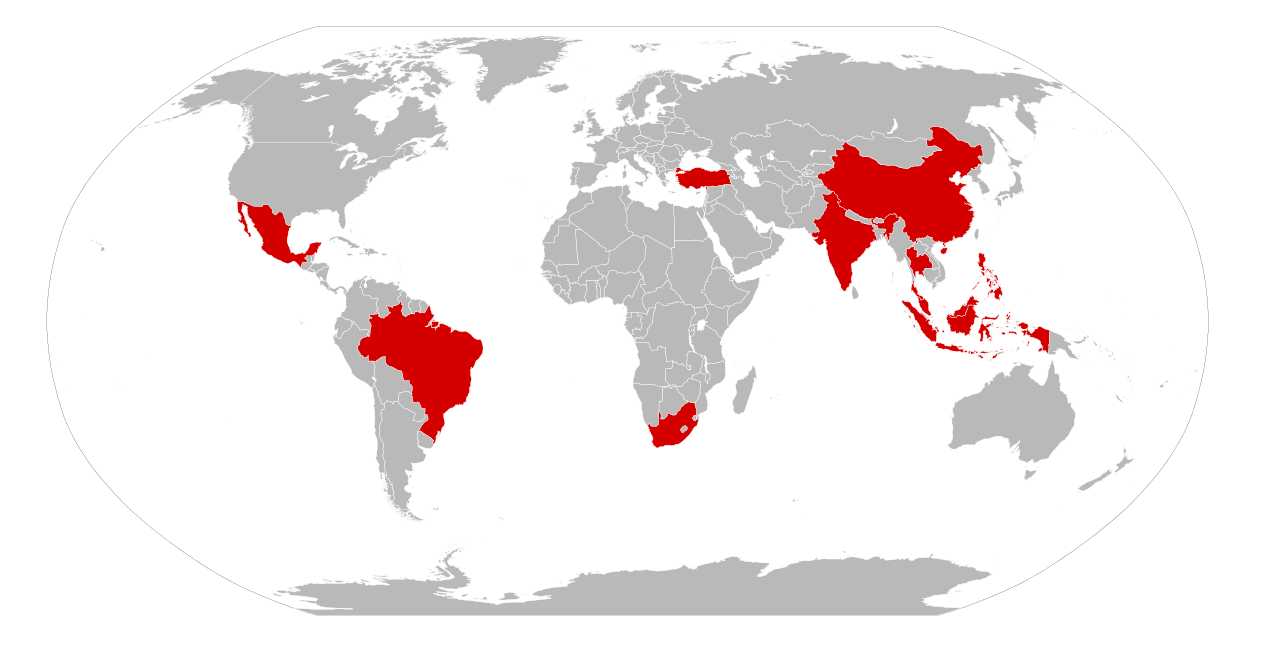

The second school of thought focused on the developmental state and contested the claims of neoliberal success. While neo-liberalism posits the free market as the path to development, those who advocate for the developmental state argue the opposite: that the state is necessary for meaningful development. From this perspective, the state needs to intervene in the economy in order to break the poverty trap identified by dependency theorists. The state guides investment and capital into sectors where the most gains can be made and where more technological advancement is possible. There are also critics of the developmental state. They argue overly intrusive government intervention can stifle innovation, entrepreneurship, and ultimately development itself. This map highlights the most important Newly Industrialized States which have adopted the developmental state model.

Figure 9-18: “Newly Industrialized Countries 2013” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ANewly_industrialized_countries_2013.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of RidwanFadilArif.

