Monday, February 17th, 2020...9:56 pm

Hey, you people, what are we going to do about it?

Bryce Bulgis1

“I definitely won’t say ‘they’ or ‘them’ for one person. I speak English, so ‘it’ will do.”

This quote, an excerpt from a texting conversation,2 comes from one of my oldest friends from grade school, a man named Bob.3 Knowing me as an English scholar, someone well versed with the intricacies of our lingua franca, you may be surprised to learn that Bob is actually my best friend, ha ha. You see, Bob and I sometimes clash over certain topics, many of which centre around how people use language to describe certain phenomena. And we most recently clashed over the usage of the third-person gender-neutral singular pronoun it when referring to people, particularly transgendered people. Bob thinks that “[t]ransgenderism is just another thing that people do . . . . They have a mental disorder and I hope they can get help.” And what’s his solution to when they face scrutiny in public? To “do what we all do. If you go somewhere that people don’t accept you, stop going there. Only go places where people don’t care about you . . . . It’s as simple as that.” However, being transgendered isn’t a phase, a joke, nor an act; it’s who these people are, and their pleas to seek acceptance and equality in society is anything but simple as they and their allies advocate for society to use language to recognize them as people.4

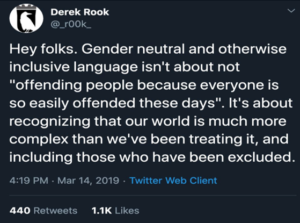

Bob believes that living in a world plagued by pronoun controversies and having to yield to people’s pronoun preferences is a first world problem. But the issue with it is that it simply cannot be used as a singular gender-neutral pronoun for people, as the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) lists it as being a derogatory and humourous reference to a person and is a pronoun that is commonly used in children’s language before they learn that it is not appropriate to refer to people (s.v. it, pron., adj., and n.1 sense A, I, 1, a., (a) and (c)). But the OED entry only further proves that anyone who is fluent with English should know that it is used to refer to objects, not people. In fact, if you try to search for controversies involving it being used as a referent for people, you will struggle to find anything at all. The lack of real-world incidents reflects how the English-speaking society just knows to only use it for objects. When I saw the photo, included at the top of my blog,5 I wasn’t surprised to learn that my transgendered friend Logan shared it on her Facebook page to raise awareness for gender-neutral language.6 The photo reflects how our world has never been simple, and our language needs to adapt to embrace the complex people and situations that have previously been excluded. The usage of it suggests a discriminatory labelling of transgendered people, a labelling facilitated by the discourse that transgenderism is a mental illness. Thus, using it implies that one does not consider transgendered people actual people in keeping with the well-established male and female dichotomies that dominate our society.

One such solution to addressing gender-neutral singular entities is to use the third-person gender-neutral subject pronoun they. As my excerpt from my texting conversation with Bob shows (which is seen underneath the photo at the beginning of my blog), there is a misunderstanding between us about the changing status of they, which has traditionally served as a third-person gender-neutral plural subject pronoun. But the historical usage of they, as explained by the OED, illustrates that they was used as a singular pronoun amidst its more extensive usage as a plural pronoun throughout its history, regardless of the gender of its referent (s.v. they, pron., adj., adv., and n. sense A, I, 2). Its historical usage demonstrates that its resurgence as a singular pronoun in modern society isn’t as ungrammatical as some people think; in fact, they is just what gender-neutral people need, since it’s gained the specific purpose of referring to gender-neutral individuals since 2009 (OED s.v. they, pron., adj., adv., and n. sense A, I, 2, c) After all, nothing “may be more personal than the way in which people refer to us through our name and pronouns” (“Talking”), which is exactly why English speakers should be wary of their pronoun usage and never assume the pronoun preference of a person, who probably wouldn’t like it.

Nevertheless, some people may continue to resort to what currently stands as official principles: that transgenderism is indeed a mental disorder, and it shall be used to ostracize these people if they are even considered people at all by the passionately opinionated, ha ha. But every person has a right to be acknowledged and treated like a person no matter what their gender is—let me call that first world virtue in response to Bob’s first world problem stance—and the time is now for us to make spaces for them, which begins with honouring whatever pronouns they use. So what are we going to do about it? Leave it where it belongs: for objects, not people.

