Developed by Anna Hunter. Revised by Nicole Wegner, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan.

Overview

Indigenous self-governance is a topic with many considerations. Self-government stems from a desire for self-determination. For many groups, self-government inherently contains the recognition that Indigenous peoples have a right to sovereignty (expressed in many different ways). This module will discuss the concept of self-government, explore historical forms of Indigenous governance and relate them to modern desires for self-determination, as well as explain different models that Indigenous self-government can take.

- Explain the concept of self-government.

- Explain the importance of historical forms of government on modern aspirations of self-government.

- Compare different conceptions and visions of self-government through models of self-government.

- Read the module Learning Material.

- Read the Required Readings.

- Complete the optional Learning Activities. These will not be graded but will enhance your understanding of the course material.

- Complete the Self-Test and check your answers with those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Complete a Reflective Learning Journal Entry for this module within Canvas. This is a graded component.

- Check the syllabus for any other formal evaluations due.

- Territorial Visions of Government

- Communal Visions of Government

- Self-Determination

- Self-Government

- Models for Self-Governance

- Government of Canada, Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Vol. 2 (part 1, chapter 3): Governance. Ottawa: Canada Communication Group, 1996. PDF archived at https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/handle/1974/6874/RRCAP2_combined.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y [Online, read pages 232-295]

- Abele, Frances, and Michael J. Prince. “Four pathways to Aboriginal self-government in Canada.” American Review of Canadian Studies 36, no. 4 (2006): 568-595. [PDF in Canvas]

- Dacks, Gurston. “Implementing first nations self-government in Yukon: Lessons for Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique 37, no. 3 (2004): 671-694. [PDF in Canvas]

Learning Material

Indigenous peoples across Canada feature a wide array of languages, cultures and traditions. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) describes the incredible diversity of these differences in the following passage:

RCAP further explains that this diversity in experience is reflected in Indigenous peoples’ visions of government. It should not be surprising that different Indigenous people (both individually and collectively) have different visions and aspirations of the most ideal governance system. For example, some traditionalists advocate a return to the hereditary chief and clan system, while some members in the same community feel the Indian Act band council and electoral system is working fine and should be maintained.

It is important to note that despite these differences, Indigenous visions of government tend to have a common core. The Commission summarized these visions into two general goals: territorial and communal (RCAP 1996 vol. 2 “Governance,” part A, 42)

- Territorial visions involve greater authority over a traditional territory and its inhabitants, whether this territory is exclusive to a particular Indigenous people or shared with others.

- Communal visionsinvolve greater control over matters that affect the particular Indigenous nation in question: its culture, identity and collective well-being.

According to RCAP, these two general goals are complementary rather than contradictory. Many Indigenous nations seek both goals concurrently. For example, BC First Nations and the provincial government negotiate Education Delegation Agreements that ensure that schools within the particular traditional territory include appropriate cultural and language instruction for all students.

Jim Miller (2004) explains that European newcomers did not recognize the Indigenous societies they met from the sixteenth century onward as coherent, self-governing communities. He also explains that there should be no doubt that Indigenous self-government existed at contact. There were various systems of Indigenous government in place at the time of contact.

One example is the Mi’kmaq who occupied an extensive territory with a system of government that looked closely like federalism. Their population was distributed over much of the Maritimes, living in communities that could range in size from fifty to several hundred. The communities were organized into seven districts, each with its own name and governing council. In addition to community leaderships and district councils, the Mi’kmaq also claim a grand council that could mediate interests between districts and handled issues for all regions. The extended Mi’kmaq government was also part of the Wabaknaki Confederancy, an alliance organization intended for self-defence against other indigenous groupings. (Miller 2004, 56)

Across First Nations, there were similarities in governance customs, most notably the use of consensus in decision-making. An example from the Iroquois Confederacy was the informal rule that decisions had to be unanimous. (Miller 2004, 59). This practice meant that lengthy consultations were often required to reach decisions that all nations within this alliance felt were acceptable.

Another unique custom shared across various Indigenous groups was the role that women played politically in society. For instance, the Iroquois peoples were matrilineal (meaning that kinship was traced through the mother’s family). These communities had female councillors that would be responsible for selecting a new chief, or consulting in decisions on war or peace (Miller 2004, 57).

