Developed by Marcel Guay. Revised by Nicole Wegner, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan; Rebecca Major, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan and Métis Nation-Saskatchewan Area Representative.

Overview

The first part of this module addresses identity issues in Métis history. Defining the Métis People has been a long process which has fluctuated from including all so-called "mixed blood" Aboriginals to narrow definitions of the Métis as being only descendants of the Red River Colonies in the mid-1800s. This module will introduce historical and modern identity and political issues affecting Métis groups to show the unique political challenges that Métis People have endured.

The second half of the module will focus on Métis political organization in Saskatchewan. Recent reorganizations of the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan (MN-S) have been based on the Métis Act 2002 and governance structures laid out in the Act. The Métis People have had a modern Constitution since the 1980's and have organized themselves to run social and business programming with federal Canadian government funding and provincial funding. These programs have set up special housing, work, training and education programs to benefit the Métis People and have also been the source of Métis business and corporate development in the province. Larger organizations include women's groups and national lobby groups, which represent the special Aboriginal rights of the Métis People to the federal and provincial governments.

The module will conclude with a discussion of recent issues faced by the MN-S and ongoing solutions to address these governance challenges.

- Investigate the historical background of the Métis People in Canada.

- Examine developments in legal recognition of Métis status in Canada.

- Identify the existing governance structures of the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan.

- Examine the basic structure of the Métis Nation in Saskatchewan as laid out in the Métis Act and the Constitution of the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan.

- Discuss governance issues faced by the Métis Nation.

- Read the module Learning Material.

- Read the Required Readings.

- Complete the optional Learning Activities. These will not be graded but will enhance your understanding of the course material.

- Complete the Self-Test and check your answers with those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Complete a Reflective Learning Journal Entry for this module within Canvas. This is a graded component.

- Check the syllabus for any other formal evaluations due.

- Métis Nation-Saskatchewan (MN-S)

- Métis Act 2002

- R. v. Powley

- Daniels v. Canada

- Section 91 (24), Constitution Act 1867

- Gaudry, Adam. “The Métis-ization of Canada: The process of claiming Louis Riel, Métissage, and the Métis people as Canada’s mythical origin.” aboriginal policy studies 2, no. 2 (2013): 64-87. [PDF in Canvas]

- Andersen, Chris. “’I’m Métis, What’s your excuse?’: On the Optics and the Ethics of the Misrecognition of Métis in Canada.” aboriginal policy studies 1, no. 2 (2011): 161-165. [PDF in Canvas]

- Macdougall, Brenda. “The Myth of Métis Cultural Ambivalence.” Contours of a People: Metis Family, Mobility, and History 6 (2012): 422-464. [PDF in Canvas]

- Sawchuk, Joe. “Negotiating an identity: Métis political organizations, the Canadian government, and competing concepts of Aboriginality.” The American Indian Quarterly 25, no. 1 (2001): 73-92. [Library link in Canvas]

Learning Material

Métis is a term originating in the Latin “miscere” (to mix) that was used to describe children of First Nations women and French fur traders in the 18th century (Métis Nation of Alberta). Métis culture developed during the fur trade, as liaisons between European traders and Indian groups. A unique culture was cultivated, including language, trading technologies, legal and political practices and traditions. In 1763, the Royal Proclamation awarded the Crown responsibilities for Indigenous peoples and enshrined land protections. The Proclamation did not extend to Métis peoples or their political rights, as they were not recognized as a sovereign people that time. In addition to facing social stigmas, Métis peoples encountered much impoverishment despite efforts of the rebellion led by Louis Riel in the late 1800s to reclaim traditional territories and resources. It was not until the 1930s that lobby groups in Alberta, including Peter Tomkins, were able to appeal to the government for access to Métis lands.

