Developed by Anna Hunter. Revised by Nicole Wegner, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan.

Overview

This module will introduce students to the concept of colonialism and its historical and present effects. Despite the removal of many institutionalized colonial systems, the consequences of these systems still have profound effects on Canada’s Indigenous population. Historically, spiritual, social, political, and economic ways of Indigenous life were controlled by federal and provincial governments, and this module will explore the ways that this has affected Indigenous identities.

- Examine the concept of colonialism.

- Explain key features of the legacy of colonialism in Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

- Assess how colonialism in its various political, economic, cultural, social, and spiritual contexts has affected Indigenous identity.

- Read the module Learning Material.

- Read the Required Readings.

- Complete the optional Learning Activities. These will not be graded but will enhance your understanding of the course material.

- Complete the Self-Test and check your answers with those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Complete a Reflective Learning Journal Entry for this module within Canvas. This is a graded component.

- Check the syllabus for any other formal evaluations due.

- Colonialism

- Classical Colonialism

- Neo-Colonialism

- Cognitive Imperialism

- Assimilation

- Residential School System

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Ladner, Kiera L., and Michael McCrossan. “Whose Shared History?.” Labour/Le Travail 73, no. 1 (2014): 200-202. [PDF in Canvas]

- Alfred, Taiaiake, and Jeff Corntassel. “Being Indigenous: Resurgences against contemporary colonialism.” Government and Opposition 40, no. 4 (2005): 597-614. [Library link in Canvas]

- Palmater, Pamela. “Genocide, Indian policy, and Legislated Elimination of Indians in Canada.” Aboriginal Policy Studies 3, no. 3 (2014): 27-54. [PDF in Canvas]

Learning Material

Understanding colonialism is key to understanding Indigenous political issues in Canada. As Indigenous political identity, culture, economics, and spirituality have all been strongly influenced by the history of colonialism between Indigenous groups and European colonizers, this history is crucial in understanding the modern political relationships between the federal government and Indigenous groups in Canada.

What is colonialism?

Colonialism is the policy by which a nation seeks to extend its control and authority over foreign territories. James Frideres conceptualizes the colonization process into seven parts:

- The incursion of the colonizing group into a geographical area.

- The destruction of the social and cultural structures of the Indigenous group.

- The establishment of systems of external political control.

- The establishment of systems of Indigenous economic dependence.

- The provision of low quality social services for the colonized people.

- The impartation of an ideology of racism and a colour line to regulate social interaction between groups.

- The emerging of an ideology of biological superiority and inferiority to justify the exploitation of Indigenous peoples and break down their resistance to exploitation (Wotherspoon and Satzewich 2000, 8).

Classical colonialism refers to the various policies and practices of the last four hundred years by which the primary colonizing nations of Spain, England, France, Portugal and Holland asserted a western hegemony and superiority over the New World primarily for economic profit and religious motivations (Williams 1990).

Neo-colonialism refers to recent formulations and functions of political and economic globalization that have continued the exclusion and marginalization of Indigenous peoples and their participation from sites of power and decision-making. These practices are not always overt, but an example is the large absence of Indigenous representatives in political decision-making positions within Canada, as well as the lack of control of political issues by Indigenous groups themselves.

For each of the following, choose whether the statement is reflective of “Classical Colonialism” or “Neo-Colonialism” or “Both”.

The current situation of Indigenous peoples and their governments in Canada is difficult to understand, and redress, without locating and situating the colonial legacy of this relationship. Indigenous peoples from around the world have been affected by colonialism, and these experiences that provide the theoretical framework necessary to conceptualize the highly marginalized and disadvantaged position of Indigenous peoples within the dominant institutional framework of Canadian life (Wotherspoon and Satzewich 2000,14). Indigenous peoples and their governments have historically asserted a wide variety of strategies of resistance to their domination and marginalization. Duane Champagne reminds us that “the geopolitical, economic, and cultural dimensions of colonized communities create the situational context that informs actors and communities in specific historical situations” (Champagne 1996, 6). Most recently, Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples around the world are increasingly advocating and adhering to post-colonial visions and practices. As a result of these mobilizations, progressive and positive changes are becoming increasingly noticeable in a variety of different domestic and international forums around the world, including international and domestic courts, arts and cultural organizations, and even university classrooms and curriculums.

