Thursday, January 18th, 2018

The Rise of Middle English – with a little help from the French

April Anderson

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, the English language underwent a drastic change. It was at this time that the shift from Old English to Middle English began to occur. The Middle English period saw many new linguistic phenomena take hold around 1150, and continue to shape this new form of English until about 1500 (OED s.v. Middle English, n, sense A). However, there is evidence that the catalyst for these changes began in the years between 1066 and 1200 (Baugh and Cable 98), leading to phonological and lexical changes in the English language.

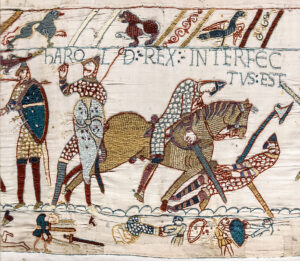

Figure 1. Bayeux Tapestry – Scene 57: the death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

After King Harold was killed during the Battle of Hastings in 1066 (see fig. 1), much of the English nobility was replaced by the Normans. This was because a majority of King Harold’s nobles had either been killed in battle or perceived as traitors, leaving many positions of authority available for the taking (Baugh and Cable 101). These positions were inevitably filled by the Norman nobility because they remained noblemen under the new king, William. Because they gradually took over these positions of power, the Normans gained more control in areas of legislation. Despite the presence of the French in these new governments, many of the new nobility did not live in England (Liu C.39). Due to their absence, many of the English-speaking citizens would not learn French right away.

Click here to read more