Like First Nations, Métis People are not a homogenous group, as there are many local, regional, and cultural variations of groups who identify as Métis (Sawchuck 2001). There are, however, contentions between western “Red River” Métis groups and Métis populations in Ontario or Labrador about the definition of “Métis” in Canada and whom is eligible to use this label. The Métis Association of Alberta (now called the Métis Nation of Alberta) has offered historically evolving definitions of who can be considered Métis. Many provincial Métis organizations now have their own membership criteria which defines who is considered Métis, usually based upon criteria set by the Métis Nation Canada (MNC). However, unlike the parameters for identity set by the Indian Act for First Nations in Canada, there is no official federal governmental definition of “Métis”.

One of the most important developments in Métis rights history was the affirmation of Métis peoples as Aboriginal Peoples in section 35 of the Constitution Act 1982. The lobbying of Métis activists to have Métis People included in section 35 (2) of the Constitution Act 1982 was a significant political victory for Métis and non-Status Indian groups.

Watch the video of Jim Sinclair, MNC, and his activist attempts to have Métis Nationhood recognized by the federal government.

In 1983, the Métis National Council was formed, comprised of the Métis Nation British Columbia, Métis Nation of Alberta, Métis Nation-Saskatchewan, Manitoba Métis Federation, and Métis Nation of Ontario. The Métis National Council (MNC) and affiliates are the only recognized Métis political bodies by the federal and provincial governments in Canada. Because of this, the only recognized definition of “Métis” identity is also that provided by the MNC and this definition does not recognize all mixed-heritage Indigenous groups (for example, Labrador Métis people go by “Southern Inuit”, and have struggled to have their Aboriginality recognized by governments).

According to the Métis National Council, individuals must provide proof of their Métis status. Review Métis Nation Citizenship and the Métis Registration Guide provided. Next, select the correct statement from each of the sets in the summary-builder below to determine the criteria needed for Métis status.

The Constitutional affirmation of Métis People’s Aboriginality was a huge political accomplishment, however a consequence of this achievement resulted in a splitting of a long-standing political union between Métis and non-Status Indian groups; section 35 (2) enshrined legal rights for the Métis Nation but not for non-Status Indians (Sawchuk 2001). The post-1982 cleavage between Métis and non-Status Indians reflects a growing awareness that these two groups are not the same, as most Métis organizations note that Métis Nationhood involves a distinct cultural, historical, and linguistic heritage. This was reflected in a 1990 definition of the Métis National Council that specific Métis were “an aboriginal people distinct from Indian and Inuit” (Sawchuk 2001). As discussed in Module 6, R. v. Sparrow (1998) provided a new legal definition of how Métis could be defined according to section 35 (2), as “a person of aboriginal ancestry; who self-identified as a Métis; and who is accepted by the Métis community as a Métis”. While this recognition is important in securing Métis Nationhood under section 35 (2), it has raised some concerns about the conflation of Aboriginal and Métis identities (Anderson 2011).

Chris Anderson explains that “Métis identity carries the freight of more than a century of official Canadian attempts to impose binary ‘truths’ (‘Indian’ or ‘Canadian’) onto Indigenous social orders” (Anderson 2011, 164). He resists defining “Métis” as “mixed-race people” as it reduces identity to racialized representations and also serves to diminish the complexity of historical, political, cultural, and linguistic distinctiveness that many Métis Peoples see as underpinning their identity. This perspective affirms not only the distinctiveness of the Métis Nation as a cultural identity, but also the inherent sovereignty that Métis People hold as a distinct Indigenous nation within Canada. In short, like other notions of Aboriginality, Métis identity is complex and there is a lack of consensus among those who self-identify as Métis about the appropriate ways in which this label (and membership in political organizations) should be applied. For many, being Métis is not simply having mixed heritage, but it is about a connection to a distinct politico-cultural heritage—for some, intimately connected with Louis Riel and the Red River resistance and for others, more broadly tied to a broader set of Métis community histories and geographies.

In 2003, the identification of Métis persons and their rights was refined based on a legal precedent set through a Supreme Court of Canada case. R. v. Powley was a case based on a 1993 illegal hunting charge laid on two Ontarian Métis males. After being found in possession of a moose out of season, the accused argued that provincial hunting laws violated their Aboriginal right to hunt. R. v. Powley does not provide a universal definition of who can be considered Métis, but did provide a precedent in legal recognition of Métis section 35 rights. Like R. v. Sparrow and R. v. Van der Peet, this decision spurred discussion on who could be granted these rights, and this case provided guidelines for who can be legally recognized as Métis. To be considered a claimant of section 35 rights, an individual must demonstrate their membership in a present-day Métis community, and this community must be able to trace its existence back to an historic Métis community with a distinctive culture.

