Wednesday, April 1st, 2020...9:43 pm

“Fire and Fury”: Donald Trump’s “Modern Day” Language

Brandon Fick

After midnight (ET) on May 31, 2017, Donald Trump tweeted: “Despite the constant negative press covfefe” (@realDonaldTrump). The tweet remained on his feed for hours, and even after it was deleted, Trump would not admit it was a misspelling of coverage. In the immediate aftermath, covfefe went viral as a hashtag, meme, and Google search term. There has been a multitude of covfefe merchandise, and a bill in the U.S. House of Representatives requiring preservation of a President’s social media activity even used covfefe as its acronym (Wamsley). This is a prime example of the attention Trump commands. As President of the United States and with seventy-three million Twitter followers, no other person has had such a platform in the history of English. His Twitter use is a matter unto itself, but underlying it is the way he speaks on a daily basis, in unscripted remarks, speeches, and interviews. Trump’s “leadership” is inextricably tied to his language, as whether intentional or not, his vocabulary and syntactic traits resonate with a significant portion of America.

One of Trump’s most infamous statements is this: “North Korea best not make any more threats to the United States. They will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen” (Zeleny et al.). His language is informal and absolute, portraying a complicated geopolitical situation in black and white terms. As reckless and unsophisticated as it seems, it appeals to people dissatisfied with the word salads of polished politicians, and plays into notions of American Exceptionalism. George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” (1946) argues that the “decadence” of modern English often allows politicians to obscure the truth: “In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible… Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging, and sheer cloudy vagueness” (7). Trump rarely allows “decadence” into his speech, and when he does it sounds stilted. Contrasted with previous Presidents, “Trump uses shorter words and a more restricted vocabulary, suggesting that his language will appear familiar to a larger proportion of people” (Hunston). He is a fan of adjectives like big, huge, and beautiful, and tags his political opponents with infantile but effective nicknames like “Crooked Hillary.” Orwell’s essay warns against using the clichés and meaningless metaphors Trump traffics in, yet these seemingly do not damage his standing with his supporters. If anything, the more he rails against “the deep state” and “witch hunts,” the more they see him as a “truth-teller,” an outsider disrupting the status quo. That he openly curses and rambles incoherently is not a bug, it is the feature of his particular brand of populism.

After acquittal in his impeachment trial, Trump said: “We were treated unbelievably unfairly. You have to understand, we first went through ‘Russia, Russia, Russia.’ It was all bullshit” (Haltiwanger). Here is the vulgarity and repetition that is so potent. His lexicon and odd syntax may turn off prescriptive linguists, but that does not matter. A notorious “Trumpism” is “believe me,” which to the MAGA crowd, “is a sign of the common touch, of Trump using the same discourse markers that ordinary folk do in everyday speech” (Simms). When Trump shouts “We’re going to build the wall!” at a rally, he frames it as a collective action, evidence of active leadership. Just as his words are shorter, “his sentences are shorter and he uses fewer nouns compared with the number of verbs, and far fewer noun-noun combinations” (Hunston). Trump prefers imperative commands over declarative statements, and brevity over length. Using fewer nouns in proportion to verbs shows his desire to appear decisive and direct. When he delivers unscripted remarks, it is often a series of non-clause sentence fragments strung together. Transcripts of Trump interviews read like streams of consciousness. There is little flow to how he talks, and while it has been suggested he was a better speaker in the past, has either modified his speech or is dealing with the effects of age or dementia, that is another debate altogether. What is undeniable is that despite being wildly unconventional, Trump’s language has an impact. The question is to what extent.

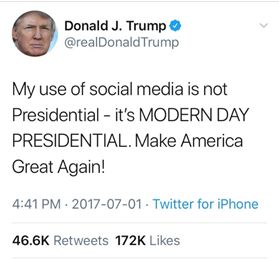

In justification of his Twitter use, Trump once tweeted: “My use of social media is not Presidential – it’s MODERN DAY PRESIDENTIAL” (@realDonaldTrump). In essence, Trump is a Twitter troll, and it could be argued that without social media, he would not be President. But Twitter simply reflects his spoken English, as using all caps is the equivalent of altering the pitch of his voice or changing his facial expression. For all his faults, Trump has always had a gift for marketing. Language is performative and transactional to him. It does not need to be factual, it only needs to serve the moment and his interests. Trump’s incessant repetition penetrates the minds of supporters and detractors alike, and the media is unwittingly complicit, “used as an amplifier for his falsehoods and frames” (Lakoff and Duran). George P. Lakoff and Gil Duran encourage the media to contextualize everything Trump says, and not carelessly repeat or show his lies. But this is easier said than done. Trump’s presidency seems like the embodiment of postmodernism, where nothing really matters, and anything goes. His potential to influence English is huge, but does he actually influence it in a meaningful way? Phrases like “fake news” and “alternative facts” are somewhat Orwellian, but they have not fundamentally changed English. Trump’s use of bigly and covfefe is well-known, but they have not become part of the vernacular. Perhaps the more important question is not if Trump influences English, but how we should respond to the toxic climate his language perpetuates.

Works Cited

@realDonaldTrump. “Despite the constant negative press covfefe.” Twitter, 31 May 2017, 12:06 a.m., Deleted tweet.

@realDonaldTrump. “My use of social media is not Presidential – it’s MODERN DAY PRESIDENTIAL. Make America Great Again!” Twitter, 1 July 2017, 4:41 p.m., https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/881281755017355264?lang=en. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Haltiwanger, John. “Trump called the Russia investigation ‘bullshit’ in rambling White House acquittal speech.” Business Insider, 6 Feb. 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-calls-russia-probe-bullshit-in-rambling-acquittal-speech-2020-2. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Hunston, Susan. “Donald Trump and the Language of Populism.” University of Birmingham, 2017, www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/perspective/donald-trump-language-of-populism.aspx. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Lakoff, George P., Gil Duran. “Trump has turned words into weapons. And he’s winning the linguistic war.” The Guardian, 13 Jun. 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jun/13/how-to-report-trump-media-manipulation-language. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” 1946, pp. 3-9. Public Library, http://www.public-library.uk/ebooks/72/30.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Simms, Karl. “One year of Trump: Linguistics expert analyses of U.S. President’s influence on language.” University of Liverpool, 19 Jan. 2018, https://news.liverpool.ac.uk/2018/01/19/one-year-trump-linguistics-expert-analyses-us-presidents-influence-language/. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Wamsley, Laurel. “The Covfefe Act Has A Silly Name – But It Addresses A Real Quandary.” NPR, 12 Jun. 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/12/532651827/the-covfefe-act-has-a-silly-name-but-it-addresses-a-real-quandary. Accessed 9 Mar. 2020.

Zeleny, Jeff, et al. “Trump’s ‘Fire and Fury’ Remark Was Improvised but Familiar.” CNN, 9 Aug. 2017, www.cnn.com/2017/08/09/politics/trump-fire-fury-improvise-north-korea/index.html. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Comments are closed.