A quote for thought:

“Be kind to one another.”

– Ellen DeGeneres

Further Research

Meyer-Bahlburg discusses the issues of classifying transgenderism, part of their Gender Identity Variants (GIVs) conceptualization, as a mental disorder.7 They explain that GIVs in America became associated with mental disorders in 1980 (462), but calls for change since then have resulted in multiple strides forward for transgendered people. Most notably, psychologists have recognized that trans individuals can be “high-functioning and satisfied with their adopted gender” just like any other cisgendered person (463).

And their findings have led nations to take a stand to have transgenderism declassified as a mental disorder. For example, Mexico has called upon the World Health Organization (WHO) to remove transgenderism from its list of medical conditions (“Campaign”). After all, if transgendered people do experience mental distress and dysfunction, it is because of experiences with “‘social rejection and violence’ rather than the experiences of gender itself” (“Campaign”). The American Psychological Association seconds this latter point, yet they acknowledge the disappointing fact that transgenderism is still considered a mental disorder.

But hope remains, as the International Classification of Diseases is continually updating and will change its current classification of gender incongruence as a “gender identity disorder” and remove this label from the list of international mental disorders (American; Global). Furthermore, WHO is overseeing this change, as they plan to move gender incongruence into their sexual health chapter and out of the mental disorder section (Global); these changes would take effect in 2022, if they are approved.

Notes

1 Does the title of this post remind you of another Canadian pronoun controversy? Don Cherry’s you people debacle rocked the nation in November 2019, which sparked a recurring debate about inclusive language and whether or not people nowadays are too sensitive or easily offended. While I do not discuss Cherry’s incident in this blog, I provide the following link if you wish to recall what transpired and the impact that his utterance had on people who felt targeted by it: https://globalnews.ca/news/6157812/don-cherry-you-people-rant-impact/. The implications of Cherry’s utterance parallel the implications of using it to refer to people.

2 More detailed source information for my texting conversation with Bob can be found in Bulgis.

3 Bob is a pseudonym.

4 The history (and future) of transgenderism as a mental disorder is extensive; consult the Further Research section just after this blog for a concise overview of the debate if you would like to learn more.

5 More detailed source information for this image can be found in Logan. However, to ensure Logan’s anonymity, the individual URL was not included in the Works Cited list, and the photo has been cropped to hide Logan’s identity. Basically, only the tweet that Logan shared is viewable in the photo.

6 Logan is a pseudonym.

7 Mental disorder is the term used in psychological medical discourse; in my blog, mental disorder and mental illness are synonymous.

Works Cited

American Psychological Association. “Transgender people, Gender Identity and Gender Expression.” www.apa.org/topics/lgbt/transgender. Accessed 26 Jan. 2020.

Bulgis, Bryce. “Texting Conversation.” 25 Jan. 2020. Facebook Messenger conversation transcription.

“Campaign for WHO to Declassify Transgenderism as a Mental Illness.” Greenleft Weekly, 8 Aug. 2016, www.greenleft.org.au/content/campaign-who-declassify-transgenderism-mental-illness. Accessed 26 Jan. 2020.

Global News. “Being transgender no longer a mental-health condition: WHO.” 21 June, 2018, globalnews.ca/news/4288052/transgender-mental-health-condition/. Accessed 26 Jan. 2020.

Logan. Facebook. 23 Jan. 2020. Accessed 26 Jan. 2020.

Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F. L. “From Mental Disorder to Iatrogenic Hypogonadism: Dilemmas in Conceptualizing Gender Identity Variants as Psychiatric Conditions.” Archives of Sexual Behavior, vol. 39, no. 2, 2010, pp. 461-76. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9532-4.

[OED.] Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford UP, 2020. www.oed.com. Accessed 6 Feb. 2020.“Talking About Pronouns in the Workplace.” Human Rights Campaign, www.hrc.org/resources/talking-about-pronouns-in-the-workplace. Accessed 6 Feb. 2020.

Comments are closed.