The affirmation of Métis rights under section 35 has meant that Metis People have the opportunity to seek legal recourse should their section 35 (2) rights be infringed upon. However, this recognition did not specify the government take any further actions nor that the federal government had any special obligations to Métis Peoples.

To deal with the discrepancy that existed in federal treatment of Aboriginal peoples, Harry Daniels, a Métis activist from Saskatchewan, his son Gabriel Daniels, Leah Gardener (a non-Status Indian), and Terry Joudrey (a non-Status Indian), with the assistance of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP), filed a case against the Crown (Daniels v. Canada), represented by INAC and the Attorney General of Canada. The plaintiffs sought for the Court to declare that Métis and non-status Indians should be considered “Indian” under section 91 (24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. This clause provides to Parliament the exclusive legislative authority over “Indians and lands reserved for Indians” but does not stipulate any legal obligations or actions on the government behalf. In the Daniels case, the plaintiffs also demanded that the Crown owes a fiduciary duty to them and that they have the right to be consulted by the federal government on a collective basis as status Indians had been.

While the Court agreed to the first clause, it declined the second two. In 2013, the federal government appealed the ruling at the Federal Court of Appeal. The Court upheld the original decision, although it excluded non-Status Indians from the scope of application. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) heard a second appeal and ruled in favour of the original court decision that Métis and non-Status Indians should be considered “Indian” as the term applies in section 91 (24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. The SCC found that the secondary and tertiary demands relating to a fiduciary relationship and consultation had already been established in existing precedents under Delgamuukw v British Columbia (established fiduciary relationship) and Haida Nation v British Columbia, Tsilhqot’in Nation v British Columbia, and R. v. Powley that established contexts in which the Crown has a duty to negotiate as related to Aboriginal rights.

The exact ramifications about financial obligations and federal-Métis relations have yet to be established. Consider the next Learning Activity that explores some of these issues.

Review the article 6 Things You May Want to Know About the Daniels Decision to help you answer the mini quiz below:

An interesting political consideration of the SCC ruling is that it was noted “there is no need to delineate which mixed-ancestry communities are Métis and which are non-status Indians. They are all ‘Indians’ under s. 91 (24) by virtue of the fact that they are all Aboriginal peoples” (Supreme Court of Canada 2016). The case explains that:

This stipulation is particularly interesting in relation to our required reading by Anderson about the distinctions between Métis and non-Status Indians and the challenges associated with equating Métis People with “mixed-ancestry” definitions.

Watch the video Being Métis from The Agenda with Steve Paikin.

Next, add a word to the input box below that you believe is representative of Métis self-identification, according to the testimonials in the clip.

As words are added, the word cloud below will rearrange and show the most common responses of the class.

Considering this overview of Métis political identity and history, governance practices of the Métis Nation(s) are a useful case study to explore issues in Indigenous Governance. As Métis People have been historically excluded from the Indian Act system, their path to self-governance and political management has taken a unique path. The remainder of this module will focus specifically on the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan government structures and issues faced with Métis governance in Saskatchewan.

The Métis population in Saskatchewan is made of individuals who self-identify with Métis ancestry and may or may not be members of the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan (MN-S). Estimates of the number of people vary from Statistics Canada estimates of 380,000 in Canada with estimates of 50,000 in Saskatchewan alone. The MN-S membership includes all members who have obtained Métis Citizenship cards through their local organizations which number about 40,000 and these are usually accepted as members of the MN-S. The General Assembly of the MN-S includes all of these members.