In Northwest coastal communities, the Potlatch is noted for regulating social relationships in communities. A Potlatch was a celebration in which social hierarchy or ranking was practiced through gift giving (or occasionally the destruction of property) to those in attendance. In addition to being a ceremony in which the community observed rites of passage or social shuffling, Potlatching was also a mechanism for wealth re-distribution. This practice was a unique form of community and economic regulation before it was banned under the Indian Act in 1884.

Despite nuances in organization or regional/cultural differences in governing practices, it is evident that Indigenous societies had their own mechanisms for community governance and inter-national conflict resolution prior to European contact.

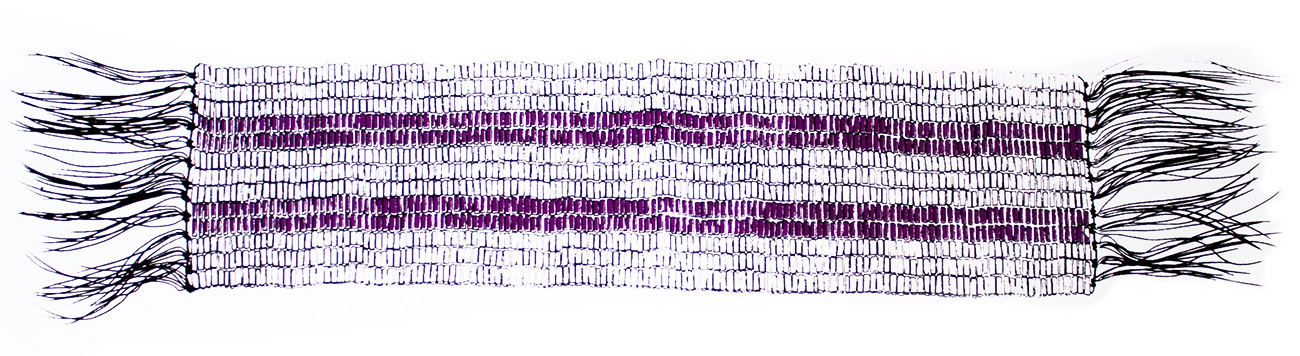

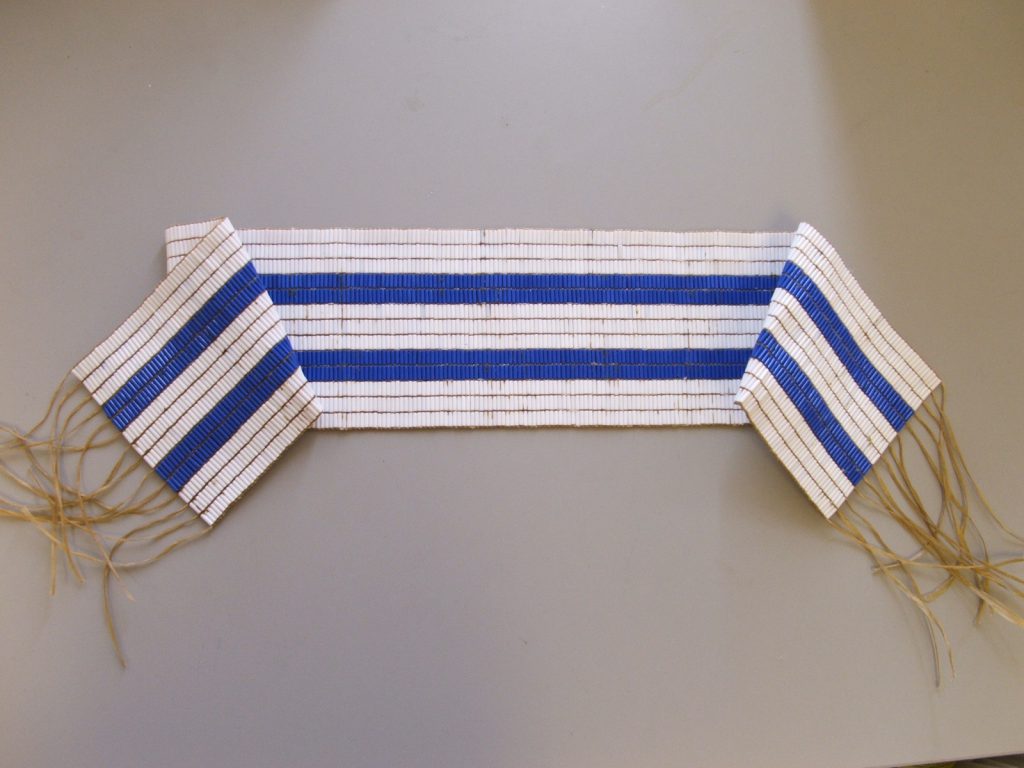

Consider the video Hodinohso:ni Governance & the Great Law of Peace – Conversations in Cultural Fluency #4, about the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy and governance practices used, as represented in various beadwork belts including the Circle Wampum, the Tree of Peace belt, and the Bundle of Arrows story. These histories show the complex systems of governance used by some Indigenous societies pre-contact.

As discussed in Modules 2 and 5, historical Indigenous governance structures were replaced by the Indian Act system and other colonial government structures (for non-Status, Metis, and Inuit Nations) in the contact and post-Confederation periods. The loss of recognized independence and autonomy has had negative effects for many Indigenous communities who desire to have greater control over the political, economic, and social well-being of their Nations.

In its most basic sense, Indigenous self-government expresses the desire of Indigenous peoples to control their own destiny, their desire for self-reliance and for the accountability of their leadership to their own people and not to the federal, provincial or territorial governments. More specifically, it is the right of Indigenous peoples to be recognized as autonomous political communities with the authority and resources to decide the course of their individual and collective futures (Murphy 2001,109). Indigenous self-governance is rooted in the desire of Indigenous peoples to secure their distinct cultures and identities for future generations. To that end, Indigenous self-governance is about negotiating tailored relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in a manner that derives a mutually beneficial set of authoritative powers between the various levels of governments. These relationships should strive to sustain the broad range of features of distinct Indigenous cultures and identities, including their histories, languages, socio-political values and ideologies, and legal systems.

