The second guest post by practicum student Andrew Moore. Andrew Moore is from Saskatchewan, but decided to move 4000 Kilometers away to become a Librarian. An Alumnus of the University of Saskatchewan (B.A 2011), and a current MLIS Candidate (2016) at Dalhousie University, his interests include cooking, reading and history

Introduction

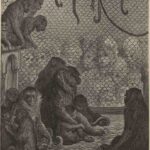

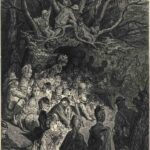

There are some who might argue that because the art in medieval books lacks perspective and that the text is difficult to read, that they are uninteresting. Nothing could be further from the truth! Many medieval manuscripts are full of art that is fantastical, gruesome and occasionally, downright strange. There are few (if any) modern books that use artwork to depict demons menacing and stuffing sinners into the mouth of hell, and fewer still that depict a crowd of men being trampled by the

Beast with seven heads and crowns (of Biblical infamy). And as far as this writer is aware, there exists no modern book that was created specifically for crowned royalty that was also given absurdest illustrations of a hand with a lion’s foot and tail, balancing a chalice, perching atop the full-page illustration (depicted below).

The University Archives and Special Collections have a special treat for lovers of the strange, apocalyptic and unusual, as well as for those fond of medieval art and illustration. The UASC has acquired a rare, beautifully crafted and 100% faithful reproduction of L’Apocalypse 1313, a medieval Apocalypse Manuscript originally owned by the infamous Isabella “The She-Wolf” of France, Queen to Edward II of England.

The manuscript is a recent addition to University Archives and Special Collection’s Rare Book Collection.

So, What the Heck is an Apocalypse Manuscript?

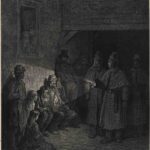

The simple answer is that it is a manuscript that provides both imaginative imagery and commentary on the text and ideas found in the Biblical book of Revelations.

The somewhat longer and more complicated answer lies at the roots of medieval Christianity; books such as L’Apocalypse 1313 are a part of a larger tradition of Biblical exegesis (critical interpretations or explanations of text). Books such as L’Apocalypse 1313 strove to allow their readers to both understand the sometimes difficult theological ground of the Book of Revelations, and to allow the reader to conduct religious meditation on these mysteries.

The genre of Apocalypse manuscripts is one with a fairly long life; examples of the genre appear in Spain, Italy, France, England and Germany. Nor are exegetical manuscripts limited to a particular time-frame; while the genre was most popular in the 12th Century, examples of the genre appear in both early and high medieval Spain, and examples appear in the Low Countries and Germany as late as the 15th Century. Because the Genre of Apocalypse Manuscripts is so broad in both geography and time, a given manuscript can be placed into different ‘families’ that best represent the specific style. The original manuscript and the reproduction of L’Apocalypse 1313 available in Special Collections are examples of the Gothic Anglo-French Apocalypses, which were created in the 13th and 14th Centuries.

Apocalypse Manuscripts such as this represent an important cultural and religious facet of medieval European life, as well as being beautiful, strange artistic works in their own right. The trip to view the original L’Apocalypse in the National Library of France might be beyond the means of many local lovers of rare books and medieval art/manuscripts; fortunately, the trip to view the reproduction is far simpler, and the staff at UASC would be pleased to let those interested discover it for themselves.

About the Manuscript

Because the reproduction of the original L’Apocalypse 1313 is a faithful one, a description of one manuscript also describes the other.

L’Apocalypse 1313 is a small volume; including the bindings, it measures only 23.7 centimetres high, 16.7 centimetres wide and about 6 centimetres thick on average. The book is bound using wooden boards and six ribs. T he ribs, head and tail all have gold fillet adorning them, though this decoration appears to have been added in more historically recent times. The volume consists of 167 folios and two unnumbered leaves.

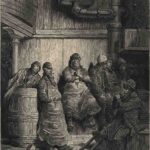

Given the volumes physical size and its patron, it was likely intended to be a non-ceremonial book; that is, it is small enough to be used and carried on a regular basis. This notion of usability is supported by the genre of the volume; exegetical works such as L’Apocalypse were intended to guide readers in contemplative meditation on the allegories of the Book of Revelations.

While Chadewe Colins (discussed below) may have been the primary force behind the work, he is not the only one. The reproduction of the manuscript is accompanied by an excellent, detailed commentary by Moleiro, who identifies five separate scribal hands that took part in the production of the text to the original manuscript.

