CONSTELLATIONS

Integral Navigation Tools

By: Thanh Hang Dao, Josh Edzards & Diane Meagan Ong

Constellations are tools that have had many various roles throughout the years. Some of those roles have included being a physical symbol for different religions by representing their gods, providing a calendar for farming and being an important cultural mark as each culture would have differing stories or interpretations of the constellations. One of the most important roles that constellations have been used for is navigation. Many different cultures have used the night sky to navigate throughout history. The night sky has impacted navigation and how scientists have frequently used the night sky as a tool.

Definition of Navigation

In ancient times, humanity did not have advanced location tracking devices like GPS to help with navigation; therefore, they utilized other navigational aids such as the relative positions of constellations, land, air, animals, waves, currents and winds.1 According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary the term navigation means “the science of getting ships, aircraft, or spacecraft from place to place, especially: the method of determining position, course and distance travelled.”2 It was common in ancient times to use certain tools or means for navigation. Therefore, in ancient times, the first sailors kept track of the coast. The Greeks may have followed clouds, which was over the land, guiding them on their path from one island to the next. The Phoenicians found that the sun was also useful for navigation by knowing that it rises in the east, sets in the west and reaches its highest point in the south.3 The sky, whether that be the night sky or the day sky, has always played an important role in navigation.

Ancient Navigation Tools

The Mariner’s Astrolabe is an ancient tool that was invented in ancient Greece by Hipparchus, an astronomer and mathematician.4 It was used to measure the height of the sun or star above the horizon in order to find the latitude. By knowing the latitude, it was possible for navigators to determine the course; therefore, they sailed “east or west along it to reach their destination”.3 However, the use of the mariner’s Astrolabe was not always accurate because it was difficult to handle on a “rolling ship and in high winds”.3 Subsequently, it could result in an error, leading the ship off the course.3 Therefore, the Astrolabe was “replaced by more accurate instruments such as quadrants and sextants”.5 This is one example of how the night sky was used in navigation. The sextant is shown in Figure 1 by using the sun as a reference.

Figure 1: Using the sextant to measure the altitude of the Sun above the horizon. Credits to: Wikipedia

Figure 2: A simple dry magnetic portable compass. Credits to: Wikipedia

The most well-known means of navigation is the magnetic compass (seen in Figure 2), which was invented during the third millennium B.C. by the Chinese people.1 The Earth’s surface is surrounded by an invisible magnetic field. Therefore, magnetic objects, such as a compass, align with the north-south axis according to the north and south poles that are also aligned with the earth’s axis.6 By relying on these natural forces, they were able to navigate easily through the sea. In addition, celestial navigation is an ability that was practised long before humans roamed the Earth. For example, seals navigate by means of identifying celestial objects in the day or night sky. The skill of using celestial objects, especially stars, was employed by navigators to keep track of a ship’s course. This ability is dated back to the 8th century BCE or even before that. It is said that “the original sources are thought to originate from the Bronze Age”7 which was used by the Minoans of Crete. The Phainomena, the first detailed description of the “position of constellation[s] and their order of rising and setting,” was published by the Greek poet Aratus of Soli around 275 BCE.7 With all of these key navigational tools from the past, the stars have played a critical role in how humans have navigated throughout history.

Definition of Constellations

The definition of a constellation, according to the Oxford dictionary, is “a group of stars forming a recognizable pattern that is traditionally named after its apparent form or identifies with a mythological figure”.8 A constellation maps out the celestial sphere by the specifically defined region of the sky.

Originally, these constellations were defined by the ancient Greeks by the shapes made by their star patterns.9 These star patterns of the brightest stars in the sky represented mythical heroes. In addition, the constellations were subsequently used in story-telling and handed down from generation to generation. Astronomers during the early 20th century decided to have an official set of constellation boundaries.9 Therefore, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) recognizes 88 constellations; 3610 are visible from the northern hemisphere and 5211 can be seen from the southern hemisphere. Furthermore, it should be noted that the IAU identifies a constellation by its sky coordinates, meaning that its boundaries are defined by coordinates and not by its pattern. Therefore, the IAU states that “the same constellation may have several variants in its representation”.9 Throughout history, constellations have been used for navigation in the study of astronomy, regardless of whether they had official boundaries or not.

The first time a constellation was recorded was around 17300 years ago. According to archaeological studies, they have found astronomical markings painted on the wall at Lascaux in southern France. Most star constellations from the north of the horizon, forty-eight in total, were recorded in the “seventh and eighth books of Claudius Ptolemy’s Almagest”.9 During the 16th and 17th century AD, new constellations were added to the already known ones by European astronomers and celestial cartographers. These new constellations mostly were found while exploring the southern hemisphere,9 which shows that the physical location of an individual will affect the use of the night sky.