Peter Kulchyski uses the term “totalization” to explain the magnitude of colonial impacts: “Totalization has been experienced by Indigenous peoples as a State policy, characterized by many scholars as ‘assimilation,’ which has worked to absorb them into the established order” (Kulchyski 2005, 23). Government policies have been complemented and compounded by the actions of a wide array of non-governmental authorities, including educators, media personnel, lawyers and judges, literary authors and publishers, geographers, historians, and scientists.

Ultimately, colonialism is now reflected in the “cognitive imperialism” of the dominant institutions, policies, histories and literatures of the occupying powers (Battiste 2000, xix; LaRoque 1997, 11). An example of cognitive imperialism is the conscious and unconscious ways that Indigenous ways of life and knowledge(s) are often believed to be inferior to Westernized practices. These unequal power configurations have resulted in the progressive deterioration and marginalization of Indigenous peoples and their institutions, a situation that continues to be socially reproduced through a wide range of externalized and internalized colonial actions. Externalized colonial effects include the many different forms of domination that have been unilaterally imposed over the years such as residential schools, the “Sixties Scoop,” and the Indian Act. Internalized colonial effects refer to the power differentials and imbalances within Indigenous communities themselves that have led to deep-rooted issues of accountability, fairness and bias in terms of access to programs and services, leadership selection and gender discrimination.

The Legacy of Colonialism in the Canadian Context: “Civilizing the Indian”

In Canada, the colonial agenda has consistently been directed towards the control and assimilation of its original inhabitants. Indians, a term historically used to describe Canada’s original Indigenous occupants, were believed to be uncivilized and lacking basic entitlements to property and citizenship rights, and policy was directed to reversing this trend through the often-stated goal of “civilizing the Indians.” This civilizing goal was made clear in the Annual Report of the Department of the Interior, 1876 which includes the following statement:

This goal of civilization is confirmed by the following assertion by John A. Macdonald, recorded in 1887: “The great aim of our civilization has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the inhabitants of the Dominion, as speedily as they are fit for the change” (Sessional Papers 1887, 37). The resulting programs and policies of assimilation and civilization of First Nations peoples have continued through a variety of different forms of legislated intrusions and interventions.

Jane Dickson-Gilmore explains that while historically colonial states existed in uneasy alliances with First Nations, the need for those alliances diminished when the move to a welfare approach was undertaken. The move towards intrusive legal interventionism was swift (Dickson-Gilmore 2002, 317). Although during the time of confederation the Canadian government officials had relied heavily on military alliances with Indigenous peoples in order to secure Canadian sovereignty against the assertions of other nations, once territorial integrity was intact the Canadian government sought to secure settlement expansion and resource development initiatives. In order to accomplish these goals, the Canadian government implemented a gradual acculturation process based on a set of inter-related policies that included treaty making, land cessions, annuities, reserves, schools and Indian agents. These policies of gradual acculturation eventually gave way to the enfranchisement policy that attempted rapid assimilation of the Indians. The government shifted approaches towards an oppressive policy program of control using political, economic, cultural, spiritual, and social channels.

Political and Economic Policies

The federal government sought political and economic control through the undermining of traditional tribal political and governing systems. The federal government forced a new political and economic system on the First Nations through the 1876 Indian Act, the first consolidation of laws pertaining to Indians. Under the Indian Act regime, colonial governments assumed control of key features of governing First Nations peoples, including entitlement to membership and Indian status, leadership selection, and land tenure in First Nations’ communities. Through the Indian Act, the federal government also assumed control of determining who had access to Indian land property rights.