Taken together, these theoretical attempts to foster international development and attenuate global poverty represent a broad spectrum of ideologies and practices. For the Keynesians, the modernization theorists, dependency theorists, and the developmental state advocates, agency is key. They argue the state must be agential, playing a strong role in channeling capital, investment, and shaping policies towards the political, economic, and social development of the state. For neoliberals, the state is the problem and the impersonal discipline of the market is the solution. They argue the market will increase efficiency, attract capital, and develop economies through innovation and entrepreneurship. They also argue the market will punish state policy that runs counter to these processes. For some, GDP is the key measurement of development. For others, it is the well-being of the people that is the ultimate measurement of development. For others, inequality is a natural by-product of economic growth and is justified by declining levels of those living in absolute poverty. For others still, the rapid growth of inequality is deepening and hardening structural poverty. So what are we to make of this? First, we must be careful of essentialized narratives of ‘international development’, the ‘Global South’, and even the concept of poverty. For example, the 1.90$ per day metric of poverty is arrived at by quantitative assessments of living costs, but with reference to political considerations of institutions like the World Bank and programs like the Millennium Development Goals. Another example is the concept of the ‘Global South’ which is constituted by a wide variety of states with a wide variety of economic models; Venezuela, Rwanda, and Vietnam are very different cases. They have different economic strengths and weaknesses. Their histories are widely divergent. That means there may not be one cookie cutter approach to development that works for all cases and in all circumstances. Rather, development is a complex undertaking that is most often successful when it combines international resources and networks with localised knowledge and capacity building.

Watch the Ted Archive video “What is international development really?” by Alanna Shaikh

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- What is international development?

- How does this definitional issue inform our discussion of international development?

- What is international development about beyond aid?

- How is the developing world subsidizing us?

Figure 9-19: “Battle in Seattle, WTO protest” Source: https://flic.kr/p/5G9zVw Permission: CC BY- NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Mark Bult.

Figure 9-20: “Millennium Development Goals” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AMDGs.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of United Nations.

In this environment, two things opened a policy window for the MDGs. First, was simply the year 2000. Big dates make people consider big ideas. But big ideas need to come from somewhere and from someone who can convince others to pursue them. Second, it was UN Secretary General Kofi Annan who provided this leadership. Kofi Annan was at the height of his influence following on success in the human security projects of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ and the International Criminal Court. What the UN and Kofi Annan proposed was the goal of halving global poverty by 2015. It was to be a global effort with contributions from states in the Global North as well as the Global South. 189 states committed to the MDGs when they signed the millennium declaration at the UN Millennium Summit in 2000. The MDGs would mix global goals with country-level programs and assessments. For example, this meant balancing the global goal of child mortality with the particular circumstances of a state with very high HIV rates. The MDGs identified eight goals with specific dates and targets to achieve this goal of halving global poverty. Let’s look at and assess each in turn.

MDG One sought to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger. This is probably the most successful MDG, meeting its target of halving extreme poverty five years early. However, it narrowly missed it the goal of halving extreme hunger.

MDG Two sought to achieve universal primary education. By 2015, universal primary education was at 91%. While not meeting the goal, this is a significant improvement.

MDG Three sought to promote gender equality and empower women. This is a less specific goal but there have been important successes here. For example, two-thirds of developing countries achieved gender parity in primary education. In Southern Asia in 1990, only 74 girls were enrolled in primary school for every 100 boys. In 2015, there are 103 girls enrolled for every 100 boys.

MDG Four sought to reduce child mortality by two-thirds. There were significant gains here, with the under-5 mortality rate dropping from 90 deaths per 1,000 live births to 43 deaths per 1,000 live births. However, this is also a disheartening statistic since the most common causes of under-5 mortality rate are well-known and preventable. In 2015, this meant that 16,000 children a year died from mostly preventable causes.

MDG Five sought to improve maternal health. Again, while the maternal mortality was reduced by 44% between 1990 and 2015, it fell short of the two-thirds goal. And again, it is tragic when we confront the real world numbers, where the risk of maternal death is 1 in 3,300 for women in high-income countries but 1 in 41 for women in low-income countries often by preventable causes.

MDG Six sought to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases. Some progress has been made. The infection rate of HIV/AIDS has not been reversed but it has been significantly reduced with 1.8 million new HIV infections in 2015, down from 3.47 million in 1996. Referencing malaria, 6.2 million deaths have been averted between 2000 and 2015 with a 37% reduction in infection rate and a 58% reduction in mortality rate.

MDG Seven sought to ensure environmental sustainability. The goal of halving the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water was achieved, with 2.6 billion people now able to do so. Further, 2.1 billion people can access improved sanitation.