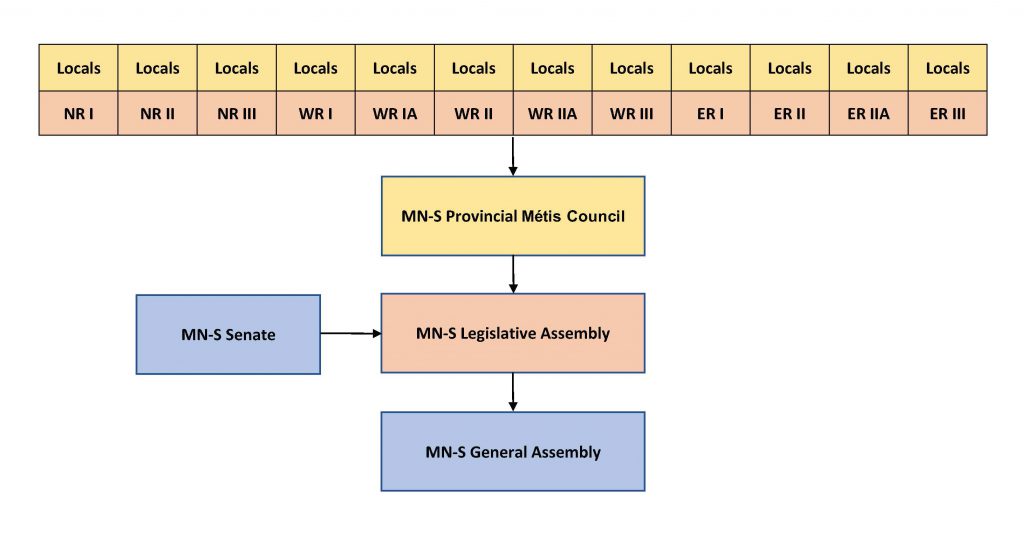

The governance structure of the MN-S is depicted in Figure 7-1. The Métis Nation Legislative Assembly (MNLA) is the governing body of the MN-S. The MNLA is an elected organization that meets and enacts laws. The MNLA is made up of the Provincial Métis Council (PMC), Women and Youth Representatives, and elected Métis Local presidents.

The Provincial Métis Council (PMC) is made of:

- 12 Regional Representatives elected within their region by all citizens

- 1 Métis Youth Representative elected in their youth organization

- 1 Métis Women’s Representative elected in the women’s organization

- Elected Executive of the MN-S (President, vice-president, treasurer and secretary), elected province-wide by all Métis citizens

The Saskatchewan Métis Act also constitutes an MN-S Secretariat Inc. body, which deals directly with the provincial government. The secretariat is the administrative body by which policies and programs of the MN-S may be carried out and administered. Métis Locals, which make up Regional Councils, operate separately and may also act as separate governing bodies for their particular territories when it comes to programs and grant acquisition.

You will see from Figure 7-1 that there are Local Representatives from various regions in the province: North Region (NR), West Region (WR), East Region (ER). These Locals comprise the Provincial Metis Council (PMC). The PMC, which includes the Youth and Women’s representatives and the elected Executive, make up the Metis Nation Legislative Assembly.

Figure 7-1: Governance Structure of the MN-S. Source: Rebecca Major, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan and Métis Nation-Saskatchewan Area Representative.

The Métis population has several affiliated bodies including the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan itself that acts as the political voice for all members and groups. MN-S is connected to the other Métis organizations. Each Métis affiliate is a separate corporation (including the MN-S which is under the Saskatchewan Non-Profit Corporations Act or the Business Corporations Act).

Affiliated Métis organizations include:

- The Clarence Campeau Development Fund, which incorporated in 1997 and reorganized in 2001 under an amendment to the Gaming Act to encourage Métis business development.

- SaskMetis Economic Development Corporation (SMEDCO), a Métis owned lending organization created to finance Métis business.

- Métis Family Community Justice Services of Saskatchewan Inc. (MFCJS)

- The Provincial Métis Housing Corporation (PMHC), which is a delivery agent for Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and the Municipal Government Housing Division.

- The Gabriel Dumont Institute (GDI), which was incorporated in 1988 to meet educational and training needs.