The pass system allowed Indian agents to control which Indigenous persons had access rights beyond the lands reserved for Indians. The pass system, implemented between 1882 and 1928, was an institutional practice whereby an “Indian” wishing to leave reserve lands would require a pass stipulating the time duration and purpose of leave. The pass would need to be signed by a government Indian agent and those in violation of this system would be taken into custody by the police and returned to their reserve lands.

In addition to policies that restricted and closely monitored Indigenous mobility, there was the creation of reserve policies that dispossessed First Nations peoples from their traditional territories and resources, obliging Indigenous participation in the Canadian agricultural and industrial economy. However, the inadequate land base offered through the reserve system could not sustain their populations, and the Westernized governing systems did not function effectively in Indian communities.

Imagine a modern-day pass system that required you to get signed permission to leave the city you lived in (e.g., needing to apply for permission to leave Saskatoon city limits).

Do you believe this system would violate your constitutional rights and freedoms?

Complete the class poll shown below by voting “yes” or “no”.

[poll response link]You can see the results of the class poll below:

[live results link]Cultural Policies: Spiritual

The federal government advanced its agenda of cultural and spiritual control through a series of civilization policies combined with Christian missionary conversion activities. Cultural and spiritual control involved the imposition of western European religious ideologies combined with the subjugation of Indian cultural and spiritual systems and practices. Through colonization, Westernized knowledge has undervalued Indigenous spiritual and cultural beliefs. Moreover, legislative power was often used in the name of protecting Indians by assimilating them into Euro-Canadian ways (Miller 1991,194). For example, the Indian Act prohibited and criminalized traditional spiritual ceremonies like the Sun Dance and Thirst Dance of the southern prairies and the Potlatch of the west coast from 1884-1951. The result of these practices was the devaluation of traditional cultural and spiritual practices.

Examine the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms before addressing the following question.

Cultural Policies: Social

Finally, the federal government instituted a regime of social control designed to assimilate First Nations peoples into European norms and values. One of the most important avenues of social control over Indians concerned kinship and family structures. The federal government has a long history of disrupting family and kinship structures, beginning with the imposed colonial systems that disrupted pre-contact gender roles that had previously enabled and empowered female authority and leadership. J. R. Miller notes the inherent contradictions of this approach in the following passage:

The Indian Act continued to trace Indian descent and identity through male lineage until legislated changes in 1985. These changes eliminated the gender discrimination of Indian women losing their Indian status if they married a non-Indian man, while non-Indian women gained status if they married a man with Indian status. This problematic aspect of the Indian Act will be explored in greater detail in Module 5.

Another formidable form of social control involves the long line of assimilationist Indigenous child welfare policies (Wotherspoon and Satzewich, 2000) including residential schools. and the “Sixties Scoop.” Residential schools were boarding schools for Indigenous children between the ages of 5 and 16 years old that operated throughout Canada. The earliest residential schools predated Confederation and were run by church missionaries. The Government of Canada began to play a role in the development and administration of this system as early as 1874 as part of its federal responsibility under the Indian Act. An amendment to the Indian Act in 1920 made it mandatory for every status Indian child to go to residential school. By the 1930s, the federal government was aware that the residential school system was failing to meet its goals. In 1936, R.A. Hoey, superintendent of welfare and training for Indian Affairs, conducted an internal assessment that revealed significant financial and operational inefficiencies (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada, 2015b). Despite his recommendation for shifting toward day schools, the churches involved in operating the schools, including the United Church, Anglican Church, and Catholic Church, resisted such changes and pushed for further assimilation efforts (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada, 2015b).

