You’ve heard the term “micro” before. You’ve also likely heard the term “macro.” So what’s the difference? The textbook describes macroeconomics by asking questions that suggest a broader form of decision making. For example, questions ask about the availability of jobs in the entire economy, national employment rates, inflation (the general rise in prices), a country’s standard of living, economic growth, the money supply, and a whole lot more. Such questions pertain to the economy as a whole and often, how the government will make decisions to change outcomes at the national level and for the country as a whole.

This class will focus on microeconomics, which is the study of how individuals and firms make decisions. If you are in Ag-Biz, then you will likely see the connections and relevance to businesses right away. The textbook introduces the study of microeconomics by asking questions about: how individuals and firms spend money (allocate budgets), how to combine resources in a way to make money, what types of trade-offs people must make in their decision making, how much to produce, how much to purchase, how many workers to hire, etc. All these questions have to do with individuals and individual firms as opposed to governments.

While we will by studying microeconomics in this class, both forms of economic inquiry use theory and models to evaluate the world. A theory is an idea or set of ideas used to explain how things work. It is usually based on observations and facts and can be used to make predictions. The stronger the theory, the more times it will be correct when used to make such predictions. You should note that theories are simplified versions of reality. While you can usually always think of an example to refute the theory, in general, most of the time, the theory can be used to generalize something.

The study of microeconomics uses many theories to explain the behaviour of consumers and producers, societies, and governments for example. Some theories that we will investigate include production theory, which examines how firms make decisions to combine inputs in a way that produces the most valuable set of outputs. The theory of consumer choice examines consumers’ preferences and how consumers choose to spend their scarce budgets. When we put consumers and producers together and allow for the free exchange of goods, we get markets and can look at the theories of demand and supply, and how together they can be described using the invisible hand theory proposed by Adam Smith, who explains “by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” In other words, there is no single entity that controls production or consumption in the market, but by serving ourselves, we ultimately make the whole system work.

When we expand our investigation of agricultural production and consumption of food, feed, and bioproducts, we can look to trade theory to determine how prices and preferences affect global demand for domestic products and domestic demand for imports. We can also determine what happens in our markets when we open them for import: we can determine what that will do to prices and how much we consume. Additionally, we could examine how governments make decisions around policy looking at social choice theory and the theory of economic growth.

Some of these theories will be reviewed in this class, while others form the basis for higher-level economics classes that focus on investment and financial markets, transportation, marketing, production, trade, supply chains and supply management, agricultural policy, and even the environment. The key message is that theories are important because they provide a framework to help us think clearly about cause and effect and to allow us to test hypotheses to determine outcomes.

Economic models are also important to the study of economics. They are closely related to theories and can be mathematical, scientific, or even visual (think of a small model car – while it doesn’t work, it shows a smaller and simpler version of reality). The purpose of a model is to illustrate complex relationships and processes using a simple framework. Economics relies very much on mathematical models and graphical images to estimate the effects of changes in supply and demand, government policies, and change in international relations for example. Models are powerful tools that enable us to predict outcomes and to make choices based on such outcomes.