MDG Eight sought to develop a global partnership for development. In absolute numbers Official Development Aid increased 66% between 2000 and 2014, reaching 135.2 billion dollars. However, the financial crisis of 2008 has significantly slowed the resources made available by OECD countries. Further, a significant amount of the resources counted as ODA were committed towards debt reduction in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The MDGs have a mixed legacy. In pure absolute numbers, the MDGs were very successful: poverty was reduced, primary education increased, gender equality improved, child mortality rates declined, maternal health indicators raised, disease controlled, the environment bettered. The MDGs also addressed the issue of aid fatigue by introducing quantifiable measurements with set dates for completion. Prior to the 2000 Millennium Summit, international development was seen as ineffective, ODA was seen to benefit the donor state as much or more than the recipient, and poverty was seemingly endless. Now, development could be measured, assessed, and built upon. However, these very strengths are also a weakness. If you set targets and don’t meet them, have you failed? Even if significant improvements have been achieved? Further, part of the problem was that the MDGs were broad in scope with few intermediate steps between 2000 and 2015. These lessons would be incorporated in the successor to the MDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The SDGs were adopted in September 2015 at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in New York and will run to 2030. They have incorporated several important lessons learned from the MDGs. First, the SDGs are more inclusive than the MDGs. The MDGs were very top-down in orientation, with the goals set by the OECD and donor agencies. The SDGs on the other hand included middle and low-income states in the negotiation of its goals as well as consultation with civil society groups. These goals were applicable to states both in the Global North and the Global South. Further, the SDGs are holistic and try to balance poverty reduction, inequality, and sustainability with economic growth and job creation. Second, the SDGs have actively sought to include the private sector through the UN Global Compact and Impact2030. The UN Global Compact seeks to mobilize a movement of sustainable companies in support of the SDGs. The Impact2030 is a private sector-led initiative to activate human capital investments to aid in the achievement of the SDGs. Third, the SDGs draw more upon human rights than the MDGs. Rather than focus exclusively on economic capital and GDP growth as the means to development, the SDGs include an investment in human capital and making a commitment to achieving a universal, people-oriented, equitable, and just society. Fourth, the SDGs explicitly recognize and seek to improve the conditions of visible minorities and vulnerable groups. This is meant to make development inclusive of all members of society. Fifth, the SDGs seek to include civil society actors in local projects and with local partnerships. In this way, the SDGs are again more grassroots in their orientation than the MDGs. Finally, the SDGs are much more robust and detailed than the MDGs, including 169 targets embedded in 17 goals.

Figure 9-21: “Sustainable Development Goals” Source: https://en.unesco.org/sdgs Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

SDG One seeks to end poverty in all its forms everywhere

SDG Two seeks to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture

SDG Three seeks to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

SDG Four seeks to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

SDG Five seeks to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

SDG Six seeks to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all

SDG Seven seeks to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all

SDG Eight seeks to promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

SDG Nine seeks to build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation

SDG Ten seeks to reduce inequality within and among countries

SDG Eleven seeks to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable

SDG Twelve seeks to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

SDG Thirteen seeks urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts*

SDG Fourteen seeks to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development

SDG Fifteen seeks to protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss

SDG Sixteen seeks to promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

SDG Seventeen seeks to strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.

These are ambitious goals but if achieved, even if only in part, they will make a significant impact on addressing the issues of global poverty and inequality. Since the SDGs were only adopted in September of 2015, it is still too early to judge their effectiveness. And there are three important challenges to their implementation. First, the SDGs are very integrated and intersectional. This means that addressing hunger, for example, means coordinating with health, education, and economic growth. This does allow them to address issues more holistically but is also makes their implementation much more complicated. Second, measurement of the SDGs is crucial to ensuring progress in their implementation. However, two years into the SDGs, there has been a lack of generally accepted indicators of progress by which to make comparisons across states. Third, both in the developed and developing world, there has been a lack of awareness of the SDGs. While the MDGs were new and created waves in the international community, the SDGs have had less fanfare. This creates problems of stymying grassroot initiatives and global support for the SDGs. The MDGs and the SDGs are probably the most holistic and comprehensive attempt to deal with global poverty and inequality. The MDGs have achieved notable successes and the SDGs have sought to build on their successes and avoid their weaknesses. Only time will tell if they will be successful in doing so.