- The Métis Addictions Council of Saskatchewan, which is a non-profit society. (MACSI)

When considering that the Métis Nation does not receive the same type of funding arrangements as the federal government (INAC) has with First Nations, what are the advantages of having Métis-specific organizations that can assist the Nation in economic development, justice, housing, education, and health/addictions? List some of your ideas on the whiteboard below.

The Métis Act, effective January 28, 2002, provides a way for the coordination and cooperation for the MN-S and the Saskatchewan Government through a bilateral process under which important issues (land, harvesting governance, capacity building) can be addressed.

The MN-S Secretariat Inc. is the administrative body recognized under the Métis Act by which the policies and programs are carried out. The people who make up this board are the members of the provincial Métis Council of the MN-S. These members control and direct all affairs and formalize the decisions by resolution or bylaw. According to the Métis Consultation Panel (2006), there are concerns with the Métis Act, which are discussed below:

- Provincial legislation is not sufficiently detailed concerning Métis rights and the responsibilities of the MN-S.

- Many Métis are unaware of the Act’s existence and/or relevance to the MN-S.

- Those who are aware of the Act’s existence believe that there are significant gaps in the detailing of the Métis Act. This means that there are not enough details to ensure that there are sufficient checks and balances of the board members.

Potential moves toward reforms of the Métis Act include the possibilities of:

- Directing the Government of Saskatchewan legal advisors to adjust the Métis Act and the Non-Profit Corp Act to allow more details concerning Métis rights and MN-S responsibilities.

- Developing a discussion paper on the possible suggestions for amendment.

- Asking a committee of the provincial legislature to hold similar public hearings on the same issue, so Métis people can share their opinions or proposed reforms.

The Preamble of the Constitution

Within the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada Métis people are a distinct society, a cultural group different from the Indians and the Inuit. Having endured many hardships (social, political, and dispossession) since the 1800’s, Métis people have been struggling to restore their inherent rights: land base and resources, self-government, and government institutions. The Métis people have been pursuing this restoration through political, legal and constitutional recognition. As a result of these pursuits the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan (MN-S) has emerged. This body has adopted a constitution (Constitution of the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan) which outlines its objectives, mandates, and governance structure through various articles (1-16). The first asserts the right of all Métis to self-determination including to freely determine political status, and freely pursue economic, social and cultural development.

The constitution is organized into sections. In the preamble of the MN-S there are four points that the citizens of the MN-S declare, leading into 21 rights and responsibilities of the citizens. The following articles are noteworthy (Métis Electoral Consultation Panel, 2006):

- Article 1: Names the organization Métis Nation-Saskatchewan as of November 18, 2000.

- Article 2: Métis Nation Legislative Assembly. This article explains that the Métis Nation Legislative Assembly (MNLA) is the governing authority of the MN-S. It is comprised of the Local Presidents, the Provincial Métis Council, four representative of the Métis Women of Saskatchewan, and four representatives from the Provincial Métis Youth Council. The MNLA, based on the recommendations of the Provincial Métis Council, can enact Legislation and appoint Commissions, Committees or other subsidiary bodies in order to effectively carry out the activities and functions of the Organization. Budgets are determined by the recommendation of the Provincial Métis Council.

- Article 3: Provincial Métis Council. The Provincial Métis Council (PMC) is made up of the Regional Representatives, the Executive, and one representative from each of the Métis Women of Saskatchewan and the Provincial Métis Youth Council. The Treasurer sits on the PMC. The PMC forms the cabinet and is responsible for the portfolios to be assigned and recommended (by the President) and is responsible for ensuring that the affiliates, departments, programs and services covered by their portfolios are running smoothly and have the necessary resources.

- Article 4: Executive. There are 4 executive members of the MNLA who are elected province-wide. They are elected for a term of three years. The President of the MNLA is the head of the Executive and chief political spokesperson for the Organization.

- Article 5: Regions. There are 12 regions represented. The regions are governed by a Regional Council composed of the Presidents of each Local and an elected representative elected from the region, to act as chair of the Regional Council, and bring regional matters the provincial table.