By the 1940s, Indian Affairs officials became more openly committed to closing the residential school system, not only because it failed to meet its goals but also because it represented an ongoing financial burden. Residential schools were consistently underfunded, with much of the Indian Affairs budget strained to keep the system operational (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada, 2015b). Although the federal government increased funding periodically, it was never sufficient to address the chronic issues plaguing the schools, including deteriorating facilities, inadequate nutrition, poor staffing, and neglect. As a result, the government saw the closure of residential schools as a means to cut costs, especially as the system was no longer seen as necessary for the majority of Indigenous children (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada, 2015b) . In 1969, when the federal government took full administrative control of the remaining residential schools, the decision was not driven by a deliberate policy shift, but rather by a federal labor board ruling that required the government to assume full responsibility for its own actions (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada, 2015b).

Despite the government’s efforts to reduce costs, residential schools remained operational into the 1960s due to a lack of classrooms in day schools, which left Indigenous families with limited options (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada, 2015b). Ongoing struggles between the churches that wished to continue residential schooling for religious conversion, and the government which wishes to reduce costs, led to further underfunding and neglect. Even as residential school enrolment began to decline in favour of day schools, many children continued to suffer the consequences. Separated from their parents, they were poorly housed, poorly fed, and poorly educated, while also being subjected to harsh discipline, emotional neglect, and, in many cases, physical and sexual abuse due to inadequate oversight and supervision (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada, 2015b). By the 1980s, only sixteen residences remained in operation, and the last residential school closed in 1996. It is estimated that 150,000 children were forced to attend these schools between 1876-1996 (Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada, 2015a).

The primary objective of the residential schools was to educate and train all Indians in the norms of Canadian society. The schools were designed to provide a religious education that would foster European values, while teaching fundamentals about farming and other related industrial trades. Indigenous languages and customs were suppressed in order to aid the processes of assimilation. Indigenous children are the only children in Canadian history who have been statutorily designated to attend residential educational institutions apart from their families and communities because of their race. Many children never returned home, as mortality rates of children at these schools was extremely high (see Figure 3-1). In some Indigenous communities, this institutionalization continued for decades, and its many intergenerational effects continue to wreak havoc in Indigenous communities.

Figure 3-1: A comparison of mortality rates for students in residential schools and Canadians serving in WWII. Source: http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/truth-and-reconciliation-commission-by-the-numbers-1.3096185 Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

Watch the documentary video Canada’s Dark Secret from Al Jazeera English.

Next, comment on the whiteboard with the story or aspect of the video you found most striking.

Even with the 1950s policy shift away from residential schools to day schools, governmental policies of intervention and assimilation along family and kinship lines were not extinguished; they merely continued in a different format. One such policy program is now widely known as the “Sixties Scoop.” This policy practice was predicated on a set of western-based norms and family values that favoured the two-generation nuclear family household participating in an advanced capitalist society of wage earners and consumers. State institutions and activities were then used to determine what kind of people Indians should be and what kind of conditions they should exist in (Wotherspoon and Satzewich 2000, 83), which eventually served to justify the widespread removal of children from Indigenous homes and adopting them into non-Indigenous homes without regard for unique Indigenous cultural values or standards.

The residential school policy and the “Sixties Scoop” had significant negative impacts on Indigenous family and community life. Indigenous children were routinely separated from their families and their communities, prevented from speaking indigenous languages and from learning about their heritage and culture in a positive and culturally sensitive manner. This has resulted in intergenerational legacy that has perpetuated negative socio-economic effects for many indigenous families and communities.