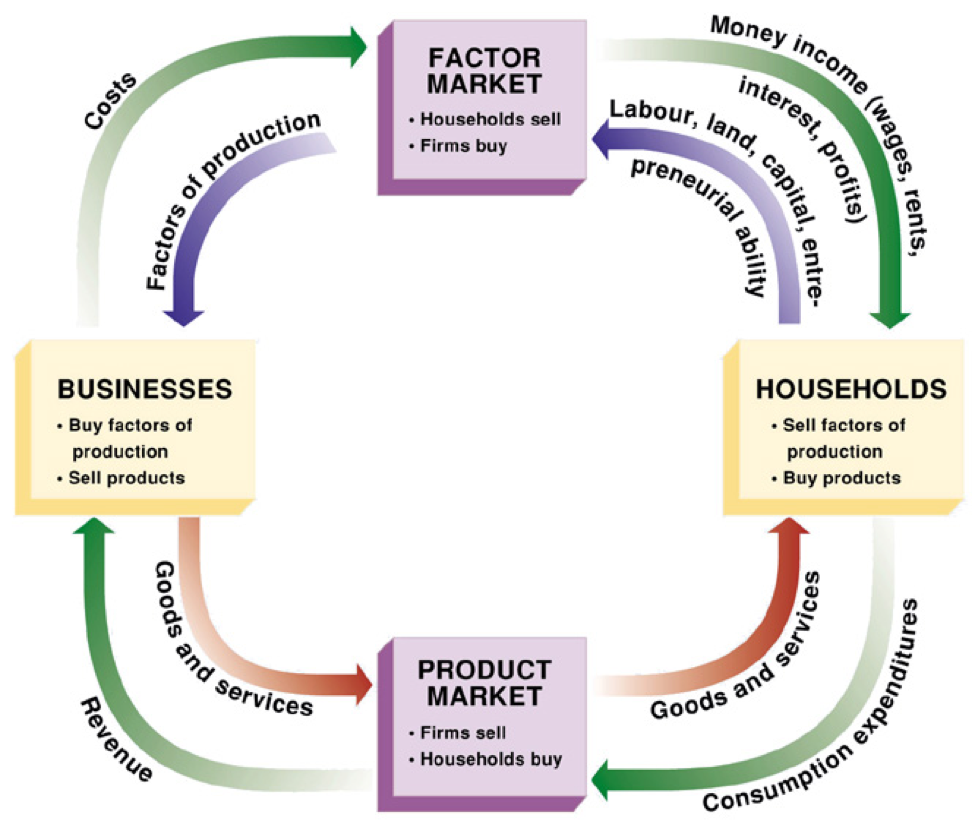

A model that is covered in the textbook is the circular flow diagram used to describe how an economy works between households and firms (Figure 1). You can see the flow of resources from one entity to the other, and the flow of goods and services. It’s possible to build on this diagram to include wastes and environmental effects, as well, and even energy uses and losses and leaks from the system.

The circular flow diagram below is a model of how economies work. Have you hear the term, “money makes the world go round?” Well, this is kind of the same idea. Money flows in one direction (clockwise in the diagram), and stuff, which could be products, labour, and inputs, for example, flows in the other direction (counter-clockwise).

The “money” arrows are green and the “stuff” arrows are purple. Let’s start by discussing the boxes. The box marked “Business” represents all businesses, manufacturers, farmers, etc.: any entity that is in business to make or grow and sell stuff to consumers. To make stuff, they need to shop in the “Factor Market” which represents the factors of production. They are like ingredients in the production process and include labour, raw materials (e.g. seeds, fertilizer, herbicides), capital equipment (e.g. tractors, buildings), land and even financial resources, and there is a market for each of these things.

Figure 2-1: Circular flow diagram. Source: http://wiki.ubc.ca/File:Circular_Flow_Simple.jpg. Permission: CC BY 4.0

Next, let’s look at the box marked “Households.” The box represents families, workers, and individuals. We need jobs to live and we, in fact, are a factor of production if we consider ourselves to be “labour.” Between these three boxes, we can see how the money flows. Businesses shop in the labour market to hire us to work. The money businesses spend to hire us is called “wages” otherwise known to us as “income.”

Businesses then use the factors of production to make products they sell in the product market (the box at the bottom of the diagram). We sell labour and other factors of production to firms that make products we want to buy. How do we pay? Of course, we use the money we earned from our labour. What we pay turns into revenue for firms to use to hire more factors of production. And so it goes.

If we wanted to add another layer to account for other aspects of our markets, we would have to add natural resources that both households and firms use. And, for both groups, there is an inevitable amount of waste that the entire system emits. The study of environmental economics focuses closely on these external factors and suggests that the system is not closed (as appears in our circle), but open with leaks and spill-overs. For a very good critique of the circular flow diagram visit Kate Raworth at Doughnut Economics. Remember that you have to understand something well before you can critique it thoughtfully.

Conduct an Internet search for images of the “circular flow diagram.” What other factors could be added to the model?

The point of the circular flow diagram is to show you a simple model of how the economy works. You can see right away that it certainly doesn’t explain our complex economies in great detail and that reality might not work exactly this way. However, this model helps us to frame some of the simpler ideas and allows us to then solve more complex problems and ask questions that need to be answered. This will be true of all models in this course – they are simple frameworks that give us a place to start.