- Article 6: Urban Councils. Under this article, is the establishment of Métis Urban Self-Government Councils in Saskatchewan and supports for the North West Saskatchewan Métis Council to develop governance for northern Métis Communities.

- Article 7: Locals. The Locals in each community form the basic foundation of the Organization. Locals must have a minimum of nine members.

- Article 8: Elections. You must be 16 years of age to vote. Under this article, the terms of who is elected and by whom is outlined. It also states that the election must take place every four years.

- Article 9: Establishes the Head Office of the MN-S in Saskatoon.

- Article 10: Citizenship. Using the MNC’s definitions (below), the provincial registry is administered by the MN-S Secretary.

- Métis means a person, who self identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation Ancestry and is accepted by the Métis Nation.

- “Historic Métis Nation” means the Aboriginal people then known as Métis or Half-breeds who resided in the Historic Métis Nation Homeland.

- “Historic Métis Nation Homeland” means the area of west central North America used and occupied as the traditional territory of the Métis or Half-breeds as they were known.

- “Métis Nation” means the Aboriginal people descended from the Historic Métis Nation which is now comprised of all Métis Nation citizens and is one of the “aboriginal peoples of Canada: within the meaning of s.35 of the Constitution Act 1982.”

- “Distinct from other Aboriginal peoples” means distinct for culture and nationhood purposes.

- Article 11: General Assembly. Local members that meet once a year convened by the MNLA to discuss, clarify, vote on and ratify amendments to the Constitution.

- Article 12: Senate, Women and Youth. The Senate is equally represented by male and female. Appointments to the senate are indicated. (There is a senate act, on MNS website). The youth and women seats at the PMC and MNLA are established.

- Article 13: States the Métis are seeking self-governance and sets out a requirement of all officers to swear allegiance to the Métis People and the Métis Nation, but also allows any Provincial Métis Council or Legislative member to seek office in the provincial or federal governments of Canada.

- Article 14: Affiliates. This section addresses affiliates within the MN-S and how the boards of the affiliates are comprised of the political body

- Article 14 (A): Secretariat. Non-profit incorporated body for the purpose of carrying out administrative duties of the MN-S. The board (PMC) that are elected are the directors of the Secretariat.

- Article 15: Amending Formula. This Constitution can only be amended by the majority of three quarters of the members of the MNLA and ratified by three quarters of the members of the General Assembly. Proposed amendments must be registered with the MN-S head office 30 days prior to the sitting of the MNLA. If registered, all proposed amendments must be registered 14 days prior to the first sitting of the MNLA.

- Article 16: How this Constitution takes effect and how it repeals previous legislation is articulated.

- Article 17: Special Election for 2007. This was a special previous added for this particular time. Since this time, and Elections Act has been enacted (passed and ratified at the MNLA).

Do you believe that the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan constitution reflects true self-governance?

Complete the class poll below by voting “yes” or “no”.

You can see the results below.

Some Problems in Métis Governance Structures

The Métis Electoral Consultation Panel, headed by Maria Campbell, issued its report, Métis Governance in Saskatchewan for the 21st Century, on problems in the Métis governance structure in 2006.

The report identified four types of problems with the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan Governance Institutions, which include structural, functional, operational and financial. These problems affect the provincial, regional and local levels:

- The Functional Problems in the MN-S seem to focus on the Senate and General Assembly. The issues involving the Senate and General Assembly are whether they are or not performing their duties, and some participants believe that they are not providing a forum for the Métis to express their views.

a.) Related to this observation, as of 2017, the Senate was only operating in a ceremonial role. This has led to some concerns about balance of power within a major branch of the MN-S government. - The Operational Problems in the MN-S were found on all levels: provincial, regional and local. The 2006 report found participants were not following rules and regulations that have been set by the MN-S. Also, participants claim that they are not given sufficient information regarding functions, regulations, decision-making processes of those institutions, and the roles and responsibilities of the elected.

- There have been communication problems identified between officials and the Métis People. It has also been noted that there are insufficient human and financial resources. The report identified that a needed reforms include (i) a well-advertised General Assembly to be held every year, (ii) more opportunities for Métis people to voice concerns, and (iii) clear rules for officials to abide by.