Even if the modern reader is not given to religious meditation, looking at the reproduction of L’Apocalypse available in Special Collections is still greatly worthwhile, both for the fantastical and often gruesome medieval conception of the end of the world, and to appreciate the tremendous planning and preparation that must have gone into creating such a functional work of art.

About the Author

The scribe to whom the writing of L’Apocalypse 1313 is attributed identifies himself as one Chadewe Colins. Regrettably, as with many people involved in literary pursuits in the Medieval Period, not much more is known about the man. It is probable that he was a man of some degree of learning and artistic skill; the inscription where he identifies himself as the writer of the book also indicates he was the one who illuminated the manuscript.

Moleiro identifies five scribal hands that had a part in the production of the manuscript. Which of these was Colins is unknown, and any information on the identities of the other four scribes is likewise unknown.

About the Patron

According to an inscription in the text, the Manuscript was made for Isabella of France (b.1295- d.1358), the wife and Queen of Edward II (b.1284-d.1327) and the mother of the future Edward III. Isabella was the daughter of King Philip IV “The Fair” of France (b.1268-d.1314), and was one of the most colourful and interesting figures of Late Medieval England.

Isabella was probably literate, and she was certainly cultured. Aside from L’Apocalypse 1313, her collection of books which survived to the modern day include seven other religious texts, eight volumes of romances, a collection of Arthurian legends, and the ‘Isabella Psalter’ (which also contained a bestiary).

Sent to England at the age of 12 to be a child bride to Edward II, her marriage was generally seen to be an unhappy one. She was much dissatisfied with the life at the English court, which was, to her a significant step downward from the vibrant cultural scene in Paris. Additionally, Edward II was a man who tended to be easily swayed by what both Isabella and the great magnates of England saw as bad councillors. Edward consequently ignored his wife, and invested great power in these advisers, first Piers Gaveston, and later Hugh Despenser the Younger.

This proclivity of Edwards to favour what his largest vassals saw as unworthy individuals led inevitably to conflict. English Barons who had long hated Gaveston, captured and executed him in 1312, and it was Isabella who managed to intercede between the King and his Barons, and thus preserve peace.

This changed by 1326. The new royal favourite, Hugh Despenser the younger was also much despised by the great magnates of England, but also by the Queen. In 1326, she led an army from France alongside expatriate Englishman Roger Mortimer (1287-1330), who was also the queen’s lover. Together, they invaded England to get rid of Despenser for good. Despenser was captured by mid-November of that year, tried, and then executed gruesomely by being hanged, drawn and quartered. Edward II was forced to abdicate by his victorious wife and nobility in favour of his son, and died by September of the next year.

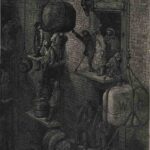

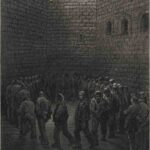

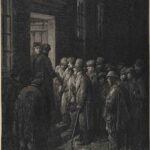

Figure 12- Recto 16 and Verso 17. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Recto 16 depicts the Horsemen of Conquest and War. Verso 17 depicts the Horsemen of Famine and Death. Also depicted are St. John of Patmos (At right, with a scroll), and symbolic versions of the Apostles Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

All was not well in the land, though. Isabella and Mortimer ruled England as regents for the young Edward III, but their profligate spending and an unpopular treaty with the Scottish quickly led to them becoming unpopular in their turn. In September 1330, Edward III led a coup against his own mother and her lover; Mortimer was executed and Isabella was imprisoned.

Isabella did not stay imprisoned for long. In order to preserve her reputation and potential claims on the French Crown, Queen Isabella was allowed to retire from public life, given an annual salary of £3,000 and went to live quietly in the countryside. She lived in this manner until 1358.

Sources

Chadewe Colins (n.d). In Benezeit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved from

http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/benezit/B0003491

Hilton, L. (2008). Queens Consort. London, U.K: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

’Isabella (1295-1358)’ (2004). In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved April 27th, 2015

from http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14484?docPos=5

Klein, P.K. (1992). Introduction: The apocalypse in medieval art. In R.K. Emmerson and Bernard McGinn

(Eds.), The apocalypse in the middle ages. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

McGinn, B. (1992). Introduction: John’s apocalypse and the apocalyptic mentality. In R.K. Emmerson

and Bernard McGinn (Eds.), The apocalypse in the middle ages. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

Plukowski, A. (2003). Apocalyptic Monsters. In B. Bildhauer and R. Mills (Eds.), The Monstrous Middle

Ages. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Weir, A. (2005). Queen Isabella. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.