An asterism is a pattern of stars that are not designated constellations. However, an asterism might be part of a constellation, such as the Big Dipper, which is composed of the seven brightest stars in the Ursa Major constellation.12 In addition, an asterism might be made up of stars from different constellations.12 It should be noted that it is not possible for an observer to see all the 88 constellations only from one location of Earth.13 Some of the southern constellations are visible from the northern hemisphere, yet it depends on the time of the year. For instance, Scorpius can be seen over the southern horizon in the summer, whereas others might never rise over the horizon. An example of this is the Crux, also known as the Southern Cross, which cannot be viewed from most locations of the northern hemisphere. Correspondingly, the constellation Ursa Minor is not visible from most places south of the equator13 because the location of an individual affects their view and use of the night sky.

Northern Constellations

In the northern celestial hemisphere, located north of the celestial equator, the 36 known constellations are visible. The northern hemisphere can be divided into four quadrants, NQ1, NQ2, NQ3, and NQ4 in which the 36 constellations can be found.13

Figure 3: Northern star constellations. Image captured with Stellarium.

|

Ursa Major Some important northern constellations are the Ursa Major, which is shown in Figure 4, and the Ursa Minor, which are both constellations by which one is able to identify the Polaris. The Ursa Major literally means “The Great Bear” and is the third largest constellation in the night sky. It can be seen almost every night from anywhere in the northern hemisphere.14 Ursa Major is most commonly known due to the main seven stars that form the Big Dipper. The Big Dipper is an asterism, and the four stars create the “bowl,” and the three additional stars form the “handle.” |

|

Ursa Minor Similarly to the Ursa Major, four of Ursa Minor’s stars (present in Figure 5) create the “bowl” and the other three form the “handle”; hence, this constellation is termed “The Little Dipper” as its shape is a smaller version of the Big Dipper. Moreover, the Ursa Minor “contains the north celestial pole, which lies within 1° of the conveniently placed 2nd-magnitude star” that is known as the Polaris.14 These are some of the important constellations that can be seen in the Northern Hemisphere that an individual in the Northern Hemisphere would use for navigation.15 |

Figure 4: Ursa Major. Image captured with Stellarium. |

Figure 5: Ursa Minor. Image captured with Stellarium. |

Navigation in the Northern Hemisphere

The use of star constellations could be described as using a pin needle as a marking point for navigation. For example, in the northern hemisphere, there is one star which shines brightly, the North Star or Polaris. By recognizing this star, one can navigate their own course. The North Star is the star almost above the North Pole which can be used for navigation because it functions as a marking point that one can use to identify north. It serves as a marking point because even as stars move through the sky throughout the night, the North Star stays relatively in the same position. However, it is necessary to be able to find the North Star to be able to use the night sky for navigation. This is done by assessing the constellations and finding the Big Dipper. The Plough is a part of the constellation Ursa Major.16 By finding the Plough one can locate the North Star by looking at the two pointers. The two pointers are called Dubhe and Merak, which are on the edge of the Big Dipper’s “bowl”. The two pointers indicate the direction as they point towards the North Star, Polaris. Polaris is five times the distance between Dubhe and Merak.17

Another way to navigate through the Night Sky is by finding Ursa Minor, which is also called the Little Dipper. The seven brightest stars form the same shape as the Big Dipper but in a smaller version. At the end of the “handle” is northern Polaris (α Ursae Minoris). Since the stars are challenging to notice because of their magnitude it is preferable to use the first option to navigate.14 This gives a picture of a few ways that an individual in the Northern Hemisphere would use the night sky to navigate, which differs from an individual in the Southern Hemisphere. Both methods are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Find North with the Stars – Polaris & Ursa Major – Celestial Navigation. Credits to: AlfieAesthetics

Southern Constellations

The southern hemisphere can be divided into four quadrants, SQ1, SQ2, SQ3, and SQ4 in which the 52 constellations can be found.11

Figure 7: Southern star constellations. Image captured with Stellarium.

Figure 8: Crux and Centaurus. Image captured with Stellarium.

Southern Cross, Crux

The Crux (shown in Figure 8), also known as the Southern Cross, is the smallest constellation with only 6° in any hemisphere.18 The Mediterranean discovered the constellation already in ancient time and so it was a star that was known by the Greek astronomers. The Greek astronomers regarded the Crux as a part of the Centaurus, which was separate to its own in the 16th century. The star constellation is placed in the Milky way.14

Centaurus

Centaurus (seen in Figure 8), which describes half a horse with a human body, is a mythical creature of the Greeks. A line through α and β Centauri points to the Crux. The constellation is also located in a milky way. Alpha Centauri is the third brightest star that can be seen from Earth. With a magnitude of -0.27, the star is easily detected.14

Figure 9: Cruz Falsa (False Cross). Credits to: Wikipedia

False Cross

The False Cross is not a star constellation, but it could be mixed up as a constellation. Since the False Cross both looks similar and is close to the Southern Cross, the False Cross and the Southern Cross are easily confused with each other. The stars ι and ε Carinae, together with the stars κ and δ Velorum, form the shape of the False Cross. 14 These are some important constellations in the Southern Hemisphere that an individual in the Southern Hemisphere would use for navigation. This would differ from an individual in the Northern Hemisphere because the physical location of an individual affects their use of the night sky for navigation.