- The last identified problem was the financial challenges in the MN-S. There are insufficient financial resources at the provincial, regional and local levels, but most of the financial resources are being largely distributed at the provincial level. It is recommended that increased funding from both federal and provincial governments needs to be distributed equally for the benefit of the Métis people.

a.) As of 2017, there is a new five-year infusion of operating funds that hopes to address the financial challenges identified above.

Which governance problem requires the most urgent reform?

Complete the class poll shown below.

You can see the results below.

After years of political infighting, in March 2015 MN-S officially closed operations. Years of internal political strife within the institution had resulted in a failure of the Provincial Métis Council (PMS) to hold meetings, and a provincial legislative assembly had not been held since 2010. Due to a failure to uphold these institutional requirements for receiving funding (defined by hosting two legislative assemblies per annum), the federal government froze MN-S funding in November 2014. Without funding, the MN-S was unable to operate, and used the remainder of their financial resources to pay rent to the building that housed the registries of Métis peoples and citizenship records. This closure meant that Métis persons in Saskatchewan no longer had an official venue in which to apply for membership, a challenge for individuals who relied on membership proof to access particular benefits, such as scholarship or bursary opportunities.

In January 2016, federal representatives met in Saskatoon with MN-S leadership to discuss requirements for implementing a new funding agreement. The most important component will be the scheduling and implementation of an election for the MN-S to restore legitimacy of Métis political leadership. In the interim, the federal government is working with a third-party manager who will oversee financial and operational components of the MN-S. This will include the back pay of rent and ensuring that the registry of Métis citizens is properly preserved. Despite challenges experienced by the MN-S – many of which stem from issues within the constitution – many parties involved are optimistic that the MN-S can work to re-establish successful governing practices.

In July of 2017, a MNLA was held in Yorkton, SK to set a date for an election. Due to unforeseen circumstances, the election was delayed and a second MNLA in February 2017, was held in Saskatoon, SK. The election took place May 23, 2017, and eleven representatives (new to the organization) were elected out of a possible 16 positions. As for undetermined seats, the Women’s seat and Youth seat at the PMC are not determined during the regular election. In a few short months, the MN-S has worked to rebuild the Nation and engage in government relationship-building.

This speech was presented February 19, 2017 in Saskatoon to the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan AGM following the MNLA. In it, Métis leader Frank Tomkins (son of Peter Tomkins) discusses why section 35 rights are important to Métis People, and how he was sent to England to petition the inclusion of Métis in the 1982 Constitutional revisions.

Self Test and Answers

Quiz yourself by writing down responses to each of these questions below. When finished, click each question to reveal the suggested answer. Doing the Self-Test in this way will help you prepare for the Midterms and Final Exam.

Métis peoples are individuals and groups who claim ancestry to children of Aboriginal women and European fur traders. They have claim to Aboriginal rights under section 35 of the Constitution, and also possess connections to a unique cultural history.

MN-S is comprised of a General Assembly (all members of local and regional councils and represented through 12 regional directors), but the Métis Nation Legislative Assembly (the main political organization) is comprised of the regional director representatives, the Métis Youth Council, the Métis Women Society, and the Executive. The MN-S Inc. is responsible for coordination with the provincial government, and program direction and funding coordination for local and regional groups happens through both local councils.

The Métis Act established the MN-S Inc. as the governing liaison body between the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan membership and the provincial government. The Constitution of the MN-S dictates the terms and mandates upon which the organization strives to govern.

Governance issues faced by the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan include concerns about management and leadership accountability, transparency, and communication with the general membership. Some of these issues are related to a lack of funding in administrative staff, vague management policies, and an overall lack of provincial and federal funding for this organization.

