Monday, April 13th, 2020

The Day the Vikings Came: Old Norse and its Impact on the English Language

Ashley Sharp

Photo by PxHere: Viking wood carving. https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1376595

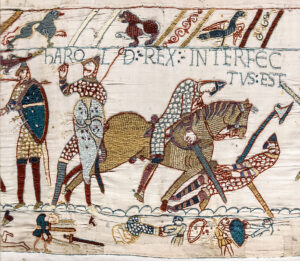

The Viking presence within England had a great impact on the English language from the year 800 to the year 1100. This impact can be seen on the lexicon and the loss of inflection. English has had a great number of lexical borrowings from other languages such as French and Latin but often overlooked is the impact of Old Norse on the language. Old Norse has arguably had one of the greatest impacts on English. Being a Germanic language, Old Norse is very similar to Old English. ON is a North Germanic language whereas OE is a West Germanic language that are both within the Proto-Germanic family (Liu D.20). Although many words of both languages are seemingly identical to one another, the inflection and pronunciation of the language differed slightly (Gramley 51). It is most likely that speakers from both would have roughly understood one another.

Click here to read more