Navigation in the Southern Hemisphere

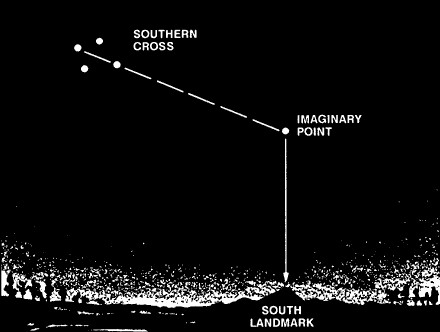

The use of the northern Polaris in the Southern Hemisphere is obviously pointless since it is not possible to find the northern Polaris there. In this case, it is necessary to orientate by another star. The Polaris Australis was named in the 1700s, and is also known as Sigma Octantis, and is only 1.05 degrees off the south celestial pole. Therefore, this star is significantly close to the south pole; thus, the Polaris Australis is an anchor point for navigation. However, with its magnitude of 3.76 the star is not easy to find.19 Therefore, it is effective to find a brighter star constellation in order to locate the Polaris Australis. The Crux, mostly known under the name Southern Cross, is a good tool to find the Sigma Octantis. The constellation is small but indeed simple to discover. Its long axis, from γ (Gacrux) to α (Acrux) point towards the south celestial pole.14 Figure 10 visualize the method. The distance between southern Polaris and the two pointers is around five times the length of the pointers. To avoid using the False Cross, which looks like the Southern Cross, it is important to look for the brightest two stars next to the crosses, then they are brighter at the Southern Cross. Also, the Southern Cross is smaller than the False Cross. The False Cross points in a completely different direction and is not adapted to functioning as navigation.18

The difference in an individual using the North Star or the Polaris Australis for their navigation relies on their physical location. However, whichever star one uses, it is clear how important constellations are in navigation in the study of astronomy and in general navigation.

Figure 10: Find South with the Stars – Southern Cross – Celestial Navigation. Credits to: Wikipedia

Conclusion

In the day and age of technology that allows an individual to have navigation devices right at the tip of their fingers through smartphones and GPS, it is hard to understand the critical role that constellations have played in the use of navigation in the study of astronomy and in general. However, in reading the use of ancient navigational tools that utilized the use of the night sky, hopefully, that has allowed for a deeper appreciation of how the night sky and constellations, in particular, has contributed and played a crucial role in navigation. The following videoSo, hopefully, the next time you need to figure out where north or south is, instead of pulling out your phone and bringing up your compass app, you will be tempted to look up at the night sky and take part in using the constellations for navigation. And in doing so, hopefully, it will give you a deeper appreciation for the integral role that constellations and the night sky has played in navigation throughout the ages.

The following video is a good summary of how to navigate by using the night sky:

Video 1: How to Navigate Using the Stars. Credits to: Atlas Pro

References

1Nova. Secrets of Ancient Navigators. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/secrets-of-ancient-navigators/ (Accessed 22 January 2019).

2Merriam-Webster. Definition of navigation. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/navigation (Accessed 28 February 2019).

3The Mariners’ Museum & Park. Mariner’s Astrolabe. https://exploration.marinersmuseum.org/object/astrolabe/ (Accessed 28 February 2019).

4T. Kusky and K. Cullen, Encyclopedia Of Earth And Space Science (2010).

5H. Selin, Encyclopedia Of The History Of Science, Technology, And Medicine In Non-Western Cultures (1997).

6D. Geary, Using a Map and Compass (Stackpole Books, Pennsylvania, 1995), p. 5.

7M. Neilbock, AstroEDU, 1645 (2017).

8Oxforddictionary. Definition of constellation. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/constellation (Accessed 27 February 2019).

9IAU. The Constellations: Origin of the Constellations. https://www.iau.org/public/themes/constellations/ (Accessed 31 January 2019).

10Constellation Guide. Northern Constellations. https://www.constellation-guide.com/constellation-map/northern-constellations/ (Accessed 31 January 2019).

11Constellation Guide. Southern Constellations. https://www.constellation-guide.com/constellation-map/southern-constellations/ (Accessed 31 January 2019).

12Maria Temming. What are constellations? https://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-resources/exactly-constellations/ (Accessed 27 February 2019).

13Constellation Guide. Constellation Map.https://www.constellation-guide.com/constellation-map/ (Accessed 27 February 2019).

14I. Ridpath and W. Tirion, Stars and Planets: The Complete Guide to the Stars, Constellations, and the Solar System (Princeton University Press, North America ,2017).

15G. Chaple, Learn the constellations, http://www.astronomy.com/observing/astro-for-kids/2008/03/learn-the-constellations (Accessed 27 February 2019).

16Phil Plait. The Big Dipper like you’ve never seen it before.https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/big-dipper-youve-never-seen-it (Accessed 29 January 2019).

17Phil Plait. Astrophoto: The Big Dipper Over Chile … Barely. https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/astrophoto-big-dipper-over-chilebarely (Accessed 29 January 2019).

18G.D. Almeida, Navigating the Night Sky: How to Identify the Stars and Constellations (Springer, 2004), p. 120-122.

19J. B. Kaler, The hundred greatest stars (Copernicus Books, United States, 2002).