Legally, the R. v. Powely case set up precedent for whom can be considered Métis – it requires a claim to a modern Métis group with historical Métis cultural development and a recognition/acceptance from the group as a Métis member. This was established in 2003 as a mechanism for who could claim section 35 Aboriginal rights as a non-Status/Métis individual. The Daniels v. Canada Supreme Court of Canada ruling also affirmed that Métis People should be considered “Indian” as the term is used under section 91 (24) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

Glossary

Daniels v. Canada 2016: A Supreme Court of Canada ruling that established Métis and non-status Indians should be considered “Indians” as the term is used in s. 91 (24) of the Constitution Act, 1867

Southern Inuit (Newfoundland and Labrador): Southern Inuit, distinct from the Inuit and Innu communities, are descendants of Europeans and Indigenous groups in Labrador. They are represented by the NunatuKavut Community Council and are attempting to have their Aboriginal status recognized by provincial and federal governments in Canada (Heritage Newfoundland).

Métis Nation-Saskatchewan (MN-S): The provincial governing and regulating body made of members who self-identify as Métis and are culturally accepted through local or regional councils as members of the Métis community.

Métis Act 2002: Sets out the constitutional structure and recognition of the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan Inc. and the processes for cooperation of this body with the provincial government.

R. v. Powley: A 2003 Supreme Court case that set precedent for Métis hunting rights to be recognized as legitimate Aboriginal hunting rights under section 35 of the Constitution Act. It also provides a set of guidelines to help determine who can legally be a claimant to section 35 rights as a Métis person.

Section 91 (24) Constitution Act 1867: Stipulates that the federal government has exclusive legislative authority over “Indians and lands reserved for Indians”. This constitutional authority does not translate into a legal duty to act.

References

Anderson, Chris. “I’m Metis, What’s your excuse?”: On the optics and the Ethics of the Misrecognition of Metis in Canada. Aboriginal policy studies. Vol 1 (2) 2011, pp. 161-165.

Chartrand, Paul A.H. (ed.) (2002). Who are Canada's Aboriginal Peoples? Saskatoon, SK: Purich Publishing.

Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. “Métis and Non-Status Indians”. Available online at http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100014271/1100100014275 (last retrieved Jan. 01, 2014)

Métis Electoral Consultation Panel. (2006). Métis Governance in Saskatchewan for the 21st Century: Views and Visions of the Métis People, A Report Prepared by the Métis Electoral Consultation Panel, submitted to the Saskatchewan Minister of First Nations and Métis Relations, 2006, Appendix 4.3: Constitution of the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan pp 197-208. The entire report is available online at http://epub.sub.uni-hamburg.de/epub/volltexte/2012/15312/pdf/ElectoralConsultRpt.pdf

Métis Nation of Alberta. “Who are the Métis?” Available online at http://www.albertametis.com/MNAHome/MNA2/MNA-Who2.aspx

Newfoundland Heritage. “Aboriginal Peoples.” Available online at: http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/aboriginal/aboriginal-peoples-introduction.php

Peterson, Jacqueline and Jennifer S.H. Brown. (1985). The New Peoples, Being and Becoming Métis in North America. Winnipeg, MB: The University of Manitoba Press.

Supreme Court of Canada. (2016). Daniels v. Canada. Available: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/15858/index.do

Sprague, D.N. (1988). Canada and the Métis 1869-1885. Waterloo, ON: Wilfred Laurier Press.

Statistics Canada. (2011). “Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis, and Inuit. Available online at http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-011-x/99-011-x2011001-eng.cfm#a4

Recommended Readings

Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied Research. “The Métis Museum.” Available at: http://www.metismuseum.ca/

The Métis National Council. Available at: http://www.metisnation.ca/

Métis Culture & Heritage Resource Centre Inc. (MCHRC) http://www.metisresourcecentre.mb.ca/

The Métis Nation-Saskatchewan. Available at: http://metisnationsk.com/

Marcel Guay. The Métis. [PDF in Canvas]

Marcel Guay. Who Are the Métis? [PDF in Canvas]

Marcel Guay. Métis Groups. [PDF in Canvas]

Janique Dubois and Kelly Saunders. "Rebuilding Indigenous nations through constitutional development: a case study of the Metis in Canada" Nations and Nationalism 23 (4) 2017, 878-901. Available at https://library.usask.ca/scripts/remote?URL=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nana.12312