Watch the “Sustainable Development Goals: Improve Life All Around The Globe”

Watch the Ted Talks video “How We Can Make the World a Better Place by 2030” by Michael Green

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- What are the SDGs?

- How do they reflect who we want to be?

- What is the Social Progress Index?

- Why was GDP growth useful to tackle poverty but not the SDGs?

- What does the variance on the regression line between the SPI and GDP tell us?

- What is the people’s report card?

- So, is the accomplishment of the SDGs possible? Likely?

- If so, how? If not, why not?

It has been quantifiably demonstrated that the world has grown increasingly wealthy and more economically integrated over the last two hundred years. Moreover, the world has become exponentially more productive since the end of the Second World War. Since 1990, we have also witnessed the number of people living under extreme poverty halved. These are important gains. However, while the number of people living under extreme poverty has been halved, half the world still lives on less than 3$ a day. And eight men own the aggregate wealth of 3.5 billion people. Inequality has also risen both between states and within states. Within state inequality has grown in both the Global South and the Global North. Poverty and inequality in the Global South often share a legacy of colonialism which created social, political, and economic cleavages, leading to instability and at times violence. Colonial borders do not match ethnic groupings, leading to unstable social structures, often accompanied by scapegoating. Colonial political structures have often been co-opted by the post-colonial governments, leading to a continuation of authoritarian and coercive rule, often with ethnic implications. Colonial economic structures are often continued in post-colonial states, retaining dependence on the economies of the former colonizing state, fostering a neo-colonial relationship. This colonial legacy has created serious obstacles for development. The field of international development came to maturity following the Second World War. It has sought over time to reduce poverty, enable good governance, and increase human well being. However, most development theories essentialize the Global South, applying a one-size-fits-all approach, most often defined by donors and states in the global north. Successes and failures have led to shifting prescriptions from a prioritization of the state to the prioritization of markets, from a focus on GDP growth to a focus on human well being; none of which has provided the magic cure for poverty and inequality. However since 2000, the MDGs and the subsequent SDGs do provide some suggestions for going forward. First, the effort needs to be global, including international organizations, states of the Global South and the Global North. Second, there needs to be sustainable solutions that balance economic growth and human well being, poverty reduction and inequality reduction, economic activity and environmental protection. However, for the MDGs and the SDGs to be successful, it will need to be a global effort – something that can be difficult, especially when facing global economic and political instability.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Absolute poverty: the condition where a person does not have the minimum amount of income needed to meet the minimum requirements for one or more basic living needs over an extended period of time, currently defined as living under 1.90$ a day

Agency: the capacity, condition, or state of acting or of exerting power

Aid fatigue: the drop in foreign aid linked to growing cynicism with corruption and inefficiencies in recipient countries

Battle for Seattle: a series of marches, direct actions, and protests carried out from November 28 through December 3, 1999, that disrupted the World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Conference in Seattle, Washington; often viewed as the beginning of the anti-globalization movement

Colonialism: the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically

Colonized: subjected to the rule of another country

Colonizer: a person or a group who helps establish or form a colony

‘Core’ states: dominant industrialized capitalist countries that exploit the peripheral states

Corruption: dishonest or illegal behavior especially by powerful people such as government officials

Decolonization: the process in which a country that was previously a colony becomes politically independent

Dependency theorists: view there is a dominant world capitalist system that relies on a division of labour between the rich 'core' states and poor 'peripheral' states. Over time, the core countries will exploit their dominance over an increasingly marginalised periphery

Developmental state: a model of capitalism that advocates for the state to have more independent, or autonomous, political power, as well as more control over the economy. A developmental state is characterized by having strong state intervention, as well as extensive regulation and planning

Direct control: a territory or piece of land governed directly by a foreign power. The governing power may exercise direct rule through soldiers and officials, forcing the locals into submission

Domestic opportunity cost: benefit, profit, or value of something that must be given up to acquire or achieve something else

GDP per capita: a measure of a country's economic output that accounts for population. It divides the country's gross domestic product by its total population

Gini Coefficient: a representation of the income or wealth distribution of a nation's residents. A score of 1 equals complete inequality, where one person has all the countries wealth. A score of 0 equals perfect equality.