Advocates assert that Indigenous self-government is an inherent right that originates in the original occupation and use of the land prior to European contact. Accordingly, it is argued that Indigenous self-government cannot be delegated or unilaterally extinguished because its source lies within the Indigenous peoples rather than from external sources such as international law, the common law or the Constitution (RCAP 1996 vol. 2 “Governance,” part A, 7). The United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) Article 3 states that “Indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development” (United Nations) However, Indigenous self-government is about choice. It cannot be imposed on Indigenous communities that are not ready or willing to undertake it. Nor can self-government be handed down in a template fashion. Self-government agreements require negotiations between the Indigenous government and the federal and provincial governments in a manner that respects the distinct cultural norms and practices of the particular Indigenous people in order to maximize its probability of success (Cornell and Kalt 1998).

In short, Indigenous cultures were diverse and varied prior to European contact. Self-governance must respect this diversity through recognition that Indigenous groups are not homogenous, and therefore cannot be given identical self-governing structures. Self-governance is not only about respecting the inherent right of this practice for Indigenous groups, but also about respecting the diversity and variation in forms that is required for success.

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples notes that: “The exercise of self-determination and self-government will assume many different forms according to Aboriginal peoples differing aspirations, circumstances and capacity for change.” (RCAP 1996 vol. 2, “Governance,” part A, 164). In order to conceptualize the term Indigenous self-government in the face of multiple and diverse visions of Indigenous governance, it is useful to consider the various forms of self-government as expressed through theoretical models for self-governance (see Figure 8-1). The models contain varying degrees of sovereignty and authority. As these are ‘models’ it is important to remember that future development of Indigenous self-governance systems must not necessarily adhere to the specific parameters of these models, but could draw upon favourable aspects of any model to create a system that works best for their community or nation. The distinction in these models largely rests upon how autonomous the governance system is and what degree of authority and responsibility the governance system will manage.

Figure 8-1: Models of Indigenous Self-Governance. Permission: Courtesy of course author Nicole Wegner, Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan.

Indigenous Self-Regulation

Indigenous self-regulation refers to the negotiated acceptance of delegated, municipal-style authority and its corresponding dependency upon higher levels of government for funding and authority. In the Canadian context, this municipal style of Indian government is strictly limited to Indian reserve land, which is perceived as problematic on two accounts.

