Thursday, January 18th, 2018...4:33 pm

The Rise of Middle English – with a little help from the French

April Anderson

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, the English language underwent a drastic change. It was at this time that the shift from Old English to Middle English began to occur. The Middle English period saw many new linguistic phenomena take hold around 1150, and continue to shape this new form of English until about 1500 (OED s.v. Middle English, n, sense A). However, there is evidence that the catalyst for these changes began in the years between 1066 and 1200 (Baugh and Cable 98), leading to phonological and lexical changes in the English language.

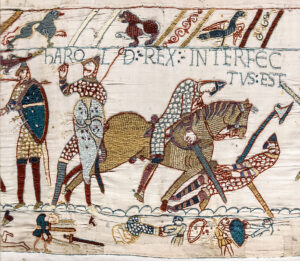

Figure 1. Bayeux Tapestry – Scene 57: the death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

After King Harold was killed during the Battle of Hastings in 1066 (see fig. 1), much of the English nobility was replaced by the Normans. This was because a majority of King Harold’s nobles had either been killed in battle or perceived as traitors, leaving many positions of authority available for the taking (Baugh and Cable 101). These positions were inevitably filled by the Norman nobility because they remained noblemen under the new king, William. Because they gradually took over these positions of power, the Normans gained more control in areas of legislation. Despite the presence of the French in these new governments, many of the new nobility did not live in England (Liu C.39). Due to their absence, many of the English-speaking citizens would not learn French right away.

After 1066, English became the language of the working class, while French became the language of the government (Ellis 28). However, neither party was very quick to learn or use the other’s language. With the French in control, there was a significant language barrier between the upper and lower classes. The lower class, dealing in their own personal affairs saw little reason to learn French, and the upper class, with many of them residing outside of England had little reason to learn English (Liu C.39). Eventually however, English citizens dealing with French nobility needed to communicate with their superiors, so a multitude of French words regarding governance started entering the English lexicon (Ellis 28), such as duke (OED s.v. duke, n, sense 2a) and council (OED s.v. council, n, sense 2). French additions to the lexicon persisted even after 1200, evident when considering the ways in which people spoke about their livestock. The Anglo-Saxon words cow, sheep, and pig from Old English are still used today when referring to a living animal, but when referring to the meat from said animal, the French terms beef, mutton, and pork, respectively, are used (Ellis 29). Although they were not added between 1066 and 1200, the addition of these French words to the English lexicon still demonstrates the influence that French had over English due to the power that the French gained during this period.

A primary component of a language is how words are pronounced and what sounds are used to pronounce them. Both French and English have certain sounds that are native in one language, but not in the other. As more French words began to arise in the English lexicon, some of these different phonological sounds accompanied the borrowed words. The diphthongs in the words price, out, and boil were introduced and the distinction between voiced and voiceless fricatives such as the voiced /v/ and voiceless /f/ became relevant to English because of French loanwords adopted by English speakers (Liu C.41).

The arrival of the French under William the Conqueror saw various additions to the English language, many of which occurred due to government positions being filled by the Norman nobility. The communication between a French-speaking upper class and an English-speaking lower class caused the two languages to interact, adding new words and word sounds into the English language. The changes that occurred in English between 1066 and 1200 were the beginnings of Middle English and the start of a movement that would greatly contribute to the development of English as a whole.

Works Cited

Baugh, Albert C., and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. Routledge. 2002.

Ellis, Sian. “How the Normans changed England: what the conquest brought to the kingdom.” British Heritage, Sept. 2012, p. 44+. Canadian Periodicals Index Quarterly, http://link.galegroup.com.cyber.usask.ca/apps/doc/A295551047/CPI?u=usaskmain&sid=CPI&xid=5f7bb82b. Accessed 30 Dec. 2017.

[OED]. Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press, June 2017 http://www.oed.com.cyber.usask.ca/view/Entry/256139. Accessed 28 December 2017.Liu, Yin. English in Time: Course Notes for English 290.6. University of Saskatchewan. 2017.

Comments are closed.