Interlocutory injunction and enforcement order granted. The defendants are restrained from preventing access to key service roads used by the plaintiff, Coastal GasLink Pipeline Ltd.

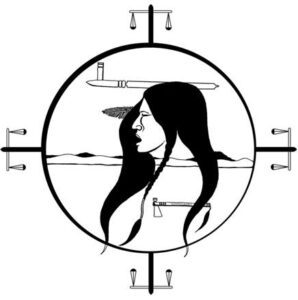

Indigenous Law Centre

Indigenous CaseWatch Blog

The plaintiff, Coastal GasLink Pipeline Ltd, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of TC Energy Corporation (formerly known as TransCanada Pipelines Ltd). The plaintiff obtained all of the necessary provincial permits and authorizations to commence construction of a natural gas pipeline [the “Pipeline Project”]. Over a period of several years beginning in 2012, the defendants set up the Bridge Blockade on the Morice West Forest Service Road [“FSR”]. The defendants have said publicly that one of the main purposes of the Bridge Blockade was to prevent industrial projects, including the Pipeline Project, from being constructed in Unist’ot’en traditional territories. In 2018, the Court granted an interim injunction enjoining the defendants from blockading the FSR. Blockading persisted, however, at another access point along the road, which resulted in the Court varying the interim injunction order to include all of the FSR.

The Pipeline Project is a major undertaking, which the plaintiff contends will generate benefits for contractors and employees of the plaintiff, First Nations along the pipeline route, local communities, and the Province of British Columbia. The defendants assert that the Wet’suwet’en people, as represented by their traditional governance structures, have not given permission to the plaintiff to enter their traditional unceded territories. The defendants assert that they were at all times acting in accordance with Wet’suwet’en law and with proper authority. The Wet’suwet’en people have both hereditary and Indian Act band council governance systems and there is dispute over the extent of their respective jurisdictions.

The Environmental Assessment Office issued to the plaintiff a Section 11 Order that identified the Aboriginal groups with whom the plaintiff and the Province of British Columbia were required to consult regarding the Pipeline Project. The plaintiff engaged in consultation with the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs through the Office of the Wet’suwet’en over a number of years. The Office of the Wet’suwet’en expressed opposition to the project on behalf of 12 of the 13 Wet’suwet’en Houses. Offers by the plaintiff to negotiate agreements with the Office of the Wet’suwet’en have not been accepted.

The plaintiff has entered into community and benefit agreements with all five Wet’suwet’en elected Bands. The long-term financial benefits to those, and 20 other Indigenous Bands, may exceed $338 million cumulatively over the life of the Pipeline Project. The elected Band councils assert that the reluctance of the Office of the Wet’suwet’en to enter into project agreements placed responsibility on the Band councils to negotiate agreements to ensure that the Wet’suwet’en people as a whole would receive benefits from Pipeline Project. This appears to have resulted in considerable tension between the Office of the Wet’suwet’en and the elected Band councils.

The Court found that the reconciliation of the common law with Indigenous legal perspectives is still in its infancy (Beaver v Hill, 2018 ONCA 816 [“Beaver”]). Indigenous customary laws generally do not become an effectual part of Canadian common law until there is some means or process by which they are recognized. This can be through its incorporation into treaties, court declarations, such as Aboriginal title or rights jurisprudence, or statutory provisions (Alderville First Nation v Canada, 2014 FC 747). There has been no process by which Wet’suwet’en customary laws have been recognized in this manner. The Aboriginal title claims of the Wet’suwet’en people have yet to be resolved either by negotiation or litigation. While Wet’suwet’en customary laws clearly exist on their own independent footing, they are not recognized as being an effectual part of Canadian law. Indigenous laws may, however, be admissible as fact evidence of the Indigenous legal perspective. It is for this purpose that evidence of Wet’suwet’en customary laws has been considered relevant in this case.

There is significant conflict amongst members of the Wet’suwet’en nation regarding construction of the Pipeline Project. The Unist’ot’en, the Wet’suwet’en Matrilineal Coalition, the Gidumt’en, the Sovereign Likhts’amisyu and the Tsayu Land Defenders all appear to operate outside the traditional governance structures of the Wet’suwet’en, although they each assert through various means their own authority to apply and enforce Indigenous laws and customs. It is difficult for the Court to reach any conclusions about the Indigenous legal perspective. Based on the evidence, the defendants are posing significant constitutional questions and asking this Court to decide those issues in the context of the injunction application with little or no factual matrix. This is not the venue for that analysis and those are issues that must be determined at trial.

The defendants have chosen to engage in illegal activities to voice their opposition to the Pipeline Project rather than to challenge it through legal means, which is not condoned. At its heart, the defendants’ argument is that the Province of British Columbia was not authorized to grant permits and authorizations to the plaintiff to construct the Pipeline Project on Wet’suwet’en traditional territory without the specific authorization from the hereditary chiefs. Rather than seeking accommodation of Wet’suwet’en legal perspectives, as suggested by their counsel, the defendants are seeking to exclude the application of British Columbia law within Wet’suwet’en territory, which is something that Canadian law will not entertain (Beaver).

Such “self-help” remedies are not condoned anywhere in Canadian law, and they undermine the rule of law. The Supreme Court of Canada has made it clear that such conduct amounts to a repudiation of the mutual obligation of Aboriginal groups and the Crown to consult in good faith (Behn v Moulton Contracting Ltd, 2013 SCC 261).

All three branches of the test for an interlocutory injunction are satisfied. Injunctive relief is an equitable remedy. In the Court’s view, it is just and equitable that an injunction order be granted and that this is an appropriate case to include enforcement provisions within the injunction order. The public needs to be informed of the consequences of non-compliance with an injunction order (West Fraser Mills v Members of Lax Kw’Alaams, 2004 BCSC 815).

Note: Benjamin Ralston is a sessional lecturer at the College of Law and a researcher at the Indigenous Law Centre. We are proud to acknowledge his contribution as co-counsel for the defendants in this case.