First, it excludes Indigenous groups that do not hold a reserve land base like the Métis and non-status Indians. Second, as Patricia Monture-Angus explains, this perspective is unsatisfactory from a traditional understanding because it is mired in the colonial institution of reserve land, and does not reflect Indigenous understandings of their relationship with the territory (Monture-Angus 2002, 30). However, the municipal form of delegated authority does offer the benefit of granting Indigenous governments the power to pass laws on a range of matters in a rather uncomplicated and expedient manner. These powers may include the administration and management of band lands (including access to and residence on reserved lands), education, social welfare and health services, and the local taxation of reserve lands.

See the article The Sechelt Indian Band: An Analysis of a New Form of Native Self Government (Carol E. Etkin). This article focuses on the Sechelt First Nation self-government agreement, which shares characteristics with the Indigenous self-regulation model discussed above. Answer the following mini-quiz:

Constitutional Self-Government

Constitutional self-government involves the negotiated control and authority over specific spheres of jurisdiction or authority in accordance with section 35 of the Constitution. Constitutional self-government focuses on a limited range of cultural and territorial interests through a core-periphery distinction (Macklem 2002,167; RCAP 1996 vol. 1, “Governance,” part A, 126). Those elements of Indigenous culture and territorial interests that fall within the core of the Indigenous distinct identity are negotiable, and those that fall outside to the periphery are non-negotiable. In this situation, constitutional Indigenous self-government includes the capacity to assume jurisdiction over the education, health and welfare of community members within their traditional territory. Constitutional Indigenous self-government also includes the authority to make economic and social policy, administer taxes, pass laws, manage land and natural resources and negotiate with other governments. The scope of constitutional Indigenous self-government does not include areas that have a major impact on adjacent jurisdictions or areas that are otherwise the object of transcendent federal or provincial concern (RCAP 1996 vol. 1, “Governance,” part A, 126).

Consider the following article on the Nisga’a First Nation Self-Governance Agreement and answer the following mini-quiz:

Indigenous Self-Determination

Another theoretical model is Indigenous self-determination. Self-determination encompasses the internationally recognized right to a broad range of cultural, economic, legal, political and jurisdictional content (Green 2003,8). The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides the following explanation: “Indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.” From this broad definition, S. James Anaya identifies two normative strains of substantive self-determination:

First, in what may be called its constitutive aspect, self-determination requires that the governing institutional order be substantially the creation of processes guided by the will of the people, or peoples, governed. Second, in what may be called its ongoing aspect, self-determination requires that the governing institutional order, independently of the processes leading to its creation or alteration, be one under which people may live and develop freely on a continual basis (Anaya 2000,81).

Self-determination does not per se entail a right to secede from existing states, nor does it imply an interest in the right to secede. E.I. Daes notes that: “most indigenous peoples acknowledge the benefits of a continued partnership with existing states in view of their small size, limited resources and vulnerability” (cited in Grand Council of Crees 1995,56).

Examine the Infographic on Yukon’s history of land claims and self-government, and consider the Yukon Umbrella Agreement and the self-government negotiations that have occurred concurrently.

Based upon the jurisdictional divide (also discussed in our reading by Dacks), do you think that the Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA) reflects characteristics of the Indigenous Self-Determination model?

Complete the class poll below by voting “yes” or “no”.

You can see the results below.

Expand upon your choice by adding an elaborating statement underneath one of the columns in the whiteboard below.

Tribal Sovereignty

The next theoretical model is Tribal Sovereignty, which is used by some Indigenous peoples in reference to the fact that they have never ceded their nationhood, independence, or their inherent right to self-government and self-determination. David Wilkins (2007) provides the following definition of tribal sovereignty in the American tribal context:

In the Canadian experience, “tribal sovereignty” is grounded in the ideal of independence and freedom with the right to a territory of its own. Accordingly, tribal sovereignty advocates argue that it is solely up to the Indigenous group to determine and legitimate non-negotiable parameters of government powers and jurisdiction.

Consider the video How To Stop An Oil And Gas Pipeline: The Unist’ot’en Camp Resistance from AJ+ Docs, which centers on the Unist’ot’en clan protection/protest camp.

Do you think that this constitutes a form of Tribal Sovereignty? Which elements of this organization reflect the theoretical components of the Tribal Sovereignty model?

Vote for which elements you think are represented by selecting them in the following poll (you can select multiple items).

You can see the results below.