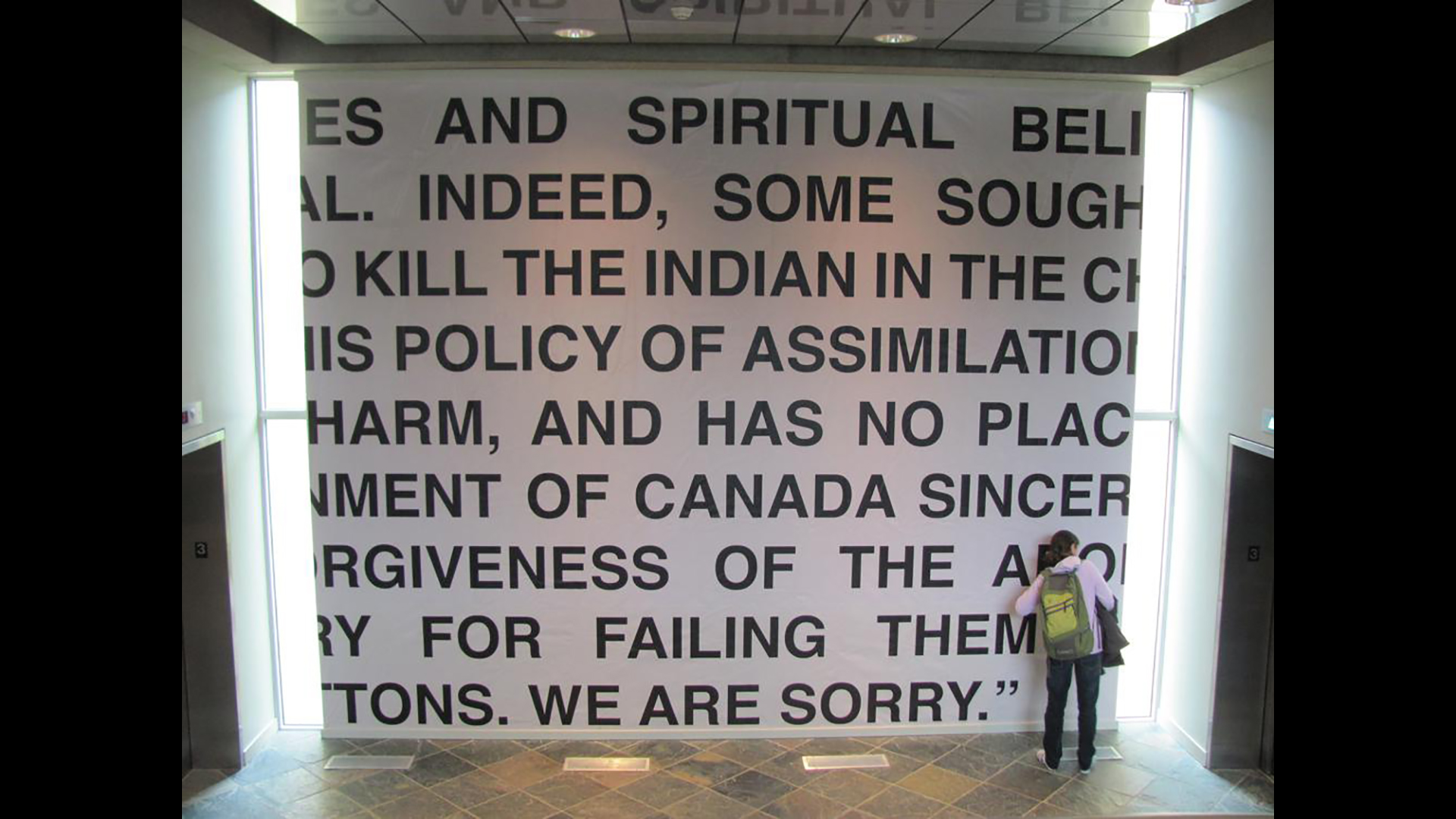

Residential Schools were problematic, not only due to their colonial nature but also due to mistreatment of indigenous children in these institutions. In 2005, the Canadian federal government announced that it would provide the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) compensation package to those affected by the residential school legacy. The IRSSA was a response to the sizable charges of physical, sexual, and psychological abuse and neglect experienced by wards of residential schools. The IRSSA resulted in two types of compensation: general compensation for all persons who attended a residential school (Common Experience Payment) as well as additional compensation under the Independent Assessment Process for residential school attendees who suffered from sexual or physical abuse and other traumatic experiences. Under the IRSSA, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was formed to document the experiences of residential school survivors.

