by Chris Chan

Head of Information Services at Hong Kong Baptist University Library

Part1: 7 May 2019

I am writing this first part of the blog post from my comfortable hotel room in downtown Minneapolis, where I have arrived ahead of the LOEX Annual Conference that will start at the end of the week. Navigating US Immigration at Chicago after the longest flight I have ever taken (15 hours!!) has taken its toll, but I am hoping that arriving a few days early will give me a chance to more or less recover from jet lag ahead of the event starting on the 9th.

The time will also allow me to put the finishing touches to my breakout session presentation. I’ll be talking about the efforts we have been making at HKBU Library to ensure our graduate students are equipped with the scholarly communication knowledge and skills that they will need to be successful researchers. For several years we have had required library workshops for our research students that covered the basics of scholarly publishing. These sessions also sought to raise awareness of current issues in scholarly communication, such as open access and altmetrics. Although student feedback has generally been positive, we found it challenging to design sessions that were suitable for both novice researchers and those graduate students that already had prior publication experience. We also wanted to better assess the extent to which students were achieving the learning outcomes of the session, as the results of relatively simple in-class exercises could tell us only so much.

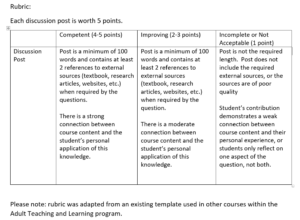

Our new approach, launched this year, has been to adapt our workshop content into a modular online course. The course is designed so that students can skip content that they are already familiar with. To fulfill the new course requirement, students need to achieve a passing grade on a short online quiz assessing their knowledge of course content. In my presentation, I’ll be sharing the results from our first year of implementation. I’m also hoping to find out what approaches other institutions are taking, and to this end I’ll be using Mentimeter for the entire presentation. I’m a little nervous about having to rely on an online service, but fingers crossed that it runs smoothly. Another benefit is that I will be able to share the results in the second part of this blog post.

Part 2: 11 May 2019

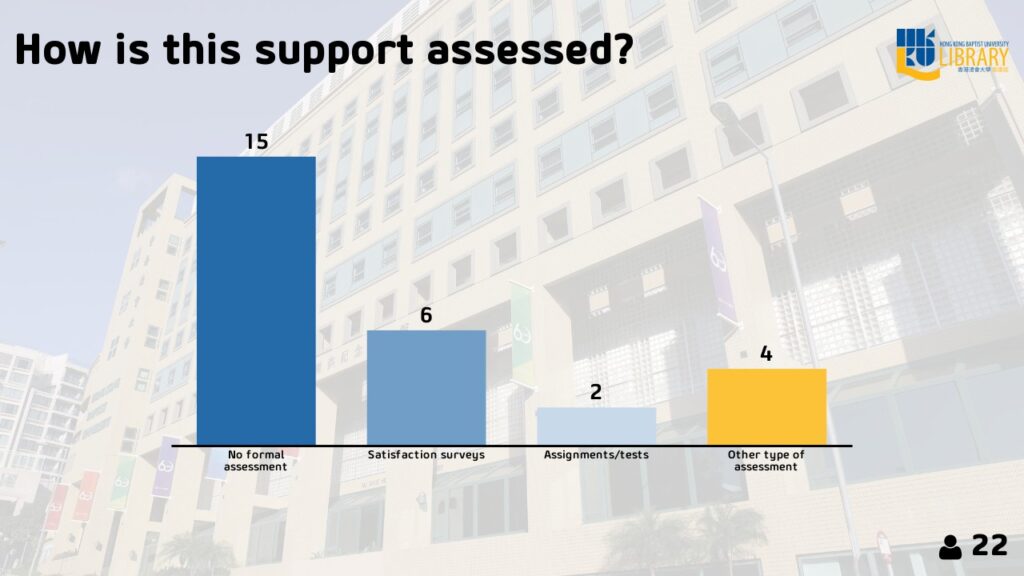

All done! The conference was excellent – there were so many things that I will be bringing back to my own institution. As for my own presentation, everything went smoothly in technological terms. Mentimeter worked as advertised, and having the interactive segments seemed to help keep things interesting for the audience. Their responses were incorporated into the presentation material in real-time. For example, the results for this question supported a point that I had seen in the literature – that this type of support for graduate students is often not formally assessed (the full question was “How is support for graduate student scholarly communication skill development assessed at your institution?”):

I also used the built-in quiz function in Mentimeter to showcase some of the questions that we use to assess the student learning. Shout out to Marcela for winning!

You can view the full presentation (including the results of the audience voting) here: https://www.mentimeter.com/s/e1451a492dd1d3a21747448a6ff3ce70

This article gives the views of the author and not necessarily the views the Centre for Evidence Based Library and Information Practice or the University Library, University of Saskatchewan.