Secessionist Independence

The final model of self-governance is largely theoretical. It involves secessionist self-determination with corresponding claims of accession to political and territorial independence. In the Canadian political context, the right to secede is exceedingly rarely asserted by Indigenous peoples. Even during the 1995 Québec Sovereignty referendum, the affected Indigenous groups took a position that invoked principles of self-determination, not secession (Grand Council of the Crees, 1996).

Generally, every example of Indigenous self-government corresponds to elements in the models of Indigenous government. In Canada, there are First Nations that have accepted limited forms of government in their communities, First Nations that have negotiated more comprehensive agreements, and First Nations that continue to politically position themselves to accept only complete control and sovereignty. The 1986 Sechelt Indian Band Self-Government Act reached by the Sechelt First Nation of British Columbia offers an excellent example of the self-regulation model because of its delegated, municipal-style form of Indigenous self-government. In this case, Sechelt Indian Band members voted in a referendum on March 15, 1986, to approve the transfer by Her Majesty in right of Canada to the Sechelt Indian Band of titles in all Sechelt reserve lands, recognizing that the Sechelt Indian Band would assume complete responsibility, in accordance with this Act, for the management, administration and control of all Sechelt lands. The Act granted authority to the Sechelt Band to exercise delegated powers and negotiate agreements about specific issues. It also granted the elected council the power to pass laws on a range of matters that include access to and residence on Sechelt lands, administration and management of lands belonging to the band, education, social welfare and health services, and local taxation of reserve lands. Finally, the agreement grants municipal status under provincial legislation to the Sechelt Indian band.

Considering another self-government model, we can look at the 1998 Nisga’a Final Agreement ratified by the Nisga’a Nation, the federal government and the Province of British Columbia. According to section 23 of the Nisga’a Final Agreement, this comprehensive agreement “exhaustively sets out Nisga’a section 35 rights, the geographical extent of those rights, and the limitations to those rights, to which the Parties have agreed.” This Agreement provides for representative and democratic systems of government for the Nisga’a Nation, and permits primary responsibility to the Nisga’a Lisims Government in a number of central areas including: citizenship, culture and language, regulation of trade and commerce, child and family services and education. Nisga’a laws dealing with child and family services and education are subject to comparison and harmonization with provincial standards. In other areas like fish and wildlife resource management, the Nisga’a Lisims Government will share concurrent law-making authority with provincial and federal counterparts.

The Six Nations or Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse) Confederacy offer an excellent example of tribal sovereignty based on their longstanding assertion of independence and sovereignty within the international setting. For over three centuries, the Confederacy has steadfastly abided to their intergovernmental understanding of co-existence based on autonomous and distinct jurisdictions (Johnson 1986,11). This understanding is symbolized through the Gus-Wen-Qah, or the Two Row Wampum belt (see Figure 8-2). Darlene Johnson explains the principles of the Two Row wampum belt in the following passage:

The ideology of autonomy symbolized in the Two-Row Wampum has met serious challenges through colonial incursions, yet it continues to motivate the constituent groups of the Haudensaunee to various degrees. In Heeding the Voices of our Ancestors, Gerald Alfred states that the Mohawk of Kahnawake consider progress as movement towards the ideal of complete autonomy through a process of divesting themselves from colonized status and regaining the status of an independent sovereign nation (Alfred 1995,102).

The applicability of the models of self-government to the diverse range of self-government options should now be clear. Besides providing a conceptual tool, the models of self-government also capture the reality that Indigenous self-government is more than an unrealized dream for the future – it is already operating through a variety of different functional arrangements throughout the country. Interestingly, each example of self-government also tends to build on each other in order to increase its overall potential and viability. As Wayne Warry explains: “self-government is an emergent, iterative process – its meaning and validity become clearer with its practice.” (Warry 2000,49). The prevalence of self-government models already in operation should serve to recognize the many benefits of the policy approach of Indigenous self-government. However, vigilance must still be afforded to its form and content to ensure that Indigenous peoples are provided the appropriate level of authority and resources necessary to direct the government processes that affect their communities.

Self Test and Answers

In its most basic sense, Indigenous self-government expresses the desire of Indigenous peoples to control their own destiny, their desire for self-reliance and for the accountability of their leadership to their own people and not to the federal, provincial or territorial governments.