The TRC was launched in June 2008, accompanied by a formal apology by the Government of Canada to former students of the Residential School System and an acknowledgement of the negative effects this system had on communities. The TRC documented over 3,200 confirmed deaths of residential school students through its ‘Missing Children and Unmarked Burials Project’ (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015c). However, the actual number of deaths is likely higher, but remains unclear, as the research revealed significant gaps in record-keeping. For nearly one-third of these deaths, neither the name nor the cause of death was recorded, and for nearly one-quarter, the gender of the student was missing (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015c). Aboriginal children in residential schools died at a much higher rate than other children in the general population, and for most of the schools’ history, the bodies of students who died were not sent back to their home communities (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015c). This poor record keeping was consistent with the overall neglect common to these schools.

Efforts to discover the total number of deaths continue. As of 2021, the current register of confirmed deaths by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation lists 4,118 children, but that figure reflects only a fraction of the records examined (Deer, 2021). Raymond Frogner, the head of archives at the centre, estimates that the true number of deaths may increase five-fold as the centre continues to process over four million records and 7,000 witness statements (Deer, 2021). Many burial sites remain unmarked and undocumented, with fragmented records spread across various organizations and institutions. The Commission noted that many of the cemeteries where these children were buried are now abandoned, disused, and vulnerable to disturbance.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission also noted a shocking number of testimonials that detailed child abuse. In this process, the Commission discovered that mistreatments in residential schools were not isolated incidents but widespread practice in many institutions. The TRC issued its final report in 2015. This report contained 94 Calls to Action. The TRC targeted areas of residential school legacy (child welfare, education, language/culture, health, and justice) as well as recommendations for future reconciliation between Indigenous peoples and all levels of government.

Consider the use of the term “cultural genocide” as applied to the Residential School Systems. Refer to the definition of “cultural genocide” in this short article.

Do you believe the Residential School Systems should be classified as a form of cultural genocide?

Complete the class poll below.

[poll response link]You can see the results below.

[live results link]Canada’s history of colonial and assimilationist polices has had detrimental effects on the many aspects of Indigenous life—political, economic, social, cultural, spiritual. However, the history of colonialism has also shaped, influenced, and privileged the lives of non-Indigenous persons. Consider the ways that colonialism has shaped the education of non-Indigenous Canadians: many non-Indigenous persons did not learn about the historical injustices faced by Indigenous groups in formal education and often school curriculum focused on foundational myths about Canada that include ideas such as “Two Founding Nations”, which ignores the important role that Indigenous communities played in the successful establishment of colonial life in Canada and undermines the importance of Treaty Relationships (to be discussed in Module 4). As education occurs in many spaces outside of formal school, racist and neo-colonial attitudes continue to shape the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Cognitive imperialism has not only affected Indigenous peoples historically, but has also shaped the development of non-Indigenous ways of thinking and knowing. This has resulted in ongoing legacies of colonialism, racism, and bigotry.

Cognitive imperialism can also apply to how Indigenous peoples, culture, and practices are viewed and understood by non-Indigenous society as well. This is not simply a theoretical problem, but has tangible consequences. Consider the article Escalating racism toward Indigenous people ‘a real problem’ in Thunder Bay: grand chief from the National Post.

In what ways does cognitive imperialism manifest in Canadian communities today, and how does it impact relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians? Note your thoughts in the text box below. You may consider these reflections for your learning journal. Be sure to save and download your answer.

Overall, the full range of colonial oppression has contributed to the intergenerational loss of culture and identity in Indigenous communities. Bonita Lawrence explains the cumulative picture of profound loss that colonial policies have created in the lives of people who lived them as “loss of identity, loss of familial connections, loss of access to parents or children, loss of any sense of rootedness in community, and more profoundly, loss of language and culture” (Lawrence 2000, 75). These losses have contributed to mass social upheavals and distress apparent in high suicide rates, substance abuse, and troubling health statistics (Brockman 1997).