Impact2030: a private sector-led initiative to activate human capital investments to aid in the achievement of the SDGs

Income inequality: the unequal distribution of household or individual income across the various participants in an economy

Indirect control: a system of government used by the British and French to control parts of their colonial empires, particularly in Africa and Asia, through pre-existing local power structures

International development: encompasses a broad range of disciplines and endeavors

to improve the quality of life of people around the world. It includes both economic and social development, encompasses many issues such as humanitarian and foreign aid, poverty alleviation, the rule of law and governance, food and water security, capacity building, healthcare and education, women and children’s rights, disaster preparedness, infrastructure, and sustainability

Keynesian economics: that optimal economic performance can be achieved, and economic slumps prevented, by influencing aggregate demand through activist stabilization and economic intervention policies by the government.

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs): eight goals, all with the target date of 2015, that form a blueprint agreed to by all the world’s countries and all the world’s leading development institutions to meet the needs of the world’s poorest.

Modernization theory: used to explain the process of modernization that a nation goes through as it transitions from a traditional society to a modern on

Neo-liberalism: a policy model of social studies and economics that transfers control of economic factors to the private sector from the public sector. It takes from the basic principles of neoclassical economics, suggesting that governments must limit subsidies, make reforms to tax law in order to expand the tax base, reduce deficit spending, limit protectionism, and open markets up to trade. It also seeks to abolish fixed exchange rates, back deregulation, permit private property, and privatize businesses run by the state.

Nepotism: the practice among those with power or influence of favoring relatives or friends, especially by giving them jobs.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): an intergovernmental economic organisation founded in 1960 to stimulate economic progress and world trade

Periphery states: underdeveloped industrially, these states are dependent on ‘core’ states for capital

Policy window: a window of opportunity which facilitates policy change

Resource curse: a paradoxical situation in which countries with an abundance of non-renewable resources experience stagnant growth or even economic contraction. The resource curse occurs as a country begins to focus all of its energies on a single industry, such as mining, and neglects other major sectors

Social cleavages: the division of voters into groups known as voting blocs based on political issues. Voters are considered either adversaries or advocates of each issue

Social Darwinism: the theory that individuals, groups, and peoples are subject to the same Darwinian laws of natural selection as plants and animals. Now largely discredited, social Darwinism was advocated by Herbert Spencer and others in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and was used to justify political conservatism, imperialism, and racism and to discourage intervention and reform

Sustainable Development Goals: a new, universal set of goals, targets and indicators that UN member states will be expected to use to frame their agendas and political policies over the next 15 years.

Truman’s Point 4: U.S. policy of technical assistance and economic aid to underdeveloped countries, so named because it was the fourth point of President Harry S. Truman’s 1949 inaugural address

UN Global Compact: a United Nations initiative to encourage businesses worldwide to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies, and to report on their implementation.

References

17Goals. 2017. “Learn About the SDGs.” 17Goals.org. Accessed November 25, 2017 www.17goals.org

Bates, Francesca. 19 January 2015. “British Rule in Kenya.” Washington State University. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://history.libraries.wsu.edu/spring2015/2015/01/19/british-rule-in-kenya/

Berger, Nahuel. 23 June 2014. “Theorist Eric Maskin: Globalization Is Increasing Inequality.” World Bank. Accessed November 25, 2017 http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/06/23/theorist-eric-maskin-globalization-is-increasing-inequality

Clarke, Joe Sandler. 26 September 2015. “7 Reasons the SDGs will be Better than the MDGs.” The Guardian. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/sep/26/7-reasons-sdgs-will-be-better-than-the-mdgs