As Indigenous groups had unique but varied practices of government prior to European contact, modern aspirations for Indigenous self-governance strive to represent this diversity through customized governance agreements and practices that reflect various needs of diverse First Nations groups.

There are five broad forms of governance outlines in the models of self-government: a) self-regulation, b) constitutional self-government, c) self-determination, d) tribal sovereignty, e) secessionist independence.

Glossary

Communal Visions of Government: Involve greater control over matters that affect the particular Indigenous nation in question: its culture, identity and collective well-being.

Diversity: A state of having multiple cultures, languages, or other identity markers within a larger group or society.

Iroquois Confederacy: An alliance between various conflicting Iroquois groups that anthropologists suggest was formed sometime between 1400-1600 AD. This alliance contained Mohawk, Onodaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca nations and is considered an Indigenous example of inter-national cooperation in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Potlatch: A ceremonial feast or celebration hosted by an incumbant social leader where lavish gifts were given to guests and social hierarchical practices were reinforced through customary re-tellings of social orders.

Self-Determination: The desire of Indigenous peoples to control their own destiny, their desire for self-reliance and for the accountability of their leadership to their own people and not to the federal, provincial or territorial governments.

Self-Government: Varied institutional forms of Indigenous groups assuming political, economic, or social control over their populations.

Territorial Visions of Government: Involve greater authority over a traditional territory and its inhabitants, whether this territory is exclusive to a particular Indigenous people or shared with others.

References

Alfred, Gerald R. "Heeding the voices of our ancestors: Kahnawake Mohawk politics and the rise of native nationalism in Canada." (1995): 2121-2121.

Anaya, S. James. Indigenous peoples in international law. Oxford University Press, USA, 2004.

Cornell, Stephen, and Joseph P. Kalt. "Sovereignty and nation-building: The development challenge in Indian country today." American Indian Culture and Research Journal 22, no. 3 (1999): 187-214.

Government of Canada, Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. “Governance.” Report of the Royal Commission on Indigenous Peoples vol. 2 (part 1, chapter 3). Canada Communication Group: Ottawa, 1996.

Grand Council of the Crees (of Quebec). "Sovereign Injustice: Forcible-Inclusion of the James Bay Crees and Cree Territory into a Sovereign Quebec." Nemaska, PQ: Grand Council of the Crees (1995).

Green, Joyce. "Self-determination, citizenship, and federalism: indigenous and Canadian palimpsest." In Michael Murphy (Ed.), Canada: The State of the Federation 2003. Reconfiguring Indigenous-State Relations (pp. 329-351). McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003.

Hunter, Anna. “The Politics of Indigenous Self-Government.” In Joan Grace and Byron Sheldrick (Eds.), Canadian Politics: Critical Reflections. Don Mills: Pearson Education Canada, Inc., 2006.

Johnson, Darlene. “The Quest of the Six Nations Confederacy for Self-Determination.” University of Toronto Faculty of Law Review, 44, no. 1, 1-32 (1986, Spring).

Macklem, Patrick. Indigenous Difference and the Constitution of Canada Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

Monture-Angus, Patricia. Journeying Forward: dreaming First Nations independence. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. (second printing), 2002.

Murphy, Michael. “Culture and the Courts: A New Direction in Canadian Jurisprudence on Indigenous Rights?“ Canadian Journal of Political Science, 34,

no. 1, 109-129 (2001).

Smith, Melvin. “Some Perspectives on the Origin and Meaning of Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.” Public Policy Sources, no. 41. Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2000. Available online at:

http:// www.fraserinstitute.ca/shared/readmore.asp?sNav=pb&id=200

Warry, Wayne. Unfinished Dreams. Reprinted edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000.

Wilkins, David E. American Indian Politics and the American Political System

(p. 51). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007.

United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2008. Available online at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Recommended Readings

Hoffamn, Ross and Andrew Robinson. “Nisga’a Self-Government: A New Journey Has Begun” The Canadian Journal of Native Studies. 2 (2010): 387-405.

Hunter, Anna. “The Politics of Indigenous Self-Government.” In Joan Grace and Byron Sheldrick (Eds.), Canadian Politics: Critical Reflections. Don Mills: Pearson Education Canada, Inc, 2006.

Miller, J.R. “‘According to Our Ancient Customs’: Treaties.” In Lethal Legacy: Current Native Controversies in Canada. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart (2004): 52-105.