The invisibility of the harmful effects of colonialism on Indigenous peoples is one of its most troubling and insidious aspects (Dua, Razack and Nyasha 2005). Alan Cairns notes that the majority society did not in the past and does not now see itself as an empire ruling over subject peoples, resulting in a discrepancy in perspective that complicates our analysis of where we have come from, where we are, and how we might move forward (Cairns 2000). As a result, colonialism remains experiential and subjective. Those that have experienced colonial oppression believe in its existence and relevance unequivocally. Those that have not directly experienced the negative effects of colonialism often continue to deny its existence and relevance. For reconciliation to occur in Canada, all Canadians will need to better understand the ongoing effects of colonialism on Indigenous peoples that stem from direct government policies of the past and present.

Self Test and Answers

Quiz yourself by writing down responses to each of these questions below. When finished, click each question to reveal the suggested answer. Doing the Self-Test in this way will help you prepare for the Midterms and Final Exam.

Colonialism has led to the loss of geographic territories for Indigenous peoples, the destruction of cultural structures, imposition of external control over Indigenous political life, the creation of economic dependence of Indigenous groups on the federal government, the (re)production of racism between Indigenous and non-Indigenous citizens, and the fostering of an ideology that privileges Westernized ways of life and devalues Indigenous ways of life.

Colonialism was broadly defined as the policy by which a nation seeks to extend its control and authority over foreign territories. For this module, it refers to the practices of foreign nations (including Britain and France) assuming territorial control over Indigenous lands, as well as historical and modern Canadian government policies that sought to assimilate Indigenous populations into the mainstream Canadian socio-political environment. Colonialism in Canada is generally understood to have negative effects and consequences on Indigenous populations.

Colonialism in its various contexts has institutionally and normatively created a hierarchy where Westernized knowledge(s), practices, and institutions were seen as superior to Indigenous systems. This led to the devaluation of Indigenous ways of life, and negatively affected the ways Indigenous identity was conceptualized. The devaluation of Indigenous culture led to negative self-identification with traditional ways of life, causing a variety of political, economic and spiritual strife for many Indigenous persons.

The TRC is a component of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement with a mandate to inform all Canadians about what happened in Indian Residential Schools. The TRC documented testimonials and collected historical records on policies and operations of the schools. This project issued its final report in 2015 and was intended to facilitate reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians through education, awareness, and increased understanding of the negative effects of residential schools.

Glossary

Assimilation: a general term to describe members of one group becoming (either voluntarily or forcefully) alike a dominant societal group. This can occur through many mechanisms—social, political, cultural, economic, and spiritual.

Classical Colonialism: refers to the various policies and practices of the last four hundred years by which the primary colonizing nations of Spain, England, France, Portugal and Holland asserted a western hegemony and superiority over the New World primarily for economic profit and religious motivations.

Colonialism: is the policy by which a nation seeks to extend its control and authority over foreign territories.

Cognitive Imperialism: is the conscious and unconscious ways that Indigenous ways of life and knowledge(s) are often believed to be inferior to Westernized practices.

Neo-Colonialism: refers to recent formulations and functions of political and economic globalization that have continued the exclusion and marginalization of indigenous peoples and their participation from sites of power and decision-making.

Reconciliation: Broadly meaning a return to good relations or relationship, reconciliation in Canada refers to mending relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. The mechanisms for achieving this goal differ between groups or organizations, but the term is most often associated with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) founded to address injustices from the Residential School System.

Sixties Scoop: the widespread removal of children from Indigenous homes and adopting them into non-Indigenous homes as an assimilationist practice in the 1960s.

Totalization: a term coined by Kulchyski (2005) to define state policy experienced by Indigenous peoples. It is characterized by many scholars as ‘assimilation,’ which has worked to absorb them into the established order in all aspects of their lives.

References

Anderson, Kim and Bonita Lawrence. Strong Women Stories: Native Vision and Community Survival. Toronto: Sumach Press, 2003.