Dugarova, Esuna and Nergis Gülasan. 2017. “Global Trends: Challenges and Opportunities in the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals.” United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Accessed November 25, 2017 http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/SDGs/English/Global%20Trends_UNDP%20and%20UNRISD_FINAL.pdf

Ferreira, Francisco. 10 April 2015. “The International Poverty Line has Just Been Raised to $1.90 a Day, But Global Poverty is Basically Unchanged. How is that Possible?” World Bank. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/international-poverty-line-has-just-been-raised-190-day-global-poverty-basically-unchanged-how-even

“Global HIV and AIDS Statistics.” 1 September 2017. Avert. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://www.avert.org/global-hiv-and-aids-statistics

Green, Duncan and Takumo Yamada. 21 October 2015. “How Will the SDGs Differ from the MDGs?” Oxfam. Accessed November 25, 2017 http://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/how-will-the-sdgs-differ-from-the-mdgs/

Gregson, Jonathan. “The World’s Richest and Poorest Countries.” 13 February 2017. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/economic-data/worlds-richest-and-poorest-countries

Inequality.org. 2017. “Global Inequality.” Institute for Policy Studies. Accessed November 23, 2017 https://inequality.org/facts/global-inequality/

McArthur, John W. Summer-Fall 2014. “The Origins of the Millennium Development Goals.” SAIS Review 34 (no.2): 5-24.

Ratcliff, Anna. 16 January 2017. “Just 8 Men Own Same Wealth as Half the World.” Oxfam. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://www.oxfam.org/en/pressroom/pressreleases/2017-01-16/just-8-men-own-same-wealth-half-world

Rodrik, Dani. 14 November 2017. “The Fatal Flaw of Neoliberalism: It’s Bad Economics.” The Guardian. Accessed November 22, 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/nov/14/the-fatal-flaw-of-neoliberalism-its-bad-economics?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Facebook

Risse, Nathalie. 25 April 2017. “Getting Up to Speed to Implement the SDGs: Facing the Challenges.” International Institute for Sustainable Development. Accessed November 25, 2017 www.sdg.iisd.org/commentary/policy-briefs/getting-up-to-speed-to-implement-the-sdgs-facing-the-challenges/

Roser, Max. “HIV/AIDS.” Our World in Data. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://ourworldindata.org/hiv-aids/

Roser, Max and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina. 2017. “Global Extreme Poverty.” Our World in Data. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://ourworldindata.org/extreme-poverty/

Shah, Anup. 22 August 2010. “A Primer on Neoliberalism.” Global Issues. Accessed November 23, 2017 http://www.globalissues.org/article/39/a-primer-on-neoliberalism

Snow, Dan. 9 October 2013. “DR Congo: Cursed by its Natural Wealth.” BBC Magazine. Accessed November 25, 2017 http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24396390

“UN Official Calls DR Congo ‘Rape Capital of the World.’” 28 April 2010. BBC News. Accessed November 25, 2017 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/8650112.stm

United Nations. 2010. “Report on the World Social Situation 2010: Rethinking Poverty.” United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Accessed November 25, 2017 http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/rwss/docs/2010/chapter2.pdf

United Nations. 2015. “Background.” We Can End Poverty: Millennium Development Goals and Beyond 2015, United Nations. Accessed November 25, 2017 http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/bkgd.shtml

van Zanden, J., Joerg Baten, Marco Mira d’Ercole, Auke Rijpma, Marcel Timmer (eds.) 2014. “How Was Life?: Global Well-being since 1820.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264214262-en

Williams, Jeremy. 2 February 2017. “How Many People Still Live in Poverty?” Make Wealth History. Accessed November 25, 2017 https://makewealthhistory.org/2017/02/02/how-many-people-still-live-in-poverty/

Supplementary Resources

- Wisor, Scott. Measuring Global Poverty: Toward a Pro-Poor Approach. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011.

- Milanovic, Branko. Global Inequality and the Global Inequality Extraction Ratio: The Story of the Past Two Centuries. Washington: World Bank Group, 2009

- Kanie, Norichika and Biermann, Frank. Ed. Governing Through Goals: sustainable development goals as governance innovation. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017