Barlett, Richard. The Indian Act of Canada. 2nd ed. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan Native Law Centre, 1988.

Battiste, Marie (ed). Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2000.

Brockman, Aggie. “When All Peoples Have the Same Story, Hu- mans will Cease to Exist”: Protecting and Conserving Traditional Knowledge: A Report for the Biodiversity Convention Office. Dene Cultural Institute, September 1997.

Cairns, Alan. Citizens Plus. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000.

Champagne, Duane. “A Multidimensional Theory of Colonialism: The Native North American Experience.” Journal of American Studies of Turkey 3 (1996): 3-14.

Deer, Ka’nhehsí:io. "Why It's Difficult to Put a Number on How Many Children Died at Residential Schools." CBC News, September 29, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/residential-school-children-deaths-numbers-1.6182456.

Dominion of Canada. Sessional Papers vol 8. First Session Of the Sixth Parliament. McLean, Rogers & Co., Parliamentary Printing, 1887.

Dickson-Gilmore, Jane. “Escaping Interventionism: Negotiating Regulation and Self-Governance in the Wake of the Indian Act.” In Law, Regulation, and Governance, ed. Michael MacNeil, Neil Sargent and Peter Swan. UK and Canada: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Dua, Enakshi, Narda Razack, and Jody Nyasha Warner. "Race, racism, and empire: Reflections on Canada." Social Justice 32, no. 4 (102) (2005): 1-10.

Giokas, John and Paul Chartrand. “Who are the Métis in Section 35?” Who Are Canada’s Indigenous Peoples? Saskatoon: Purich Publishing, 2002.

Hunter, Anna. “The Politics of Indigenous Self-Government.” In Canadian Politics: Critical Reflections, ed. Joan Grace and Byron Sheldrick. Don Mills: Pearson Education Canada, Inc., forthcoming.

Kulchyski, Peter. Like the Sound of a Drum: Indigenous Cultural Politics in Denendeh and Nunavut. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2005.

Laenui, Poka. “Processes of Decolonization.” In Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision, ed. Marie Battiste. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2000: 150-160.

Laroque, Emma. “The Colonization of a Native Woman Scholar.” In Women of the First Nations: Power, Wisdom and Strength, ed. Christine Millar and Patricia Chuchryk, with Maria Smallface Marule, Brenda Manyfingers, and Cheryl Deering. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1997.

Lawrence, Bonita. “Mixed-Race Urban Native People: Surviving a Legacy of Policies of Genocide.” In R.F. Laliberte et al. (eds.) Expressions in Canadian Native Studies. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan Extension Press, 2000.

Miller, J.R. Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Indian-White Relations in Canada. Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. “Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 2 1939 to 2000” In The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Volume 1. Winnipeg: TRC of Canada, 2015b.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. “Canada’s Residential Schools: Missing Children and Unmarked Burials” In The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Volume 4. Winnipeg: TRC of Canada, 2015c.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Winnipeg: TRC of Canada, 2015a. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Williams, Robert (Jr). The American Indian in Western Legal Thought: The Discourses of Conquest. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Wotherspoon, Terry and Vic Satzewich. First Nations: Race, Class, and Gender Relations. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 2000.

Recommended Readings

Adams, Howard. Tortured People: The Politics of Colonization. Revised Edition. Penticton: Theytus Books, 1999.

Assembly of First Nations. Plain Talk 6: Residential Schools. (n.d.). https://education.afn.ca/afntoolkit/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Plaintalk-6-Residential-Schools.pdf

Government of Canada, Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Ottawa, 1982. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-12.html

Hunter, Anna. “The Politics of Indigenous Self-Government.” In Canadian Politics: Critical Reflections, ed. Joan Grace and Byron Sheldrick. Don Mills: Pearson Education Canada, Inc., forthcoming.

Laenui, Poka. “Processes of Decolonization.” In Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision, ed. Marie Battiste. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2000: 150-160.

Warry, Wayne. Unfinished Dreams. Reprinted edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000.